Poland and South Korea Should Further Develop Security Cooperation

In the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, security and defence issues have assumed a more prominent role in Polish-South Korean relations. However, for these issues to become a pillar of their strategic partnership, it is essential to understand what divides the two countries, including in their perceptions of threats. Deepening existing cooperation is contingent upon embedding it in a broader strategic framework that encompasses security interdependence between Europe and East Asia.

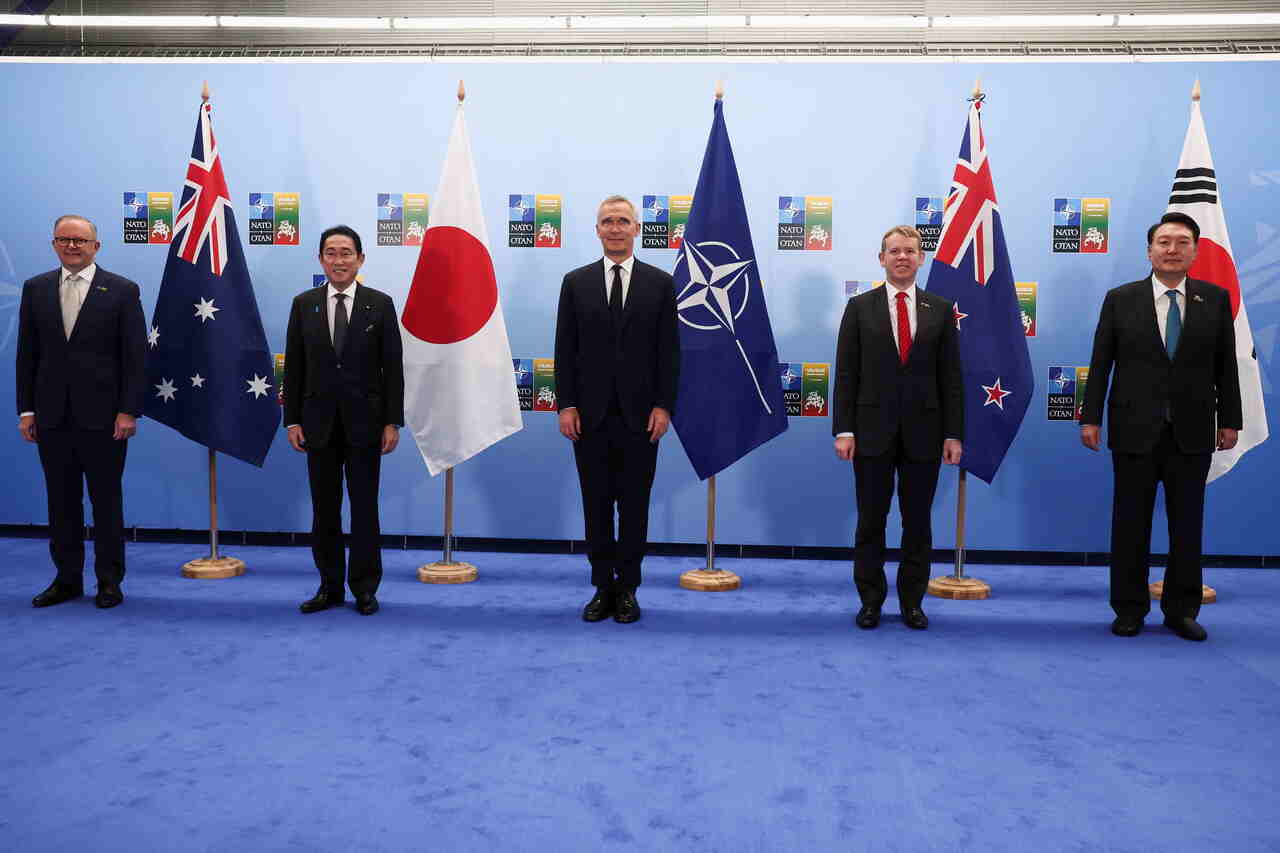

.png) JEON HEON-KYUN/POOL / Reuters / Forum

JEON HEON-KYUN/POOL / Reuters / Forum

South Korea is one of four Asian countries with which Poland has elevated relations to the status of a strategic partnership (China in 2011, South Korea in 2013, Japan in 2015, India in 2024). Since the establishment of diplomatic relations 35 years ago on 1 November 1989, economic cooperation has been paramount, particularly in regard to South Korean investments in Poland. The impetus for the development of economic contacts was primarily the accession of Poland to the European Union in 2004 and the subsequent implementation of the EU-South Korea Free Trade Agreement in 2011. Statistics Poland shows the value of trade in goods in 2023 exceeded $11 billion, with Poland recording a deficit of almost $9.5 billion. This is primarily attributable to investment imports generated by South Korean companies bringing in components and machinery for production facilities in Poland. According to the National Bank of Poland, the aggregate value of South Korean investment in Poland in 2022 was around $7 billion, making South Korea the largest non-European investor and among the 10 largest foreign investors in Poland.

