EU Smoothly Developing Military Mobility in Europe

Democratic states can send military equipment to Ukraine faster thanks to EU military mobility, an initiative aimed at improving the transport of military personnel and assets across the continent. Unified military requirements as well as simplified transport procedures contribute to this. In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the EU updated its directions for the development of military mobility. Implementation of the plans will, however, require increased financial outlays, especially for protecting transport infrastructure and supporting partners such as Ukraine and Moldova.

.jpg) UKRAINIAN GOVERNMENTAL PRESS SER / Reuters / Forum

UKRAINIAN GOVERNMENTAL PRESS SER / Reuters / Forum

In November 2022, the European Commission (EC) and the High Representative (HR) introduced the Action Plan on Military Mobility 2.0. Its goals are further improvement of the transport of troops and military equipment, increased protection of the infrastructure necessary for this, unification of regulations in this area, as well as tightening cooperation with, for example, NATO and third countries important for ensuring peace and security in Europe. Plan 2.0 is an update to the 2018 document, and responds to the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the growing threat of escalation on the Russian side. Therefore, it implements the objectives of the March 2022 Strategic Compass, the EU’s security strategy, which indicates the need to increase the military mobility of the armed forces across the Member States and beyond Union borders.

Achievements So Far

The objectives of the 2018 Action Plan on Military Mobility have been achieved and the development of dual-use (civil-military) transport infrastructure takes into account the military requirements, including technical specifications and main military routes. It was approved in 2019 by the Council, and between 2021 and 2027, €1.69 billion was allocated for this purpose under the Connecting Europe Facility. The guidelines also allowed simplified customs procedures for military transport with the introduction of a single form, harmonised rules for the transport of dangerous goods, and exemptions for military activities under the Common Security and Defence Policy from VAT and excise duty, resulting in savings for Member States.

In addition to the Action Plan, EU institutions, together with Member States, are developing military mobility through other security initiatives. As part of Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), states are conducting two main projects—Military Mobility and Network of Logistics Hubs (in Poland, the hub in Kutno is to be fully operational by the end of 2024). The European Defence Agency (EDA) has since 2019 run the programme Optimising Cross-Border Movement Permission Procedures in Europe, under which technical arrangements for surface and air domains were signed in 2021. Moreover, under the European Defence Fund, the project Secure Digital Military Mobility System (SDMMS) received €9 million in funding and is being built to ensure information exchange between governments approving and requesting military movements by mid-2025.

