Inter-Korean Tensions Increase

Inter-Korean relations have deteriorated significantly over the past year. The Republic of Korea and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea have been pursuing an openly hostile policy towards each other. In addition to confrontational rhetoric, they have been expanding military capabilities and developing cooperation with allies and partners (South Korea with the U.S. and Japan, North Korea with Russia and China). Potential destabilisation on the Korean peninsula would be unfavourable for Poland, as it could, among other things, induce the U.S. to become more involved in East Asia at the expense of Eastern Europe.

Rok Army / Zuma Press / Forum

Rok Army / Zuma Press / Forum

South Korea’s Stance

Since taking power in May 2022, President Yoon Suk-yeol has maintained a hardline stance towards North Korea, typical of the conservative camp. In August 2022, he admittedly expressed his willingness to support the North Korean economy and society, but on the condition of the prior denuclearisation of North Korea. In the National Security Strategy published in June 2023, the South recognised the North—for the first time since 2016—as a “major enemy”. Compared to the Moon Jae-in government’s (2017-2022) conciliatory policy towards North Korea, the Yoon administration has increased the emphasis on the problem of human rights violations in North Korea. Some officials, such as the unification minister, suggest that the only solution to the problems on the Korean peninsula would be the fall of the totalitarian regime in the North. The government in Seoul also accuses the authorities in Pyongyang of illegally using (i.e., without South Korean consent) factories in the Kaesong inter-Korean complex, which has not been operational since 2016.

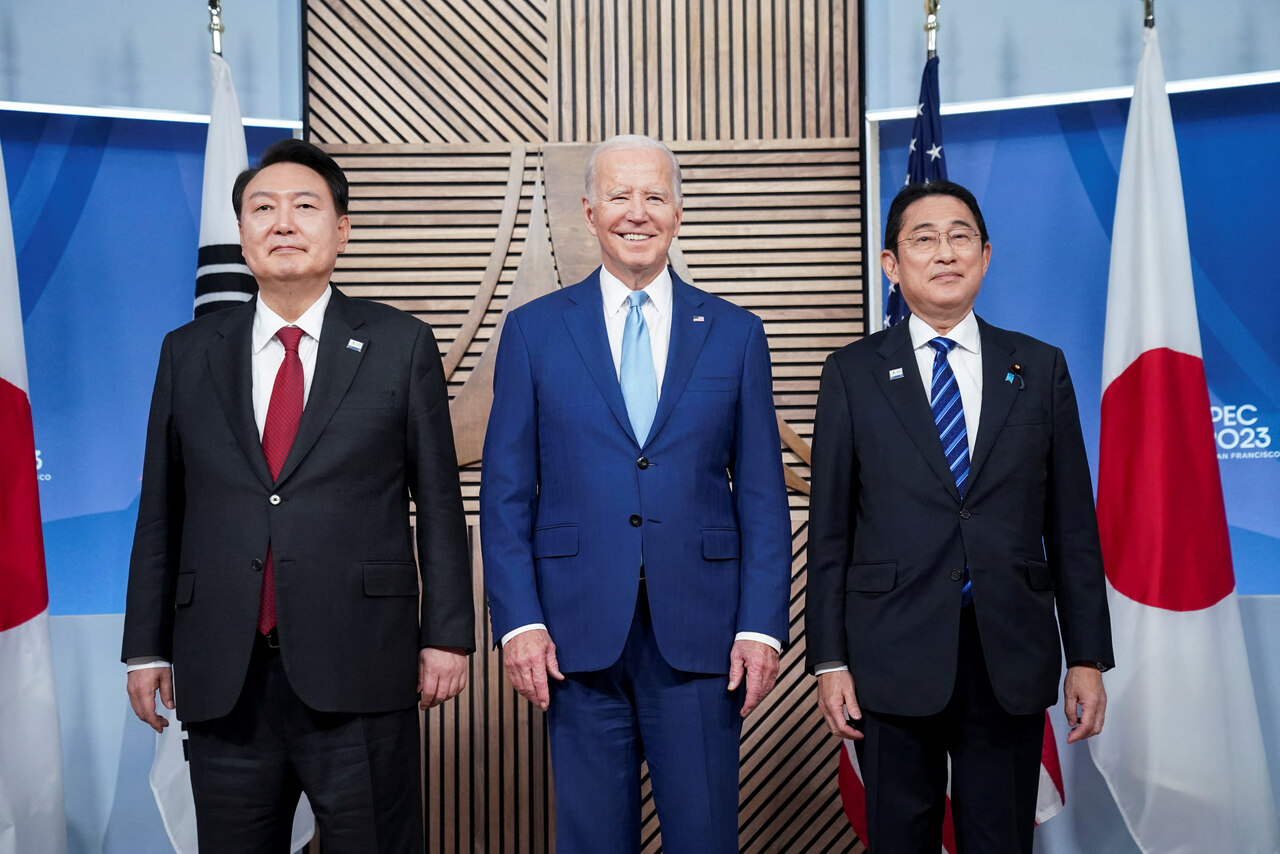

In response to the development of North Korea’s missile and nuclear forces, South Korea is strengthening its defence and deterrence capabilities. On the one hand, it has been developing its military capabilities for deterring or repelling a North Korean attack and carrying out severe retaliation. To this end, South Korea has been expanding its missile defence and offensive missile arsenal and enhancing its reconnaissance capabilities (last December, it launched its first military spy satellite). On the other hand, it has been intensifying defence cooperation with the U.S., as demonstrated by the increased intensity and scale of drills and the expansion of consultation mechanisms on nuclear deterrence. It has also been developing trilateral cooperation with the U.S. and Japan, mainly in detecting and responding to missile threats from North Korea.

