NATO Intensifies Cooperation with Indo-Pacific Partners

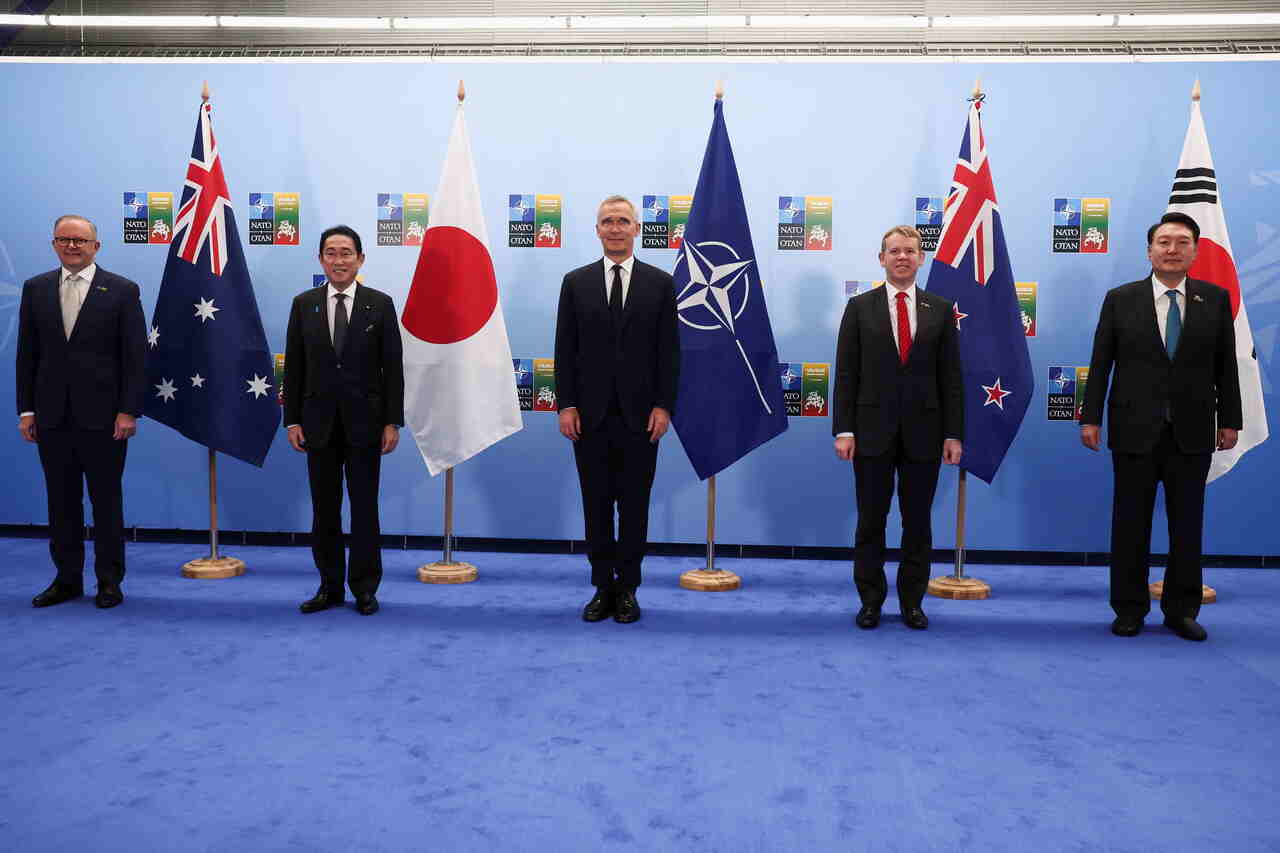

The participation of the leaders of Australia, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand (AP4) at the NATO summit in Vilnius in July this year confirmed that the Alliance recognises the interdependence of the security of the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific areas. The organisation intends to develop cooperation with the AP4 in cybersecurity, new technologies, and combating hybrid threats, among others. Challenges to collaboration include the divergent positions among NATO countries and its Indo-Pacific partners in their approach to China. It is in Poland’s interest to support the Alliance’s cooperation with the AP4 without weakening NATO’s commitments in Europe.

KACPER PEMPEL/Reuters/Forum

KACPER PEMPEL/Reuters/Forum

This year’s NATO summit in Vilnius was the second in a row attended by AP4 leaders. During the event, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg announced new Individually Tailored Partnership Programmes (ITPPs) for 2023-2026 with Japan and South Korea. Following the summit, the Alliance concluded a similar agreement with Australia, and a deal with New Zealand is being negotiated. At the same time, in Vilnius, NATO had yet to decide to establish its liaison office in Tokyo, which had been discussed since January when Stoltenberg made such a proposal during his visit to the Japanese capital. The lack of a decision on this matter highlighted the differences in the approach of the NATO allies to cooperation with Indo-Pacific partners and the resulting limitations.

Basis for Cooperation

The factor that brings the AP4 and NATO states together is a commitment to a rules-based international order and shared values of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. Cooperation is determined by the growing security interdependence of the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific areas, as embodied in NATO’s 2022 Madrid Strategy and reiterated in the Vilnius Summit Communiqué. Their cooperation also stems from a growing awareness of China’s challenges to the security, interests, and values of both the NATO and AP4 states and deepening Sino-Russian cooperation, which is undermining the rules-based international order in the partners’ view. Thus, from the Alliance’s perspective, an escalation of tensions or even conflict in the Indo-Pacific, for example, in the Taiwan Strait or on the Korean Peninsula, would not only have political and economic significance for Europe and the U.S. but also could prompt Russia to intensify its aggressive actions in Europe.

