Prospects for ISIS in Afghanistan

The ISIS faction Khorasan Province, ISIS-K, is using Afghanistan’s internal destabilisation to grow its structures in the region. It will mobilise supporters from neighbouring countries to challenge the strength of the Taliban and their ally Al-Qaida. ISIS-K is much weaker than them but aspires for a greater role through the escalating use of violence. By controlling part of Afghanistan, ISIS-K intends to build structures like those in Syria and Iraq in 2013-2019. The success of these plans would further threaten the security of the countries of Central and South Asia and increase the terrorist threat to Europe.

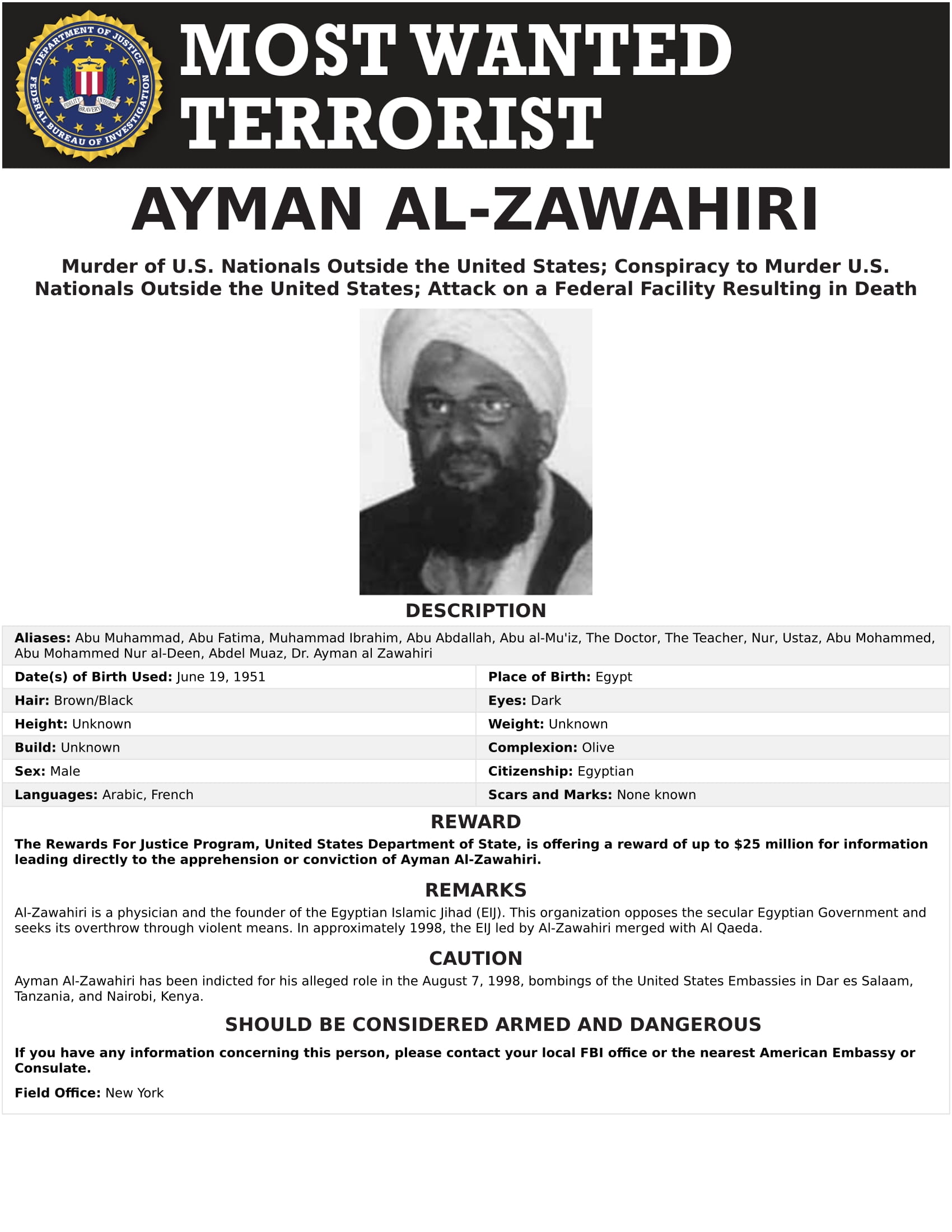

Photo: Wana News Agency/Reuters

Photo: Wana News Agency/Reuters

Conditions

Since the 1980s and the jihad against the Soviets, Afghanistan has remained a country invariably attractive to Islamic extremists. These ties were strengthened as a result of Afghan and people from neighbouring countries fighting in Iraq and Syria in 2014-2019 on the side ISIS. In the past, the scale of terrorist groups’ activity in Afghanistan was dependent on the weakness of the central government (e.g., during the civil war in 1992-1996), its tolerance of extremist organisations (connections between the Taliban and Al-Qaida), and the deterioration in the living standards of the population, which strengthened the motivations towards radicalisation and increased internal ethnic and religious tensions. Today, there is a risk of an intensification of the activities of various extremist groups in Afghanistan to take advantage of the Taliban’s weakness, especially in the transition period before their power solidifies.

