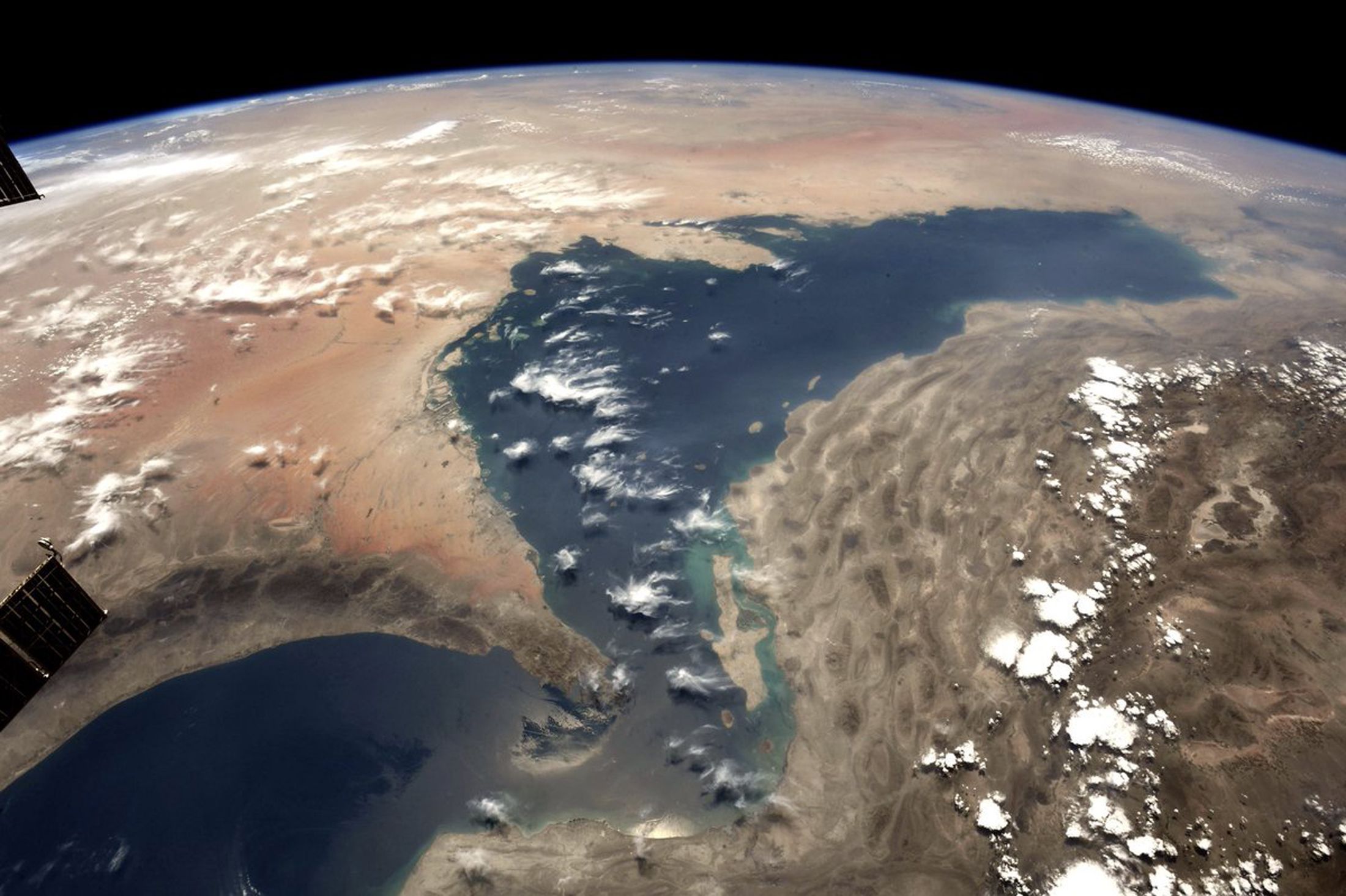

The Development of an EU Strategy for the Persian Gulf

The European Union’s policy towards the Persian Gulf, shaped primarily by the interests of the largest EU members, is inadequate to the challenges posed to the Union by the subregion and its growing importance in international relations. The Gulf states are becoming more and more actively involved in the affairs of the region, and their rivalries threaten the implementation of the EU’s neighbourhood policy. Developing a strategy and appointing a special representative for the Persian Gulf would enable the EU to pursue its interests in the subregion more effectively, including co-ensuring security with local actors.