In the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Polish-South Korean collaboration has taken on a new dimension. Following the transfer of a considerable quantity of military hardware to Ukraine comprising more than a thousand pieces of different equipment, including tanks, armoured personnel carriers, infantry fighting vehicles, self-propelled howitzers, rocket launchers, aircraft, and helicopters, and in light of the prevailing security concerns surrounding Russia, Poland has elected to procure equipment and armaments from South Korea as part of a comprehensive programme to modernise the Polish Army. Additionally, there has been an intensification of political dialogue, as evidenced by the first visit to Poland in almost 14 years by a president of South Korea, in July 2023, and by the visit of the president of Poland to the Republic of Korea at the end of October this year.

Development of Cooperation in the Defence and Security Dimension

In the last two years, South Korea has emerged as a significant supplier of military equipment to Poland, alongside the United States. The contracts concluded with Poland are of record value for the South Korean arms industry. Poland has thus become an important source of revenue for South Korean defence companies and a potential gateway into the European defence market.

To date, the value of arms contracts signed on the basis of the general 2022 framework agreements is estimated at $16.6 billion. The contracts include the purchase and delivery from South Korea to Poland of 180 K2 tanks by 2025, 364 K9/K9PL self-propelled howitzers by 2027, 290 K239 Chunmoo multiple rocket launchers by 2029, and 48 FA-50/FA-50PL light combat aircraft by 2028. To date, 62 K2 tanks, 108 K9 howitzers, 46 K239 launchers, and 12 FA-50 aircraft have already been delivered to Poland.

The framework agreements envisage the acquisition of a much larger number of South Korean armaments (up to 1,000 K2/K2PL tanks and 672 K9/K9PL howitzers) and, above all, part of their production in Poland from 2026 under an industrial cooperation deal. Production would include some of the 820 tanks in the K2PL version, 460 howitzers of the K9PL type, and the 288 K239 launchers (Polish military designation “Homar-K”) and missiles of various types used in them. The technology transfer envisaged in the framework agreements would also serve to establish an industrial capability in Poland to service and modernise the equipment (including the FA-50 aircraft).

The benefits negotiated and confirmed so far for Polish industry include the installation of K239 launchers on Polish Jelcz chassis and their integration, like the K9, with the indigenous Topaz fire control and Fonet communications systems (the latter is also in K2 tanks). Implementing agreements specifying the terms of industrial cooperation are still being negotiated. For example, the executive contract for the supply of Homar-K launchers concluded in April this year stipulates that 60 of the 72 modules ordered for the 2026-2029 period are to be manufactured in Poland.

Poland’s industrial and defence cooperation with South Korea fits into the strategic context of escalation scenarios from Russia against NATO and the growing links between the security of Europe, especially the Alliance’s Eastern Flank, and the situation in the Asia-Pacific region.

The provision of equipment and armaments from South Korea on a short-term basis enables Poland to rapidly rebuild and further strengthen its military capabilities in order to defend against a potential Russian threat to it and NATO. The timeframe for the implementation agreements encompasses a period during which Russia, under circumstances favourable to it, including a freeze of the conflict with Ukraine, could potentially rebuild the conventional capability to probe and destabilise NATO’s Eastern Flank. In contrast, the framework agreements, which could extend to over the next 10-15 years, cover a timeframe in which the projected threat from Russia could even take the form of aggression against a member of the Alliance.

The collaboration with South Korea has resulted in Poland’s acquisition of new military capabilities, which has led to a long-term reinforcement of the defence and deterrence capabilities of the Alliance’s Eastern Flank. Furthermore, this is an integral aspect of the political dialogue between NATO and countries in the Asia-Pacific region, a discussion that was invigorated following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The NATO-IP4 mechanism (involving Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and the Republic of Korea, known until recently by the acronym “AP4”) provides a useful platform for Poland’s cooperation with South Korea in the security dimension. The interdependence in security between Europe and Asia, emphasised at NATO-IP4 meetings, provides an impetus for the Polish authorities to take a greater interest in the security environment of East Asia, and for South Korea’s in the situation in Central and Eastern Europe. One of the most promising areas of this enhanced cooperation is in responding to cyberthreats emanating from Russia, North Korea, and China. Since 2023, South Korea has participated in NATO cybersecurity exercises through its membership of the NATO Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence. Furthermore, the establishment of the NATO-Ukraine Joint Analysis Training and Education Centre (JATEC) in Bydgoszcz has created opportunities for cooperation between the Republic of Korea and NATO. This could potentially facilitate the transfer of information on North Korean munitions and armaments used by Russia in Ukraine to South Korea.