Terrorist groups active in Afghanistan are either allied with the Taliban and have developed pragmatic relations with them, including Al-Qaida, or are in direct conflict with them, such as ISIS-K, and trying to take over areas where the Taliban have limited control of the country's territory. Such groups allied with the Taliban assume that the brotherhood of arms and their tribal and business affiliations will allow them to conduct training and logistics activities in Afghanistan, despite the 2020 Doha Agreement with the U.S. in which the Taliban pledged to fight terrorist groups. The aim of these groups is to build a base from which they can intensify activities against their enemies around the world (especially Al-Qaida) or in neighbouring countries (such regional groups as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, the Islamic Jihad Union, the Islamic Movement of Eastern Turkestan, and Lashkar-e-Taiba). The goal of ISIS-K, which is hostile to the Taliban, is to create in Afghanistan a caliphate, a territorial organization ensuring the observance of the principles of extreme Islam in its purest and radical interpretation, similar to the declared caliphate in Syria and Iraq in 2013-2019.

ISIS-K’s Relations with the Taliban and Al-Qaida

ISIS-K’s ideas for Afghanistan conflict with those of the Taliban and Al-Qaida. This conflict has both territorial and ideological dimensions. ISIS-K’s long-term goal is to establish itself as a power that rivals the Taliban in Afghanistan, while Al-Qaida cooperates with the Taliban by recognising their territorial authority. ISIS-K is focused for now on local goals, including the creation of the caliphate, in which it is ready to fight other Muslims. Al-Qaida’s activity in Afghanistan is focused on organising terrorist activities aimed primarily at external enemies, including the United States. On ideological grounds, ISIS-K criticises the Taliban as too lenient in the application of Sharia law and accuses it of seeking international recognition, which, in its opinion, departs from the principles of jihad. Unlike the Taliban, ISIS-K ignores the international community and does not seek its recognition.

ISIS-K is constrained by its weak ties to local ancestral and tribal structures in Afghanistan, predominated by the Taliban and Al-Qaida. This makes it difficult to function in the country and to obtain support from the local population. ISIS-K’s efforts to strengthen its funding sources in Afghanistan, including by trying to engage the drug trafficking market, are also a source of conflicts between the groups and local Taliban and their leaders.

ISIS and Afghanistan

Despite the fall of the caliphate in Iraq and Syria in 2019, ISIS survived as an organisation and retained a network of branches around the world (which it calls provinces). At the same time, it changed its profile from a group focused on the administration of territory in Syria and Iraq to a decentralised terrorist outfit that conducts asymmetric activities (terrorism and guerrilla actions) over a wide geographical area, focused on taking advantage of the weaknesses of local governments or intensifying ongoing conflicts. Its affiliates allow ISIS to maintain the reach of its propaganda and financial and organisational resources, recruit foreign fighters, and enable them to rotate between conflicts. One of its several “provinces” is Khorasan (ISIS-K), established in Afghanistan in 2015. In its concept, ISIS-K refers to the historical region of Khorasan, which also includes parts of the territories of Central Asian states, Iran, and Pakistan.

ISIS-K has about 2,000 fighters in Afghanistan (mainly from Pakistan, Syria, and Iraq). Since 2020, it has been led by the Iraqi Shahab al-Muhajir. ISIS-K uses its financial resources, recruitment, and propaganda channels developed during the jihad in Iraq and Syria in 2013-2019. At that time, at least several thousand fighters from the region took part in the fighting on the ISIS side, including ones from Central Asia, Pakistan, Indian Kashmir, and Chinese Xinjiang. ISIS-K remains most active in Afghanistan’s southeast, in the provinces of Kunar, Kandahar, and Nangarhar.

ISIS-K follows the tactics of Al-Qaida’s operations in Iraq in 2003-2006, which are based on the intensification of bombings to undermine the authority of the central government and degrade its ability to ensure security in a given territory, and the aggravation of ethnic and religious tensions. In 2015-2021, ISIS-K carried out more than a dozen attacks in Afghanistan each year. Its goal is to use the destabilisation of Afghanistan to expand its structures, combat units, and secret cells. The means to accomplish this include the reconstruction of regional alliances with, for example, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (which in 2015 declared its allegiance to ISIS) or the Islamic Movement of East Turkestan (several hundred members of the group joined the ranks of ISIS in Iraq and Syria). ISIS-K also wants to infiltrate Taliban structures, recruit fighters released from Afghan prisons during the Taliban offensive, and intensify the influx of volunteers from other countries in the region, which would allow it to scale-up its operations.

Conclusions and Perspectives

ISIS-K is weaker than the Taliban or their ally Al-Qaida, but it has managed to build structures and raise financial resources to conduct long-term guerrilla warfare and terrorist activities in Afghanistan. The Taliban will most likely not be able to fight it, especially since they do not have sufficient anti-terrorist and anti-insurgency capabilities. ISIS-K is for now forced to conduct underground activities on a limited scale. Nevertheless, it will likely develop the capacity to maintain a chronic asymmetric conflict that adversely affects stability in Afghanistan.

In the long term, ISIS-K has the potential to become the centrepiece of the global ISIS network, attracting militants from other affiliates, part because of the weakness of the Taliban but also the withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan, which weakens the logistic base of American anti-terrorist operations, necessary for an effective fight against ISIS and its regional “provinces”.

ISIS-K thus may generate a terrorist threat not only to Afghanistan and its neighbourhood but also to Europe. Despite its regional focus, the group’s development in Afghanistan may provide a foothold for the preparation of terrorist activities in other parts of the world (including propagandistic attacks to attract foreign fighters). This would enable the group to carry out operations in European countrie, which would increase the risk of terrorism on their territory similar to the attacks in 2015-2017.