Significance of Syria's Support for the Russian Invasion of Ukraine

Syria was one of only five countries that opposed the UN General Assembly (GA) resolution calling for an end to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Its vote was related to Russia’s support for the Syrian regime, without which it is unable to maintain control over Syrian territory. There also have been reports of recruiting Syrian fighters for a Russian operation in Ukraine. Thus, the Western pressure on Arab states not to return to full relations with the Syrian regime should become part of the efforts to isolate Russia.

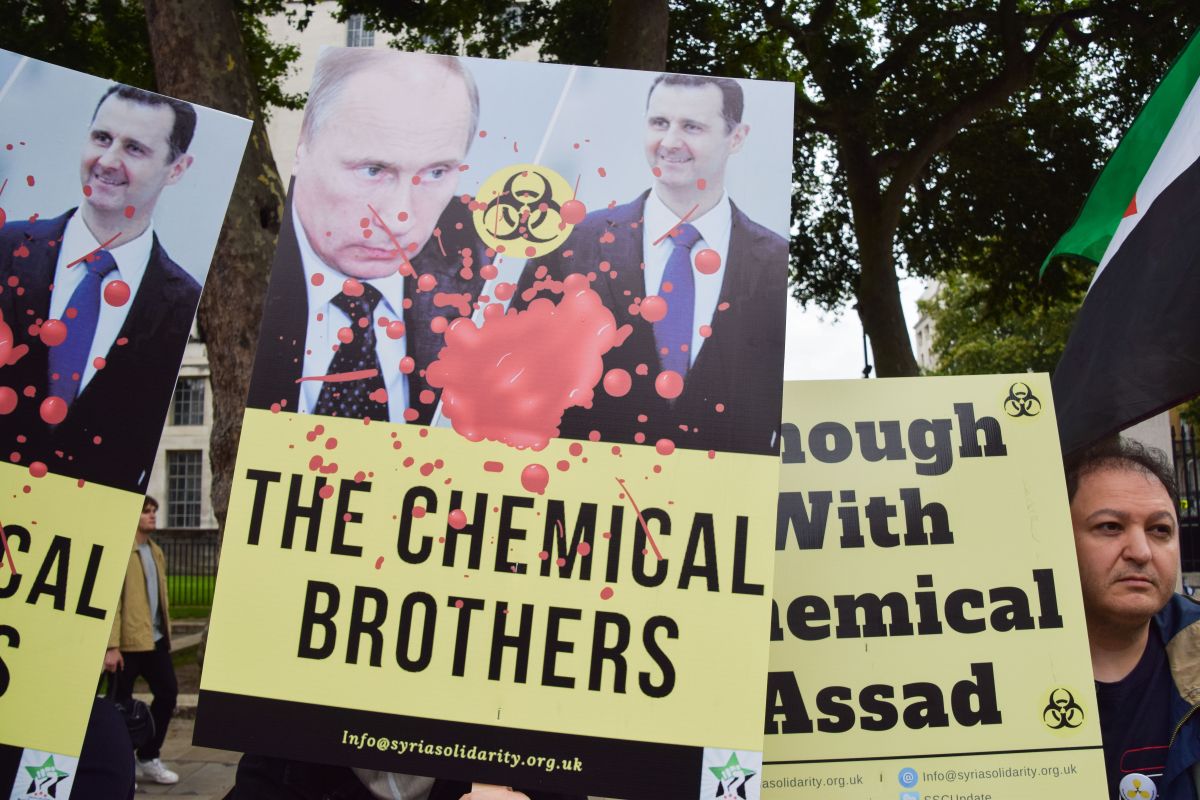

Vuk Valcic/ Zuma Press/ FORUM

Vuk Valcic/ Zuma Press/ FORUM

Motivations for Supporting Russia

Russia’s military intervention in the Syrian civil war allowed Bashar al-Assad to regain control of most of the territory, changing the dynamics of the conflict. This strengthened Russia’s influence in the Middle East and guaranteed the political support of Assad for it. Since the beginning of the conflict, the Russian authorities have criticised the support of the Syrian opposition by Western, Arab, and Turkish states as foreign interference aimed at a legitimate government. To maintain power in a country under international sanctions and destroyed after more than a decade of civil war in which opposition forces backed by other countries are involved, Assad must rely on his most important ally, Russia.

Before Russia’s military involvement, Syrian pro-government forces were losing territories to opposition groups and terrorist organisations. On an official request from Assad for support in the fight against rebel militias and terror groups, including ISIS, and increasing its territorial gains, the Russian authorities decided to become militarily involved in addition to financial and training aid. This allowed the government forces to regain control of around 70% of Syrian territory, including the six most important cities, including Damascus and Aleppo, and 12 million of the 17 million Syrians remaining in the country (around 7 million are outside Syria). Although from the beginning of the intervention Russia presented its support as combating Islamist militias and terrorist outfits, only a small part of its operations was directed against ISIS, and it did not join the international coalition to fight the terrorist organisation.