U.S. interests and actions also influence NATO’s deepening cooperation with the AP4. The U.S. seeks to coordinate its policy towards China with its European and Asian allies. The U.S. also counts on European NATO members’ collaboration with the AP4 to relieve the U.S. of the pressure to maintain capabilities to participate in full-scale wars simultaneously in the Indo-Pacific and Europe. The U.S. allies meet its expectations to maintain an American military presence in their regions. Indeed, both the Asian and European allies of the U.S. are accompanied by uncertainty about the future shape of U.S. foreign policy. The experience of the Trump administration suggests that a more isolationist U.S. government may attach less importance to alliances and take less account of allies’ perspectives in its policy.

Opportunities

NATO’s further rapprochement with the AP4 provides a chance to intensify the political dialogue, consultation, and coordination concerning common challenges and threats in the security dimension. The ITPP agreements indicate the broad scope of potential cooperation. According to them, the Alliance intends to develop cooperation with Indo-Pacific partners in cybersecurity, hybrid threats, intelligence-sharing, new technologies, climate change, disarmament, arms control and non-proliferation, and strengthening military interoperability, among others.

NATO’s cooperation with the AP4 is also conducive to maintaining Indo-Pacific partners’ support for Ukraine and Alliance countries in the aftermath of Russian aggression. Regarding supplies of military equipment and ammunition to the invaded country, Australia stands out, giving howitzers and armoured personnel carriers, among other equipment. The New Zealand government has provided funds to the United Kingdom’s government to purchase arms and ammunition supplied to Ukraine, and New Zealand military personnel have been training Ukrainian soldiers in the UK. South Korea has supported Ukraine with supplies of, among other things, helmets, body armour, and demining equipment. It has also sold significant quantities of armaments to Poland, including as a replacement for Polish military equipment transferred to Ukraine, and offered defence industry cooperation. However, the South Korean authorities have not authorised direct arms transfers to Ukraine and denied reports that they were to transfer artillery munitions to the Ukrainians through the U.S. or other countries. Japan has provided similar support to South Korea while offering significantly more financial, humanitarian, and development assistance (over $7 billion in total since last February, including $5.5 billion in World Bank aid bank guarantees; in comparison, South Korea has committed $250 million).

Limitations

The most severe constraint on NATO’s cooperation with the AP4 are the differences in countries’ attitudes towards China. This was highlighted by France’s opposition to the idea of the establishment of a NATO liaison office in Tokyo. According to the French authorities, this move would exacerbate relations with China and not add practical value vis-à-vis the NATO Contact Point currently operating at the Danish embassy in Tokyo. France’s opposition corresponds with Germany’s new strategy towards China, which emphasises the need to maintain the political dialogue despite growing challenges, especially economic ones, arising from Chinese policy. The lack of a decision to establish a NATO office indicates the resistance of some member countries to the U.S. vision of the development of the Alliance, which, under the influence of years of American advocacy, has included threats from China in its strategy. Nor do the AP4 countries present a unified position towards China, although all of them have sharpened their stance in recent years. South Korea and New Zealand seem most inclined to maintain a conciliatory approach towards China.

A more profound dialogue with the AP4 and greater attention to China may raise concerns among some European NATO members that the Alliance is being distracted from collective defence and deterrence tasks in the treaty area, namely Europe, North America, and the North Atlantic. Most European countries are also interested in cooperating with the Alliance’s Indo-Pacific partners mainly in the economic, rather than security sphere. Buying armaments from outside Europe and entering into defence cooperation, as in the case of Poland and South Korea, is judged by some countries, for example France, as competition for European companies. The AP4 states, on the other hand, are aware of the low probability of NATO’s military involvement in a possible armed conflict in the Indo-Pacific. This is due to both the lack of formal NATO alliance commitments to countries in the region and insufficient military capabilities in most European countries. The AP4 can, however, expect NATO partners to act in other spheres, such as joining in with them on possible economic sanctions.

Conclusions

NATO will remain primarily a security organisation for the Euro-Atlantic area. Still, due to the deepening interdependence of global challenges and threats, it is expressing more interest in the Indo-Pacific. The renewed participation of Indo-Pacific leaders at the Alliance summit indicates that the informal NATO-AP4 format is becoming a mechanism for ongoing cooperation that adapts to the evolution of common challenges and threats.

Among the areas of possible cooperation, collaboration in cybersecurity and intelligence sharing seems most promising. While the NATO-AP4 format may focus on supporting Ukraine in the short term, the task will be to develop a coherent response to China’s actions in the longer term. Given the wide divergence of policy positions towards China, the development of a coordinated approach on this issue will be served by mechanisms operating in a narrower circle, such as the trilateral dialogue involving the U.S., Japan and South Korea, or AUKUS. Given the AP4 countries’ support for Ukraine, the European members of NATO should also be prepared to provide them with the analogous backing should a conflict in the Indo-Pacific arise.

It is in Poland’s interest to advocate within NATO for a formula for cooperation with AP4 that does not come at the expense of the Alliance’s defence and deterrence commitments in Europe. This may include establishing NATO liaison offices in the Indo-Pacific, which would enhance the possibility of regular consultations with regional partners. At the same time, deepening NATO’s cooperation with the AP4 requires Poland to take a greater interest in the Indo-Pacific security environment. This is about better understanding the Asian partners’ threat perceptions and U.S. priorities in the region. Following the example of the Czechia and Lithuania, it is advisable to create a strategic document defining the interests, objectives, and instruments of Polish foreign policy in the Indo-Pacific, including in the area of security.

.jpg)