North Korea’s Attitude

In response to the Yoon government’s tougher stance, North Korea has stepped up its rhetoric towards its neighbour. After months of tensions, last November, North Korea broke the 2018 agreement on confidence- and security-building measures on the inter-Korean border (a few weeks earlier, South Korea suspended part of the deal). On 30 December, during a party plenum, Kim Jong Un rejected the stated goal (since 1972) of Korean unification through dialogue with the South and described inter-Korean relations as a “relationship between two hostile countries”. He also announced the dismantling of institutions responsible for relations with the South and indicated the need to prepare military capabilities to “subjugate” South Korea in the event of a possible conflict. During a session of parliament on 16 January, Kim announced amendments to the constitution. It deletes articles on reunification, reconciliation, and Korean national unity, which are to be replaced by provisions describing the Republic of Korea as the North’s “principal enemy”. These steps represent an escalation of North Korea’s already hostile actions towards the Moon administration.

North Korea has been expanding its missile and nuclear capabilities with a view to their possible use not only against the U.S. but also against South Korea. Last August, it tested short-range missiles capable of carrying tactical nuclear payloads, and in November, it launched its first military spy satellite. Following the rupture of the 2018 agreement, it expanded border posts and intensified military exercises. In early January this year, it conducted artillery shelling of the disputed maritime border with South Korea near the Yeonpyeong and Baengnyeong islands. In an immediate response, the South shelled the North Korean side.

South Korea’s increased cooperation with the U.S. is one of the factors prompting North Korea to deepen its relations with Russia and China. According to the U.S., the U.K., and Ukrainian governments, North Korea is not only supplying Russia with artillery ammunition but also missiles such as the KN-23, which were to be used against Ukraine in late December/early January. In return, North Korea is to obtain military technology from Russia, including space technology, political backing in the UN Security Council, and support in circumventing sanctions. China, in turn, is a guarantor of North Korea’s economic survival. In 2023, trade between them increased to $2.3 billion, approaching its pre-pandemic value ($2.8 billion in 2019).

Conclusions and Perspectives

Further tensions between the Korean states will likely mark the coming year. North Korea’s departure from its decades-old policy of reunification may mean that inter-Korean relations will also be marked by confrontation in the long term, regardless of the political option forming the South Korean government. North Korea’s unequivocal break with the idea of dialogue will make it difficult for the South Korean liberals to resume talks should they take power in the next few years (the critical presidential election will take place in 2027). Taking an aggressive line towards the South is also part of the process initiated by the North during the pandemic to combat external influences, such as South Korean pop culture, in society.

Despite Kim’s declared readiness for military action, a full-scale conflict triggered by North Korea is unlikely due to the superiority of South Korean and U.S. forces. However, the breakdown of the 2018 agreement increases the likelihood of incidents or border clashes. The South (in cooperation with the U.S.) and the North will increase the intensity and scale of military exercises and build up military capabilities, especially missiles. More escalation could occur in the spring with South Korea’s annual drills with the U.S. (in March) and parliamentary elections in South Korea (in April). It is also possible that North Korea will increase the frequency of cyberattacks and secret service activity in South Korea, aimed at, among other things, stealing funds and military operational plans.

North Korea may be escalating tensions analogous to the situation in 2017 when this strengthened its negotiating position before talks with the Trump administration. Tensions on the Korean Peninsula may become one of the most important foreign topics in the U.S. presidential campaign. If Donald Trump wins this year’s presidential election, North Korea may prepare to return to talks with the new U.S. administration. However, it is doubtful that negotiations would involve denuclearisation, as talks on this subject failed in 2019 and North Korea has since expanded its arsenal. Kim could reopen dialogue with Trump to weaken the U.S. alliance with South Korea and strengthen his position in relations with China and Russia, which is one of the main goals of North Korea’s foreign policy. The North not only is helping to rearm Russia but also draws the attention of the U.S. and South Korea to itself, which is beneficial for Russia in terms of its aggression against Ukraine. North Korean activity may also complicate U.S. defence assumptions in East Asia, forcing U.S. planners to consider the prospect of simultaneous military action in two different locations, for example, in the Taiwan Strait and on the Korean Peninsula, including the potential for limited use of nuclear weapons. Even if these actions are not coordinated by China and North Korea, they would pose operational challenges for the U.S. and its allies.

Responding to threats from North Korea will test the credibility of South Korea’s alliance with the U.S. The allies will also strengthen their trilateral cooperation with Japan. South Korea will use its 2024-2025 non-permanent membership of the UNSC to raise the issue of North Korea’s actions to try to persuade other states to exert political pressure on it and implement UN sanctions and possible unilateral restrictions.

Destabilisation on the Korean Peninsula could also challenge European countries, including Poland. The escalation of tensions may prompt the U.S. to direct more resources and political attention to East Asia at the expense of Eastern Europe. In an extreme scenario, regular clashes between the Korean states could threaten shipping routes and disrupt supply chains, hindering the transport of military equipment, automotive battery components, and electronics from South Korea to Poland. It is in Poland’s interest to strengthen the dialogue with the Republic of Korea and Japan, also in the framework of their cooperation with NATO, to learn their assessments of the threats in East Asia and urge them to maintain their support for Ukraine.

.jpg)

.jpg)