Short-Lived Martial Law Deepens South Korea's Political Crisis

President Yoon Suk-yeol’s declaration of martial law on 3-4 December has triggered the most serious crisis in the democratic history of the Republic of Korea. Although in place only briefly, its overturning and the beginning of impeachment proceedings by parliament on 14 December means that the president has been suspended of his powers and the case referred to the Constitutional Court, which is expected to proceed on Yoon’s removal from office within six months. The difficult political situation will temporarily limit South Korea’s ability to act internationally, including establishing direct contacts with the incoming U.S. administration.

.png) Kim Soo-hyeon / Reuters / Forum

Kim Soo-hyeon / Reuters / Forum

From Martial Law to Impeachment

On the evening of 3 December, President Yoon announced the imposition of martial law in South Korea. He justified it by the need to break the paralysis of the state caused by the activities of the opposition, which he described as “pro-North Korean anti-state forces”. The martial law decree included a prohibition of all political activity, including actions of the 300-member National Assembly (parliament), local councils and political parties, and restrictions on press freedom. Some 1,500 soldiers were mobilised to arrest political party leaders, seize parliament, and copy data from the servers of the National Election Commission (NEC). Martial law was lifted on the morning of 4 December (it lasted for just six hours) after parliament rejected it under Article 77 of the constitution by the votes of the 190 MPs who managed to reach the session.

On the same day, the opposition, led by the liberal Democratic Party (DP), submitted a motion to impeach the head of state. According to Article 65 of the constitution, this requires the support of two-thirds of the total number of members of parliament (200 MPs). As the opposition has 192 seats in parliament, the motion also needed the support of at least eight lawmakers from the ruling conservative People’s Power Party (PPP). An attempt to vote on the motion on 7 December failed due to a lack of quorum (five MPs short of the required 200), as the PPP boycotted the vote. Its leader, Han Dong-hoon, and Prime Minister Han Duck-soo proposed that the president resign voluntarily and that they both take over the management of state affairs. Yoon refused to step down, and in the meantime the prosecution launched a criminal case against him for treason in connection with the imposition of martial law. Yoon’s intransigence and the public mood (mass protests and opinion polls showing around 75% of respondents wanted the removal of the head of state) meant that on 14 December the full parliament voted 204 to 85 in favour of the impeachment motion (three MPs abstained and eight invalid votes were also cast), meaning that it was supported by 12 conservatives.

Reasons for the Imposition and Failure of Martial Law

The order to arrest party leaders and send soldiers to the NEC suggested that the president's main objective was to crack down on political opponents, including challenging the outcome of the April parliamentary elections, in which the opposition strengthened its position and made it difficult for Yoon to govern. It rejected a number of bills, including the budget, called for the dismissal of more ministers and presidential advisers, and sought the prosecution of his wife, who has been implicated in numerous corruption scandals. Yoon’s approval ratings have been falling—from less than 20% before martial law was declared to 11% now—and more allegations have been made against him. These include the rigging of the 2021 intra-party elections that made him the PPP’s presidential candidate, and increasing presidential control over the prosecution, which was used to crack down on the opposition.

The threat from North Korea highlighted by the president was intended to justify the imposition of martial law. Media and opposition MPs, citing intelligence leaks, suggested that the Yoon administration was trying to provoke an escalation of tensions with North Korea in order to create a pretext for imposing martial law. This was supposedly facilitated by, among other things, the deployment of drones over Pyongyang in October, which was to be decided by Defence Minister Kim Yong-hyun, seen as the main architect of the martial law decree.

The failure of Yoon and his inner circle to enforce martial law was determined both by the immediate reactions of MPs and inept implementation resulting from the military’s opposition to the use of force. The details of the preparations and the imposition of the state will be determined by investigations by the police and prosecution and parliamentary inquiries, already launched. Testimony so far suggests that the decision was taken among the president’s most trusted associates, such as the ministers of defence and interior, and the commanders of defence counter-intelligence, defence security agency, and the defence of the capital. The turn of events suggests that the plan of the president and the defence minister did not have the approval of the entire army.

The Dispute over Yoon’s Impeachment

The Liberals wanted to impeach Yoon not only to remove him from office but also to strengthen their political position at the expense of the PPP ahead of possible early presidential elections. The favourite in the polls is DP leader Lee Jae-myung, who is polling at around 50% (second-placed Han Dong-hoon has around 10%).

The PPP boycotted the first vote on the impeachment motion, fearing a repeat of 2016. Back then, the conservatives supported an opposition motion to impeach President Park Geun-hye (over allegations of corruption and abuse of power) and subsequently lost power in the 2017 presidential election. In countering the opposition motion, the PPP sought to present itself as a force of stability and to persuade Yoon to resign. The conservatives hope that a verdict in one of Lee Jae-myung’s criminal cases (including corruption) will become final in the coming months, which would disqualify him from running in the early presidential election. In November, he was given a non-final sentence of one year in prison, suspended for two years, for making false statements during the 2021 presidential campaign.

Following the vote on the impeachment motion, the president was suspended from his duties, which were taken over by the prime minister. The case has been referred to the Constitutional Court, which has six months to rule. The impeachment of the president requires the support of at least six judges (there are nine judges on the court). Given there are three vacancies in the court, parliament intends to submit nominations for judges by the end of the year so that the case can be undertaken by a full court due to its political importance. The nominations require the approval of the incumbent president, which could lead to political disputes. If the court decides to remove Yoon from office, presidential elections must be held within 60 days.