An additional crucial aspect of the bilateral security collaboration between Poland and South Korea is the advancement of the industrial-defence partnership. Poland is interested in facilitating the maintenance, overhaul, and repair, and ultimately the production, of South Korean armaments at Polish defence industry plants, with components developed by domestic companies. The transfer of South Korean technology is intended to facilitate the production of ammunition, components, and spare parts for the weapons systems acquired from South Korea. This is fundamental for Poland’s security on NATO’s Eastern Flank. Ensuring high readiness of the armed forces to operate in conditions of an escalating crisis or conflict requires, as the experience of Ukraine indicates, free access to a technological and industrial base that is sufficiently developed to enable damaged armaments to be quickly restored to service, as well as the provision of ammunition and other expendable components at the level required by operational realities. Such calculations influence Poland’s expectations towards South Korea in terms of technology transfer and cooperation in the manufacture of armaments. In the longer term, the partnership with South Korea is also seen in Poland as a potential opportunity to increase the competitiveness of the domestic defence industry, which could offer new products, developed in cooperation with South Korean partners, also on foreign markets

Challenges in Strategic Perceptions

The intensification of Poland’s cooperation with South Korea in the defence dimension was forced by the consequences of the Russian aggression against Ukraine. It is also the result of South Korea seeing Poland primarily as an attractive market for the South Korean arms industry. The promotion of arms exports enjoys cross-party support in South Korea and is part of the pro-export economic model of its defence industry. Moreover, despite the successes achieved so far, a number of limitations in Polish-South Korean cooperation have become apparent over the past two years.

The key issue is Poland’s and South Korea’s differing perceptions of the threats they face. Poland identifies Russia’s imperial policy and military capabilities as the primary source of concern, while South Korea’s focus is on the threat posed by North Korea and avoiding tensions with Russia and China. This divergence in focus has resulted in a lack of cross-party consensus in South Korea on supporting Ukraine and deepening cooperation with NATO.

The majority of the South Korean public is in favour of providing support to Ukraine, but only if it is in the form of humanitarian and development aid, rather than arms supplies. In a National Barometer Survey conducted in June of this year, 55% of respondents opposed the provision of arms to Ukraine, while 35% expressed support for such a move. These results were comparable to those of the April poll, indicating that even the intensification of North Korean military collaboration with Russia has not altered the South Korean public’s stance on providing arms to Ukraine. This was corroborated by a Gallup Korea survey conducted at the end of October that found 66% of respondents advocated non-military assistance to Ukraine, while only 13% endorsed the provision of arms.

The hesitancy to provide military assistance to Ukraine can be attributed to concerns about the potential for South Korea to become embroiled in a conflict that could have detrimental consequences for the country’s security and economic prosperity. Despite condemning Russia for its aggression and joining the sanctions against it, South Korean authorities have indicated a willingness to resume stable relations with the Russian Federation following the end of the conflict in Ukraine. Additionally, some South Korean companies continue to sell, among other things, advanced industrial machine tools to Russia through subsidiaries in China, thus circumventing government export restrictions. Some officials, as well as researchers and academics, espouse the Russian perspective, including the view that NATO was responsible for provoking the war in Ukraine. The 20-year technological collaboration with Russia, which included the development of South Korea’s missile arsenal, may also be a contributing factor. The ambiguous stance towards the Russian Federation may limit the Republic of Korea’s willingness to support the Alliance in the event of a potential conflict with Russia.

The minimal interest in Ukraine among both political experts and the general public in South Korea represents a significant challenge for the government. Thus far, it has been unable to develop a sufficiently compelling narrative that could inspire greater engagement with issues in Central and Eastern Europe and foster support for more robust assistance—including military—for Ukraine. This limited interest in international matters beyond the Korean Peninsula contrasts starkly with the government’s stated aspirations for South Korea to become a global, pivotal state with a more prominent role on the global stage.