Opportunities and Risks

The Assad regime used the international debate on the war in Ukraine to improve its image among the Arab population by appealing to an anti-Western narrative. Syria’s UN representation presented its vote against the GA resolution as opposing Western hegemony and it criticised the UN for not using a similar method to oppose Israeli actions in Palestine or the violation of Syria’s sovereignty by the U.S. and Turkey. This is in line with the rhetoric of some Arab media, statements by the Syrian opposition, and some activists. Western states are accused of double standards in comparisons of their approach to the war in Ukraine to their lack of proper involvement in Syria or on the Palestinian side. Linking support for Russia with criticism of “Western imperialism and hegemony” also appeared in statements by Iranian officials and representatives of militants and organisations supported by Iran in Iraq and Lebanon. Assad also tried to emphasise the importance of Syria in Russian foreign policy, referring to the visit of Syrian Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad to Moscow three days before the invasion and claiming that Vladimir Putin had discussed the invasion with him two months before it began.

Assad is also counting on less Russian pressure for him to compromise during debates on the future of Syria within the UN. Russia recognised that the only way to full re-legitimacy of Assad’s power, and thus stabilisation, allowing for the commencement of investments and the reconstruction of the state, of which Russia would also be a beneficiary, was through the United Nations. That is why Russian policymakers had been criticising Assad’s intransigent approach to work on a new Syrian constitution, which blocked attempts at dialogue. Assad’s regime also opposed the vote passed in July last year in the UN Security Council regarding the mechanism to deliver humanitarian aid to Syria via Turkish territory. This mechanism, whose mandate expires in July this year, was deemed by the Syrian president as politicised, aiming to undermine the legitimacy of his regime.

Assad’s support for the Russian invasion and the convergence of his position with Russian propaganda will most likely induce greater pressure from Western states on Arab states to limit normalisation of relations with the Syrian regime. Although these states initially supported opposition groups, for several years they have been striving to normalise relations with Assad and reintegrate Syria into the Arab League (AL). In March, Assad visited the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on his first visit to an Arab state in 11 years. The decisive factor in the change of approach the Arab monarchies in the Persian Gulf (except Qatar) and others to the Assad regime was Russia’s involvement in the conflict. They concluded that Russia’s support for Assad would help to stabilise the situation in the country and limit Iran’s unfavourable influence in Syria. The invasion of Ukraine, however, may diminish Russia’s credibility as capable of ensuring stability in Syria. In the months leading up to the war, Russian military activity in violation of the U.S.-Russia deconfliction protocols from 2015 increased, and Russian and Syrian fighter jets conducted patrols near the border with Israel. In addition, a few days after the start of the invasion of Ukraine, Syrian government forces reached an agreement with Iranian paramilitary organisations to include their members in the ranks of the Assad regime. So far, the Russian authorities have opposed this, which also motivated the Arab states to move closer to the Assad regime.

Practical Aspects of Syrian Support

According to reports, Assad’s support for the Russian invasion may take the form of the direct participation of experienced Syrian pro-government fighters during the siege of Kyiv and urban fighting. Although the numbers provided by Russian sources are overstated (around 40,000), reliable local sources cited by the international and Arab press confirm the ongoing recruitment of Syrians to the fighting in Ukraine, including via the Wagner Group, a private military company. This resembles Russia’s tactics in other conflicts. Syrian fighters have already been recruited for fighting in Libya and the Central African Republic where UAE companies have participated in their arming and transport. Contrary to previous recruitments, this time Russia is only interested in fighters who have experience working with groups trained and supported by the Russian Federation.

In response, opposition groups supported by Turkey announced that their members would join the International Legion in Ukraine. Considering Turkey’s close relations with both Russia and Ukraine, however, the state will not support such an initiative.

Conclusions and Perspectives

From Assad’s point of view, the most important benefit from supporting the isolated Russia will be its actions in the forum of international organisations concerning Syria. Russia is likely to vote against the extension of the mechanism for providing Syria with foreign aid through Turkish territory, which may aggravate the humanitarian disaster in the country. This, in turn, will serve Assad’s criticism of Syria’s isolation by the West as being responsible for the deterioration of the living conditions of Syrians. The involvement of Syrian militants in Ukraine is likely to increase the level of brutality in the conflict and to intensify the anti-Islamist narrative used by some European right-wing groups. This could be used in Russian propaganda to further undermine the image of Western countries in Africa and the Middle East. It also will be important to exert pressure on the UAE to control companies potentially involved in supporting the smuggling of weapons and people into conflict zones and to impose international sanctions on them.

Only further coherence and an unprecedentedly harsh Western reaction to Russia’s actions can make the risks of Syria supporting Russia outweigh the potential benefits for Assad. The lack of a quick victory for Russia in Ukraine made the narrative in Arab media more critical of the Russian aggression, and Russia itself less trustworthy. This may increase the effectiveness of Western pressure on Arab leaders to suspend the normalisation of relations with Assad and the effort to return Syria to the AL. The biggest obstacle in this regard will be the UAE’s ever closer relationship with the Assad regime. The growing role of Iranian militias and the further economic weakness of Russia may discourage Arab leaders from making political rapprochement with Assad and from continuing to support investments, without which the reconstruction of the state will be impossible.

_sm.jpg)