While the Persian Gulf’s role in the Middle East is only increasing, the Union’s policy towards the subregion remains reactive. As a result, the EU lacks the ability to influence processes that directly affect its security. The Persian Gulf states, motivated by their interests in the Middle East, interfere in ongoing conflicts and exacerbate them, which not only adversely affects the stability of this part of the world but also limits the potential for the development of economic relations between the EU and its immediate neighbourhood. As well it leads to enhanced people and weapons smuggling networks. An EU strategy and envoy for the Persian Gulf would better address these phenomena and counteract problems “at their source”.

The development and adoption of such a strategy would also be a logical step in relation to the evolution of EU policy towards the subregion where it seeks to strengthen political cooperation with its countries in order to establish itself as a key partner. This is evidenced by the first political dialogue between the EU and Iraq, which took place under a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement in January 2020, or talks in the “E3+” format (UK, France, Germany plus Italy and Iran). The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) remains the only institutionalised tool of multilateral cooperation in the subregion. Although the 1988 and 2010 agreements between the EU and the GCC provide for strengthening cooperation at the multilateral level, the 2019 document on deepening political dialogue, cooperation, and promoting contacts between the EU and the GCC deals mainly with bilateral relations with the GCC countries. The advantage of bilateral relations is also demonstrated by the EU representations in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Kuwait that represent just the Union in relations with individual members of the Council.

The EU and the Growing Importance of the Gulf States

The “Arab Spring”’ increased the importance of the Gulf states for regional security and the European Union itself. The leaders of Arab monarchies regarded the demonstrations as a threat to the sustainability of their power, and the Iranian authorities saw them as a threat to its position in the region. These leaders started to defend their interests more assertively, interfering in regional conflicts and the internal affairs of Middle East and North African countries, which deepened regional destabilisation. For example, Saudi Arabia and the UAE supported the coup in Egypt in 2013 that led to the overthrow of the first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi. Both countries also engaged in the war in Libya on the side of Gen Khalifa Haftar (who was also supported by France), while Qatar and Turkey supported the other side, the government of Fayez al-Sarraj. Further destabilisation shifted the centre of Euro-Middle Eastern relations away from Syria and Egypt, traditionally central to Western states’ policy towards the Persian Gulf.

The revolution in Syria has particularly proved how harmful the EU’s reactive policy has been. The EU failed to develop an approach to the conflict that would ensure its resolution, which created space for regional power interests to play out. Ultimately, this led to an increased role for Iran and Russia in the Middle East, thanks to their support for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, as they were crucial for maintaining his power. Russia’s role in particular made ending the conflict in Syria impossible without considering its interests, which include keeping Assad in power. This has raised a serious dilemma in EU policy towards Syria and, more broadly, for the Union’s status as a normative power. On the one hand, the EU finds it difficult to ignore the reality of the survival of the Syrian regime, but on the other, it cannot fully accept the authority of a president who has committed war crimes and crimes against humanity. Iran’s involvement also influenced Saudi Arabia’s decision to support the rebels fighting against Assad. Currently, the Arab leaders of the Persian Gulf (except the Emir of Qatar), due to their hostility towards Iran and war-committed Turkey, are striving to normalise relations with the Syrian regime, which threatens the effectiveness of the EU efforts to isolate Assad. The worsening conflict led to the migration-management crisis that deepened divisions within the EU and in practical terms forced the signing of an agreement with Turkey in 2016. Pursuant to the agreement, the EU was to transfer €6 billion to Turkey in exchange for it accepting irregular immigrants from the EU. As a result, Turkey gained a significant instrument of pressure on the EU, which it has used to destabilise its policy.