Conclusions and Perspectives

Yoon’s declaration of martial law and its aftermath have triggered the most serious political crisis since South Korea’s democratisation in the late 1980s. The president’s decision, the first of its kind in the country’s democratic history, shocked the public because of its association with the authoritarian period when the military used the North Korean threat as a pretext for de facto coups and mass repression. There will be investigations of the imposition of martial law, accompanied by criminal trials, including on charges of insurrection against key figures in the state, including Yoon.

The lack of a bipartisan agreement on how to remove the president has exacerbated the political chaos. The ruling party and the opposition are preparing for a possible early presidential election, which is likely to intensify the political struggle. The mass public protests that put pressure on the Constitutional Court and are likely to work in favour of the liberals could be very important for the development of the situation. A possible criminal conviction of the opposition leader could aggravate the internal conflict.

On the one hand, the imposition of martial law and the ensuing political crisis are a serious blow to South Korea, which for almost 40 years had been consolidating its international image as a stable and democratic state. On the other hand, the swift rejection of martial law by the parliament and the mass protests demonstrate the resilience of democratic institutions and the strength of South Korean civil society.

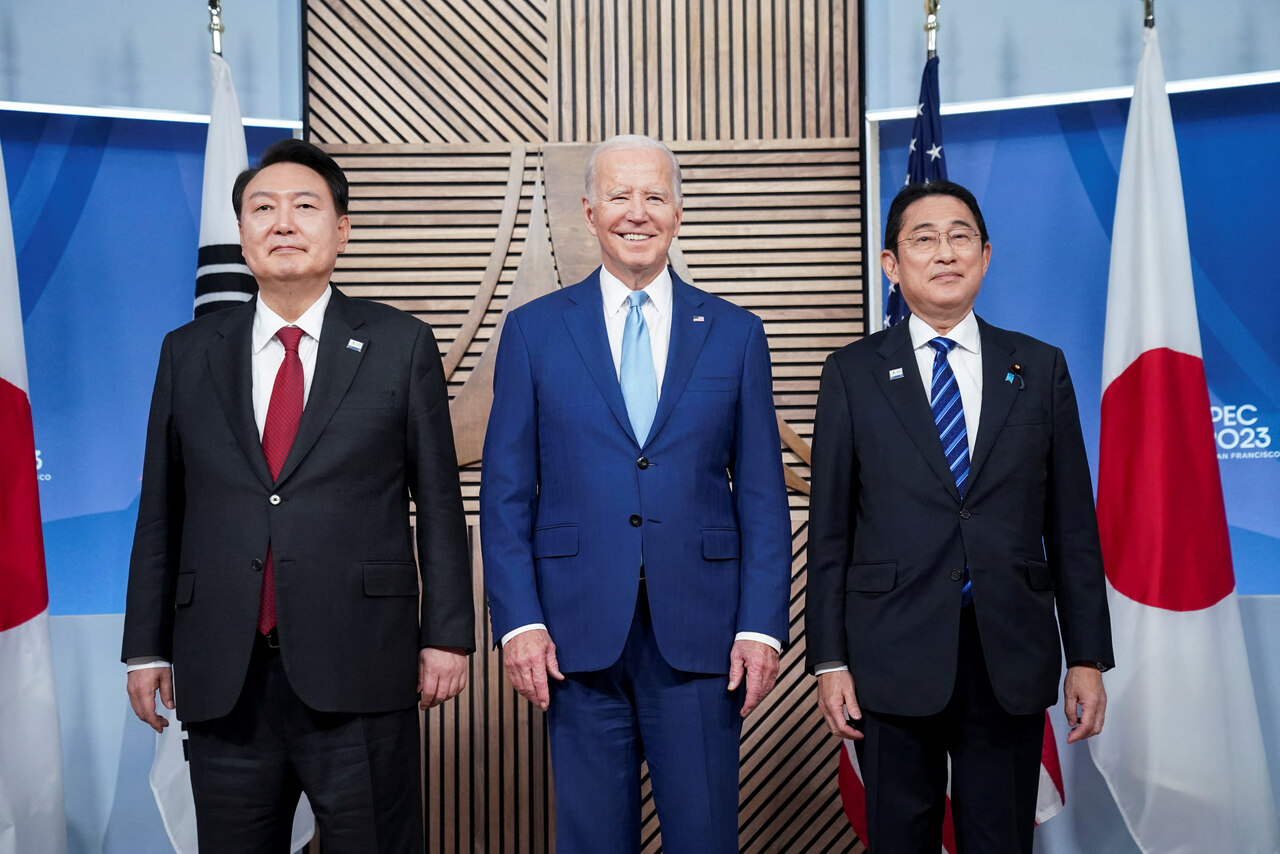

Yoon’s authoritarian tendencies undermine the credibility of his foreign policy based on the promotion of freedom and democracy and negatively affect the assessment of his achievements, such as the improving relations with Japan, strengthening trilateral cooperation with the U.S. and Japan, and deepening dialogue with NATO. The prime minister’s assumption of the presidency may temporarily limit South Korea’s international activities, including making it more difficult to establish direct contacts with the incoming Donald Trump administration.

A victory by a liberal candidate in the snap presidential election could lead to significant changes in South Korea's foreign policy. These could include abandoning a conciliatory stance towards Japan, siding less clearly with the U.S. in its rivalry with China, opposing military support for Ukraine, and weakening political dialogue with NATO. Regardless of the change of government, it will be in South Korea’s interest to continue cooperation with Poland in the defence dimension, seen through the prism of benefits to the South Korean arms industry.