The Potential Threat of the Ties between the Taliban and Al-Qaida

The collapse of Afghanistan’s government and security forces might increase the terrorist threat to the U.S. and Europe. During the period before 11 September 2001, the leaders of Al-Qaida and the Afghan fundamentalists cooperated closely. According to UN estimates, there are currently between a few hundred to a thousand members of Al-Qaida in Afghanistan. Despite weakening since the death of Osama bin Laden, Al-Qaida in future might use Afghanistan to regroup and as a safe haven.

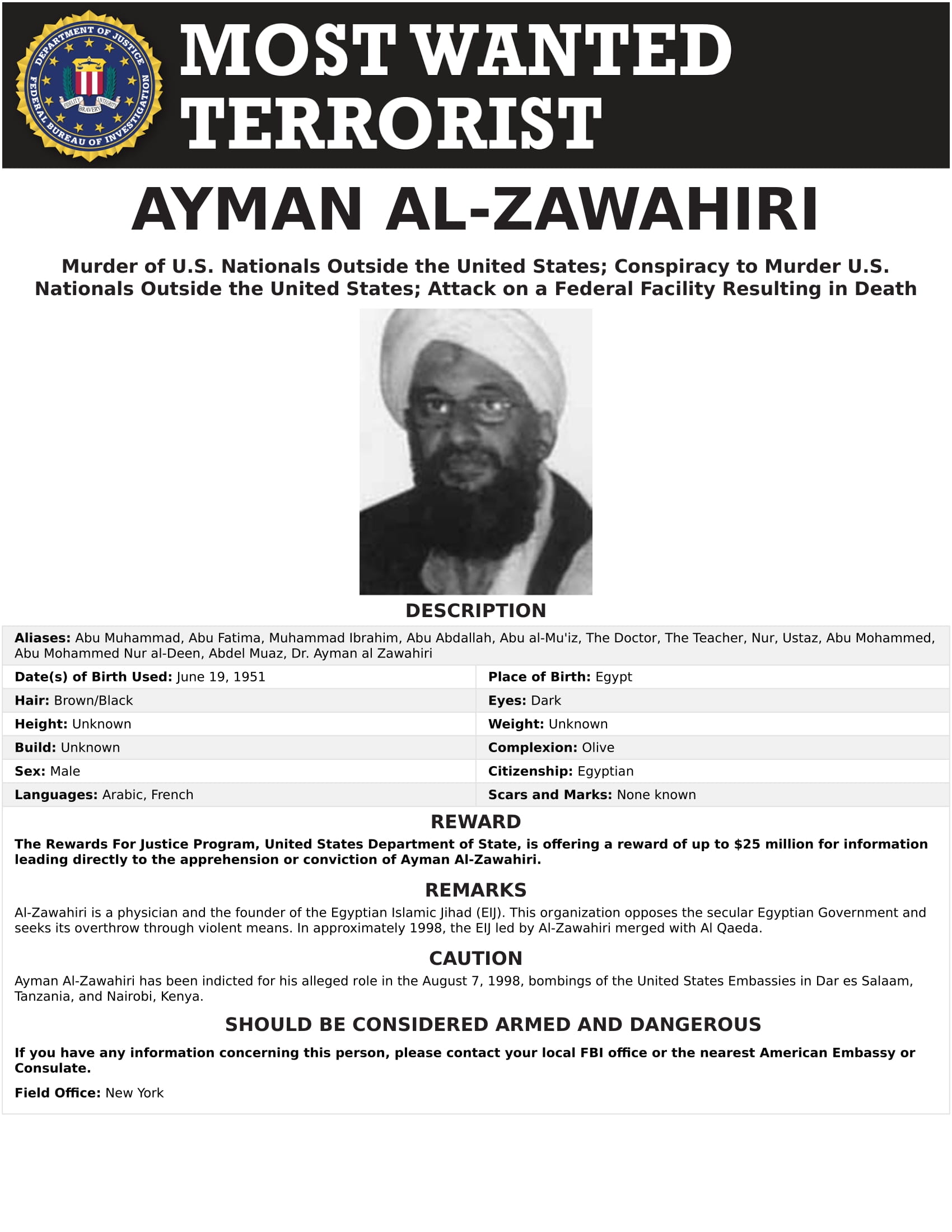

Photo: FBI

Photo: FBI

Evolution of Ties

Since the founding of the Taliban movement in 1994, the group has cultivated ideological, organisational, and individual ties with other Sunni extremist groups form the Middle East and South and Central Asia. These ties are rooted in the period of the 1980s and the influx of Arab volunteers into the ranks of the Afghan mujahedeen fighting Soviet intervention. Contrary to other Afghan factions, the Taliban gave protection to the leaders of Al-Qaida, which made it easier to expand this global terrorist network. The Taliban, despite support from Saudi Arabia where bin Laden was a wanted figure, refused to expel him. The sustained presence of Al-Qaida in Afghanistan and its border area with Pakistan allowed dozens of small terrorist training camps to open, through which passed thousands of volunteers from Muslim, European, and post-Soviet countries. Al-Qaida’s infrastructure in Afghanistan in 1996-2001 also helped the expansion of other extremist groups, threatening the states of origin of the now-trained terrorists. Examples groups that recognised the leadership of bin Laden and were affiliated with Al-Qaida in 1998 include the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, which sought destabilisation in Central Asia, and many Kashmiri fundamentalists who conducted terrorism and an insurgency against India. The symbiosis between Al-Qaida and the Taliban was strengthened by mixed Arab-Pashtun marriages of some leaders of the two organisations.