Also, at that same time, Iranian-backed Shi'ite militias in Yemen, Lebanon, and Iraq were growing, deepening internal conflicts in those countries. Lebanese and Iraqi fighters supported Iranian troops in Syria. The aim of counteracting Iranian influence resulted in the military involvement of Saudi Arabia and the UAE in the civil war in Yemen since 2015. Saudi Arabia’s military intervention led to escalation and the death of most of the 15,000 civilian victims of the conflict. In this context, the EU succeeded in the creation of the only platform for dialogue on Yemen with the participation of Iran (the “E3+” with Italy and Iran), which helped to gain Iranian support for the creation of a UN special envoy for Yemen. The rivalry with Iran also influenced the groundbreaking decision of the rulers of the UAE and Bahrain to normalise relations with Israel, which indicated a re-evaluation of the Palestinian issue in the politics of these countries.

Since the beginning of the second decade of the 21st century, the Persian Gulf states have also been an increasingly important source in the EU’s quest for diversified energy supplies. In 2010, oil imported from Saudi Arabia and Iraq accounted for 3.3% and 1.9%, respectively, of all imports; by 2019, these percentages were 6.2% and 4.5% (according to Eurostat data). The EU is also increasing the volume of imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) as an alternative to the use of gas pipelines from Russia and high-emission oil and coal. The amount of LNG imported to the EU increased from 52 bcm per year in 2013 to around 72 bcm in 2020, and Qatar remains the largest supplier to the EU (41% of LNG was imported from that country in 2017). The EU’s interests in becoming independent of energy imports from Russia also influenced its efforts to reach a nuclear agreement with Iran. The EU contributed to the signing of the JCPOA agreement in 2015, which was the basis for establishing economic and political cooperation with Iran. It allowed for the development of trade: in 2017, EU imports from Iran increased by 83.9% and exports by 31.5% compared to the previous year. After the U.S. withdrew from the agreement in 2018, the EU created a special purpose company, INSTEX, to limit the impact of the renewed American sanctions on trade between EU countries and Iran.

Threats to EU Interests in the Region

While EU trade and investments in the Persian Gulf are growing, their potential is limited by the lack of reform in the Gulf states. The need for changes results from the states’ exposure to the effects of climate change, economic dependence on energy resources, the dominant role of the state in the labour market (in 2016, about 65% of citizens were employed in the public sector in the GCC), widespread corruption and nepotism, and a dynamically growing population. According to the national strategies published in recent years (e.g., the Saudi “Vision 2030” or the UAE “Centennial 2071”), the Gulf States strive to transform their economies by investing in innovation and new technologies. They also facilitate investments by foreign institutions through tax breaks or the possibility of 100% foreign ownership in selected sectors. In the last decade, China has emerged as the most important economic partner of the Gulf states. Their relationship is centred on China’s growing energy demand and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) announced in 2013. For example, since 2014, between 70% and 80% of Oman’s annual oil exports have been to China. In 2019, the value of Chinese crude oil imports from Saudi Arabia increased by 47% compared to 2018. In the same year, the Chinese Silk Road Fund bought 49% of the shares in the renewable energy branch of Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power. Therefore, China is increasingly competing economically in the Gulf states with the EU, and its investments, which are not conditioned by criteria related to respecting democracy and human rights, contribute to the consolidation of authoritarianism and clientelism in the region.

The loss of EU competitiveness in relation to China is aggravated by fragmentation in Union relations with the Gulf states. The strongest Member States strive to maintain privileged relations with the Arab monarchies, influencing the perception by these rulers of their contact with the EU through cooperation with its individual members. For example, France’s relations with the GCC countries define the strategic importance of the arms industry for the French economy (in 2018, arms exports accounted for 1.8% of the value of all French exports). Despite the controversy over Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s intervention in Yemen, both countries remain among the largest recipients of French arms (second and fifth, respectively). Other EU countries remain critical of arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which influenced the decision of Germany, Sweden, and Italy to stop that trade in 2019.

