EU Responses to the Potential of an Armed Conflict in the Taiwan Strait

The U.S.-China rivalry, development of China’s military potential, and growing nationalist Chinese rhetoric, including declarations about the future “reintegration” with Taiwan, increase the risk of an armed conflict in the Indo-Pacific in the coming years. Given the strong economic ties between EU countries and China, it is in the Union’s interests to decrease the likelihood of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan while reducing its dependence on China. For this, diversification is needed in the economic dimension, including developing the EU’s production potential and strengthening cooperation to maintain Taiwan’s security, especially with the U.S. and Japan. Moreover, starting work on a catalogue of possible sanctions if there is an attack on the island may act as a deterrent to China.

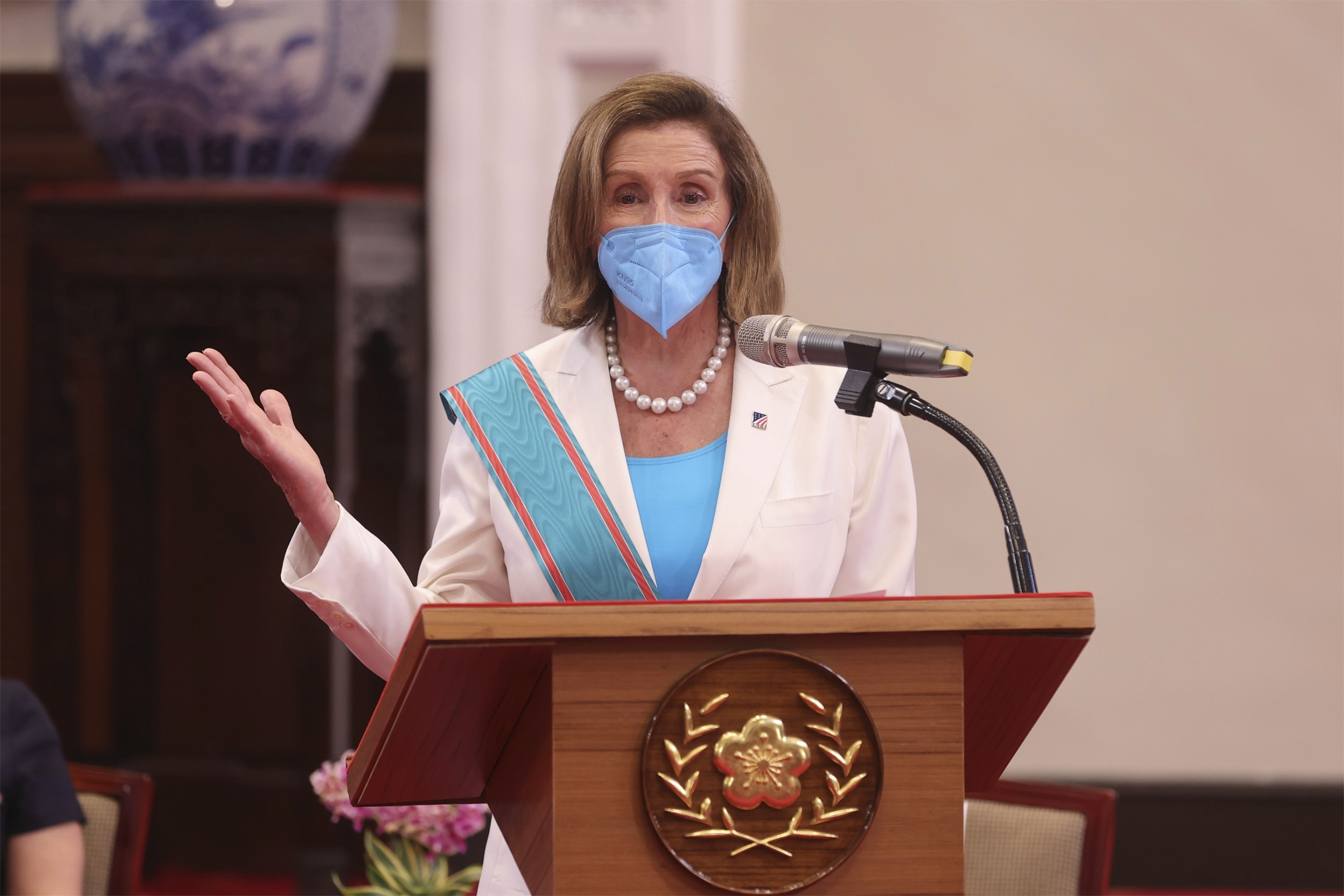

THOMAS PETER / Reuters / Forum

THOMAS PETER / Reuters / Forum

Increased Risk of an Armed Conflict

In the opinion of the Communist Party of China (CPC), a military confrontation with the U.S. is inevitable in the long term. Political differences between the two countries determine the United States’ drive to limit China’s development, and this threatens the survival of the Chinese regime, the stability of the social situation, and the legitimacy of the CPC. The party believes that the U.S. global potential is decreasing and that this increases the likelihood of China’s victory in a potential conflict, for example, over Taiwan. Nationalist sentiments and anti-Western rhetoric persist in the CPC, and the party’s power legitimacy is based on, among others, “reintegration” of the mainland with the island[1]. During the 20th CPC Congress in October, efforts to preserve China’s security dominated leader Xi Jinping’s rhetoric. In a report presented at the opening of the meeting, he stressed what he called the peaceful striving for “reunification” with Taiwan. The Chinese authorities are keenly aware, however, that this scenario contradicts the Taiwanese view against this idea.[2] Opposition to “Taiwan’s independence” was also included in the revised CPC charter. Gen. He Weidong, who most likely was responsible for overseeing the Chinese military exercises in the Taiwan Strait after U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s[3] visit to the island, became the deputy head of the Central Military Commission. This does not mean an acceleration of preparations for the invasion of Taiwan, but it confirms the seriousness of the CPC’s plans and the expansion of the potential to implement them, including the offensive capabilities of the Chinese armed forces.[4] It also is intended to act as a deterrent to the U.S. and its partners.