After the Al-Qaida attacks on New York and Washington in September 2001, the Taliban refused to expel the terrorist leadership. Then, Al-Qaida leaders found a safe haven in the tribal areas of Pakistan. Mullah Omar directed the movement from Pakistan (Quetta and Karachi) up to his natural death in 2013.

The surge in NATO forces in 2009-2012 militarily weakened the Taliban and Al-Qaida units in Afghanistan, and CIA drone attacks in northern Pakistan eliminated a few dozen mid- and high-level terrorist leaders. Al-Qaida was further weakened by the successful U.S. commando raid against bin Laden in Pakistan’s Abbottabad in May 2011, as well as by his successor, the not-charismatic Ayman al-Zawahiri, whose leadership was unsuccessful in attempting to ride on the back of the “Arab Spring”. Another issue for Al-Qaida was that its affiliate in Iraq refused to subordinate to either bin Laden or al-Zawahiri, independently gaining military success as the now well-known ISIS.

The significance of the conflicts in Yemen, Iraq, Syria, and Libya for another generation of Arab jihadists further seriously weakened Zawahiri’s “Central” direction. This trend was not reversed even as the Taliban in Afghanistan rebuilt after 2014. A new dynamic in Afghanistan and Pakistan came with the emergence of local ISIS cells in both countries, which came into direct conflict with both Al-Qaida and the Taliban. In 2016, Zawahiri re-cemented and confirmed the previous ties between the fundamentalist groups and declared loyalty to Mawlawi Hibatullah Akhundzada, the next leader of the Taliban.

Potential Threat from Al-Qaida

The collapse of the pro-western Afghan security forces creates new opportunities for Al-Qaida to regain its key role in the jihadist movement, at the expense of ISIS. From the point of view of Zawahiri, this can be connected to the enormous symbolic potential of the chaotic withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan and the upcoming 20th anniversary of the terrorist attacks on America. The victory over the government in Kabul fits into his narrative about the fairness and effectiveness of the militants’ struggle with superpowers (first the USSR, now the U.S.), a refreshing of jihadi ideology and mythology, and his personal role. It is very likely that Al-Qaida will move its “Central” direction from Pakistan to some part of Afghanistan. This would make it easier for it to regroup and rebuild terrorist training infrastructure and gain new funds from sympathisers of Al-Qaida. Because “Central” will be interested in regaining its historical status and pre-2001 capabilities, it is also likely that there will be renewed terrorist threats from its full members, or those affiliated with or who sympathise with Al-Qaida. In time, the group might also rebuild its potential out of the Afghanistan-Pakistan area. This would change the modus operandi of jihadists from the current “lone wolf”, very small attack cells to a broader, more organised version that seeks to stage spectacular and bloody attacks against the U.S. or EU countries. The increased terror threat would also affect weaker states in Central Asia, as well as Russia and India, both already struggling with their own jihadist separatists. The threat of this should be taken seriously despite the not credible Taliban pledge of 2020 that it will not permit the use of Afghanistan territory by terrorists. They have freed thousands of jailed radicals from Afghan jails, among them an unknown number of Al-Qaida. The Taliban will not be forced to break their relationships with Al-Qaida if the new regime is not really threatened by U.S. military intervention on a larger scale. Because the Afghan fundamentalists are not currently in control of all the territory of Afghanistan, and most likely won’t be in future, in case of Al-Qaida attacks against the West, the Taliban might argue they had no role in it. However, because Al-Qaida planners and assault forces were very important in the latest offensive to reach Kabul, they might expect the regime’s respect, gratitude, and protection. Moreover, since Omar’s death, the Pashtun Haqqani network has gained even more influence over the Taliban movement. The Haqqani have for almost three decades been the group most closely and personally connected to Al-Qaida “Central”, while their privileged position among Talibs is supported by the even longer enduring cooperation with Pakistan’s military intelligence. Taliban public declarations and contacts suggest better relations with China, Russia, and Iran, but it seems very unlikely that the Haqqani will be motivated to break with the ideology and person of Zawahiri.

Implications for NATO and EU States

The many reports about the current shape of Al-Qaida are impossible to verify from open sources. Intelligence assessments of the transnational terrorist threat will be complicated after the withdrawal of the U.S. troops from the country and likely loss of CIA human intelligence assets. These estimates will be complicated by even more limited (if any at all) cooperation on counter-terrorism with Pakistan, which in essence hosted the Taliban and tolerated Al-Qaida leaders after 2001. Contrary to declarations by the Biden administration, the ideological, organisational, and individual ties between Al-Qaida and the Taliban will persist, increasing the threat of new terrorist attacks on NATO and EU countries. The scale, sophistication, and timing of these attacks will be determined mainly by the need for Al-Qaida to regain its prestige and operational capabilities. One ongoing barrier to international terrorism is still the COVID-19 pandemic. An equally important factor the probability of new relationships or increased rivalry between Al-Qaida’s “Central” and ISIS’s local affiliates. Moreover, even if Zawahiri’s ambitions remain unfulfilled, a fundamentalist-led Afghanistan may inspire new generations of jihadis and sympathisers. For Al-Qaida, the best-case scenario is to regain Afghanistan as a safe haven for the most experienced and well-organised terrorist groups. The chaotic end to NATO intervention in Afghanistan and lack of assistance from Pakistan will complicate counter-terrorism actions against Al-Qaida leadership and terrorist camps. The loss of credibility of the U.S. and other western states among younger Afghans will complicate any planning or operations in future. In the short term, another factor will be the lack of a strong and local politico-military force comparable to the Northern Alliance before 2001. Taken together, all these factors raise the level of difficulty for the intelligence and internal security services of NATO and EU states.