Objectives of the New Plan

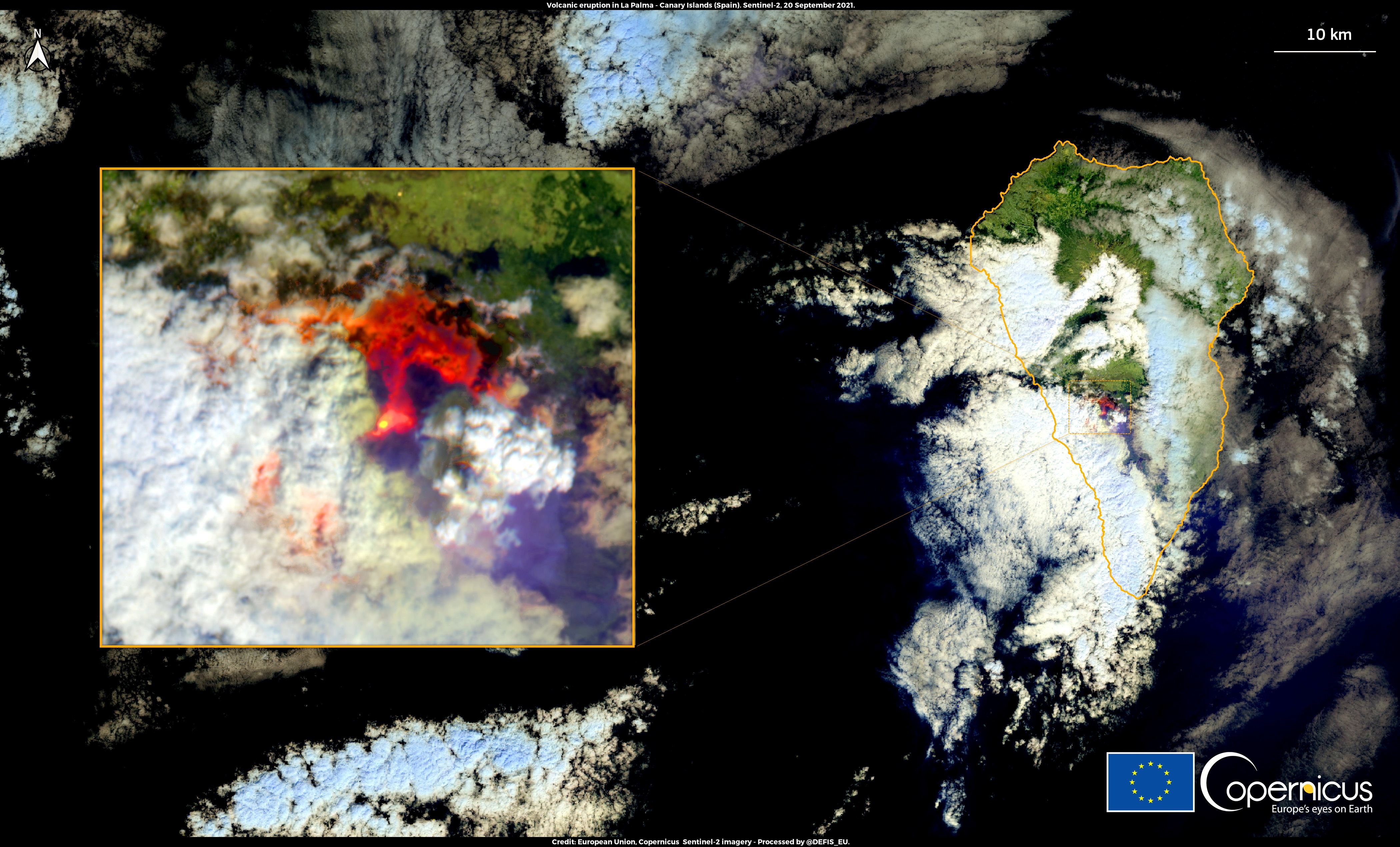

Plan 2.0 organises the development of military mobility until 2026. Its main goal is to eliminate gaps in transport infrastructure and secure fuel supply chains, as these are areas of key importance for the efficient transport of troops and military equipment in the event of a conventional armed conflict. An important new element of the plan is the improvement of infrastructure protection against hybrid threats, including cyberattacks, which is also substantial in view of the further digitisation of administrative procedures, such as cross-border movement permissions or customs forms. In addition, the objectives include improving transport capacity by air and sea, as well as increasing military energy efficiency and resilience to the effects of climate change. In the longer term, Plan 2.0 indicates also the need to analyse the links between military mobility and EU space programmes, such as Copernicus, Governmental Satellite Communications, or the European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service (EGNOS). What is crucial in the face of Russia’s aggressive actions is enhanced cooperation, which, apart from traditional partners such as NATO, the U.S., Canada, Norway, and the UK, is also to include the EU’s closest neighbourhood—Ukraine, Moldova, and the Western Balkans countries.

The Importance of Allied Cooperation

Actions in the military mobility field undertaken in the EU respond to the military needs of states, most of which are also NATO members (except Austria, Cyprus, Ireland, Malta, and Sweden). The cohesion of both organisations’ activities is essential and therefore the subject of permanent consultations between them, with military mobility one of the flagship examples. The list of common priorities set in the Seventh Progress Report on EU-NATO cooperation of June 2022 includes standardising military requirements, building transport infrastructure and increasing its resilience, simplifying customs procedures, facilitating cross-border movements, and dangerous goods transport. This corresponds to what is being done in the EU—an example of successful implementation is the transport infrastructure requirements, which are 95% in line with those of NATO.

The EU’s strength lies in its ability to engage partners in cooperation on military mobility. This is especially true for the PESCO Military Mobility project created in 2018. It serves as a political and strategic platform involving 25 of the 27 Member States (Denmark and Malta are not participating). At the end of 2020, it was opened to third countries, and in the first half of 2021 it was joined by the U.S., Canada, and Norway, followed at the end of 2022 by the UK. The interest in cooperation under the project indicates primarily its operational importance for cross-border military movement in Europe. In the case of the UK, it also shows an improvement in relations with European partners in the field of security, which remained tense after Brexit, although it does not break the impasse regarding institutional cooperation with the EU due to the intergovernmental nature of PESCO. Another important example is the EDA project overseeing the optimisation of cross-border movement permissions, which Norway joined in 2020.

Conclusions and Challenges for the Future

The Russian aggression highlighted the importance of military mobility in Europe and the need for efficient transport of military equipment to Ukraine, especially in the early stages of the war, when it was crucial to maintaining its defence capabilities. Therefore, the EU correctly defined the development directions of the security and defence policy, implemented, among others, under the Action Plan on Military Mobility from 2018 and updated in 2022, as well as PESCO and EDA projects such as Military Mobility, the Network of Logistics Hubs, and Optimising Cross-Border Movement Permission Procedures. In the face of the constant threat of aggressive Russian actions, shortening the reaction time of the armed forces is an important element of conventional deterrence in Europe. Poland, for example, already meets the target of five days for permits for regular units and three days for rapid-reaction units.

The EU has the competence to implement the objectives of military mobility, having at its disposal both financial, programmatic, and legal instruments. The detailed objectives of the Action Plan on Military Mobility 2.0, which take into account the specificity of the Russian invasion of February 2022 and its consequences for the security of European countries, should be positively assessed. In the short term, it will be particularly important to maintain the pace of adaptation of road, rail, and air infrastructure—mainly in Central Europe—to the threat from Russia. For example, Poland received support for the highest number of projects in the second contest under the Connecting Europe Facility (€33 million for five projects), which will strengthen several transport networks. In addition, it is worthwhile for Member States to invest more in building cyber resilience and improving the exchange of information on cyberthreats, especially in view of the digitisation of military procedures and the increasing number of attacks on critical infrastructure. In the longer term, it will also be necessary to integrate EU space imaging, communication, and navigation capabilities into military mobility.

The extension of military mobility cooperation to Ukraine, Moldova, and the Western Balkans is an important signal of political cohesion of the EU and its partners in the face of Russia’s aggressive actions. It should be the basis for the gradual inclusion of the countries covered by the EU enlargement process in the security and defence policy. At this stage, Poland is already seeking EU funds for the expansion and adaptation of transport networks towards Ukraine and Moldova where difficulties—apart from the insufficient number of routes—also concern the width of railway tracks, among other challenges. Further activities aimed at building the interoperability of the countries of the region with the EU and NATO, such as the dialogue on military requirements and joint exercises, should also play an important role.