China emphasises that it remains ready to use force if Taiwan attempts to gain independence. Legally, this stems from the anti-secession law of 2005. According to the “Global Security Initiative” presented by Xi in April this year, China could use the pretext of a gradual undermining of the status quo by the U.S. and Taiwan (in the Chinese view, for example, cooperation between their armed forces or U.S. support for Taiwan’s membership in international organisations) as an excuse to use force in response to perceived threats to China’s security. In June, Xi ordered the Chinese armed forces to prepare regulations that would allow them to conduct “special military operations”, following the example of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Such decisions and actions increase the likelihood of China taking aggressive actions towards Taiwan in the coming years.

Crisis Scenarios and Signs of a Possible Invasion

A potential attempt to take the whole of Taiwan by armed force would probably be preceded by escalation actions aimed at the island and calculated to test the U.S. response. The type, sequence, and possible parallel nature of such actions would depend on the internal situation in China[5] and the dynamics of the international situation. It should be assumed that China would escalate tensions around Taiwan gradually. The first phase probably would be to intensify current, organised hybrid actions, such as disinformation directed at the Taiwanese, undermining the morale of society and the competence of the Taiwanese political elite to defend the island. In this way, China most likely would be aiming for a situation in which the Taiwanese recognise that “integration” with China is the only possible solution. The dimension of cyberattacks against Taiwan’s critical infrastructure, military and government offices, would also intensify. Another measure China could use would be to expand the area of military manoeuvres, including, for example, the People’s Liberation Army (ALW) vessels or aircraft regularly crossing the “median line”, an imaginary border in the middle of the Taiwan Strait, as recently happened in response to Pelosi’s visit. The next steps of escalation may include violations of Taiwan’s airspace, the use of economic pressures such as an embargo on the delivery of key goods to the island from China, and a maritime blockade of the island. Before deciding to invade, China also would likely multiply the production, purchase, and storage of ammunition, and complete the development of military infrastructure, such as intercontinental missile silos. It also may be possible to observe the suspension of the demobilisation of soldiers, the gathering of food supplies or key raw materials. Actions would also be taken to protect China’s economy against possible foreign reactions by, for example, limiting capital flows abroad or even freezing foreign assets in China.