The rivalry within the Gulf and the political goals of the subregion’s leaders contribute to the destabilisation and strengthening of authoritarianism in the Middle East. This threatens not only the EU’s plans to make the neighbourhood a zone of peace, prosperity, and stability, but also its economic interests. The Iran-Arab states dispute translates into insecurity on trade routes (from May to June 2019, Iran attacked six ships in the Persian Gulf), and Iran’s support for paramilitary organisations alone exposes it to sanctions that hinder the development of economic relations. The reactive nature of EU policy towards these phenomena threatens the effectiveness of European initiatives related to stopping arms smuggling, irregular migration, and the de-escalation of conflicts. For example, the UAE’s desire to limit Turkish influence in Libya made it impossible to achieve the goals of the European IRINI mission (the annual cost was around €10 billion), which was established to support the implementation of the UN embargo on arms supplies to Libya. From April 2019 to June 2020, about 6,200 tonnes of weapons and ammunition were imported into Libya from Emirates bases, and by April 2020, the UAE carried out more than 850 attacks in Libya using drones and aviation. Due to the destabilisation of Libya, smuggling networks developed there, which contributed to the record number of irregular immigrants (more than 181,000 people) arriving in Italy in 2016 through the so-called Central-Mediterranean route, which exposed the EU to further costs related to preventing irregular migration. The EU provided €5 million to and conducted training for the Libyan coast guard. In the financial perspective for 2021-2027, the European Commission approved a twofold increase in spending on counteracting irregular migration (from €13 billion to around €26 billion). However, the ongoing political and economic crises in Iraq and Lebanon, exacerbated by disputes between parties supporting Iran and those favourable to Saudi Arabia, make it difficult to combat the causes of migration.

The EU Strategy for the Persian Gulf—Conclusions

The development of the EU’s Persian Gulf strategy would help strengthen the Union’s position in the subregion. The EU Strategy for Central Asia could serve as a model. Any strategy would have to define the possibilities to prevent negative consequences for EU security resulting from Saudi-Iranian or Emirate-Turkish rivalries and the involvement of Gulf states in internal and regional conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa. It should criticise the influence of Arab monarchies in strengthening authoritarianism in the region as that threatens the EU’s goals, and it should define the possibilities of counteracting the increasing influence of China and Russia in the Middle East. It could do so, for example, through a more established political position in the Gulf, close relations with the U.S., and by strengthening support for the fight against terrorist organisations, including ISIS.

Addressing non-security challenges would allow the creation of a technical cooperation platform involving all countries in the subregion. The EU could take advantage of opportunities to reform the economies and labour markets of the Gulf states and their vulnerability to the effects of climate change. The EU, which has experience in strengthening state institutions and developing technologies related to renewable energy and innovation, could be an important partner for them and support the process of introducing reforms to make them independent of the export of raw materials.

EU cooperation with the Gulf states for the reconstruction of Iraq also would be beneficial. Support for European investments in the Gulf states would increase the importance of the EU as an economic partner, bearing in mind the need to reduce the role of Gulf state institutions in labour markets. At the same time, to strengthen cohesion within the EU, it would be beneficial to include in the strategy the interests of smaller Member States in order to counterbalance the strongest members’ abuse of their position in the subregion. Making EU policy towards the subregion more common would also strengthen its position in relation to the increasingly stronger China.

Implementation of the strategy would be supported by the appointment of a special envoy for the Persian Gulf whose task would be to maintain the EU’s image as neutral in the disputes between Iran and Saudi Arabia by supporting mediation between these countries. The EU’s potential in this regard is indicated by the success of the “E3+” format with Italy and Iran. An additional goal would be to react to the growth of tensions or actions in Arab states’ disputes with Iran and Turkey, which pose a direct threat to EU interests by leading, for example, to increased migration or threatening regional cooperation on gas trade. The Union also could take a leading role in discussions on anti-corruption reforms and climate policy in the subregion, as well as to provide support to European companies interested in investing in the Gulf, especially from EU countries that have less experience in the subregion.