Despite South Korea’s deepening cooperation with NATO, policymakers and back-office experts have limited knowledge of the Alliance. In light of the ongoing debate surrounding the potential development of nuclear weapons by South Korea, the focus of interest in the country is primarily on the operational specifics of the NATO Nuclear Planning Group rather than on the practical aspects of collaboration with the Alliance. Some politicians and experts in opposition to the government of President Yoon Suk-yeol have expressed criticism of the deepening of relations between the Republic of Korea and the Alliance. They view this as another manifestation of the pro-American orientation of the government, following rapprochement with Japan and the intensification of the U.S.-Japan-South Korea trilateral cooperation. In this context, they highlight the potential for South Korea’s collaboration with NATO to elicit a negative response from China, which they see as helping to maintain stable relations on the peninsula. The reluctance to provide arms to Ukraine and the uncertainty surrounding cooperation with NATO may complicate Poland’s collaboration with South Korea in terms of the transfer of South Korean armaments from Poland to Ukraine, among other areas.

Recommendations

It is in Poland’s interest to utilise the current level of rapprochement in defence relations with South Korea in order to reinforce the strategic partnership between the two countries, thereby enhancing its resilience to internal and external changes that may disrupt cooperation. In order to ensure that the partnership is not based solely on the contracts that have been concluded thus far, it is necessary to embed it in a deeper and expanded network of dialogues and initiatives. It would be beneficial for Poland to engage in discussions at the political, military, and expert levels. Poland should consider developing not only contacts with the current government of the Republic of Korea, but also with the opposition. It is important to consider the potential impact of the opposition candidate’s victory in the 2027 presidential elections, which could result in shifts in policy towards NATO, Ukraine, and Russia, among other matters.

Furthermore, it is necessary to integrate Poland’s collaboration with South Korea into a more comprehensive strategic framework. The development of Polish-South Korean cooperation would benefit from a more detailed consideration of the regional and global security context than has thus far been the case. In addition to bilateral issues, topics such as support for Ukraine and post-war reconstruction, policy towards Russia, China and North Korea, and the future of relations with the U.S. should be a permanent element of the discussions and consultations between Poland and South Korea. In the coming years, the delivery of military equipment (as has been the case for years with electronics, cars, etc.) will be made by sea from the Korean peninsula, almost 8,000 km away. It is therefore in Poland’s interest to take a greater interest in the security situation in the Asia-Pacific region, including by working with South Korea and other partners and allies to ensure freedom of navigation. Furthermore, it would be prudent to consider potential negative scenarios, such as direct aggression against Poland or South Korea, and the impact of other international conflicts on Polish-South Korean relations.

Additionally, Poland could engage in diplomatic dialogue with South Korea at the political and military levels with the objective of enhancing bilateral cooperation in the security domain, encompassing a broader scope of areas. Discussions could be held between Poland and South Korea on the approach to the development of conventional deterrence, including the role of air and missile defence and long-range precision strike capabilities. Russia’s cooperation with North Korea, including its impact on the Russian-Ukrainian war, its response to the threat of nuclear escalation on their part, and both partners’ cooperation with the U.S. in nuclear deterrence necessitates a comprehensive examination and exchange of information. It may also be beneficial to consider exchanges of experience and information on military doctrines, operational issues, modernisation of the armed forces, and recent armed conflicts (e.g., Russia-Ukraine, Israel-Hamas, and Israel-Hezbollah). The possibility of establishing even symbolic programmes of joint exercises and military visits could also be explored. In particular, the exchange of experience in combating hybrid and grey-zone operations and use of special forces may prove fruitful.

Given existing agreements for the purchase of armaments from South Korea, it is in Poland’s interest to pursue enhanced collaboration between its defence industries. It is of the utmost importance to establish mutually beneficial agreements that encompass the maintenance, repair, overhaul, and production of imported weapons systems in Poland, with the potential for them to be exported to other countries. It is in Poland’s interest that defence cooperation with South Korea extend beyond the purchase of armaments and the transfer of older technologies. In order to achieve this, it would be beneficial to identify areas of cooperation beyond the scope of the existing programmes. One particularly valuable avenue for such cooperation would be the initiation of joint research and development of military capabilities based on innovative defence technologies.

The growing security interdependence between Europe and Asia should also encourage Poland and South Korea to make their partnership more strategic. This would entail intensifying dialogue at various levels, taking greater account of the regional and global security context, and deepening cooperation in further areas. Such a response would serve to address the numerous challenges and threats facing both countries. The further development of the strategic partnership would demonstrate not only the desire to make bilateral cooperation more dynamic, but also the readiness of both Poland and South Korea to pursue a more global foreign policy.

.jpg)