Importance of the Indo-Pacific and the Taiwan Strait

The increase in the international role of the Indo-Pacific is primarily the result of its increasing importance in the world economy, the increasing Sino-American rivalry, and the related tensions in the region. In the U.S. National Security Strategy[6], the public portion of which was released in October this year, the U.S. identified China and Russia, as well as cooperation between those two countries, as the main threats to the international order and interests of the United States. However, the strategy treats China as the priority due to its economic and military potential. In the opinion of the Biden administration, Chinese policy threatens the stability of the Indo-Pacific, mainly via a potential attempt to take control of Taiwan by force within a few years. According to estimates by a number of American experts, this may happen as early as in the second half of this decade. Regardless of the accuracy of such analyses, they confirm the growing belief in the U.S. political elite that war with China is inevitable and that the United States’ participation is very likely. Therefore, the U.S. is tightening relations with the island’s authorities, including developing high-level political contacts, as exemplified by Pelosi’s visit, economic cooperation (in June this year, the partners launched the U.S.-Taiwan Initiative on 21st Century Trade), and military cooperation (arms supply and training for the Taiwanese military). Biden has also repeatedly suggested readiness to provide military aid to Taiwan in the event of an attack by China. At the same time, he declared that the U.S. had no offensive intentions towards China (e.g., during the talks with Xi at the G20 summit in Bali), and that it wanted to maintain the status quo, which was supported by the Taiwanese authorities.

The likelihood of the U.S. reacting to a possible escalation by China of actions towards Taiwan is deepened by the development of the Americans’ economic and defence cooperation with partners in the region. The U.S. has strengthened alliances with Japan and Australia, including through the Quad[7] (the three along with India) and new defence and economic cooperation forums, such as the AUKUS[8] defence agreement with Australia and the U.K. and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) oriented especially at ASEAN[9] partners.

For the EU, the assessment of China’s performance in the Indo-Pacific, especially with regard to a possible escalation against Taiwan, is based on different assumptions. Unlike the U.S., the EU does not recognise the military threat originating from China as a key element. According to the EU strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific[10] of September 2021, the region is of particular importance for the EU in terms of the economy, as well as in terms of maintaining the international rules-based order. The Union aims to diversify its supply chains, and its Member States are to increase their activity in the region in the field of security. Similar goals can be found in the Indo-Pacific strategies of individual EU members, including France from 2019[11] and Germany and the Netherlands from 2020. In the EU’s perspective, this approach is to facilitate the intensification of cooperation with regional partners, including ASEAN countries, which, like the EU, recognise the problems arising from relations with China, but at the same time want to continue cooperation with it, especially in economic areas.

Challenges for the EU

The direct consequence of the conflict over Taiwan for the EU would be the need to take action against China as a country undermining the rules-based order and international law (similar to the case of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine). Failure to react would run counter to the goals and values of the EU and would undermine relations with the U.S., which are key from the point of view of European security. And with the existing differences between the Member States regarding policy towards Russia, not countering China would dramatically reduce the EU’s rank as a globally important political entity. The challenge for the Union in this context is the expected retaliation[12] and economic blackmail from China, to which the EU is vulnerable given the strong EU-Chinese trade and investment ties[13]. Fears in EU countries about retaliation by China will make it difficult to reach consensus on imposing restrictions on it.

A decision by the U.S. and its allies to join the defence of Taiwan would trigger a regional conflict that would have serious consequences for the EU and would force a re-evaluation of relations with China. A possible conflict would cause serious disruptions in supply chains from Taiwan, China, and other Indo-Pacific countries, which as a result may lead to a shortage of many important products on the EU market (e.g., rare earth metals or microprocessors), blocking a large part of EU production, and thus complicating the situation of companies cooperating with partners from the Indo-Pacific. In the period of preparations for an invasion and progressive escalation, the investments and capital of EU companies present in China would also be threatened, which would be an element of Chinese pressure on the governments of the countries where these companies come from.

The EU’s dependence on China is based not only on its strong position as a supplier of selected components and products to the EU (e.g., machines or electronic equipment) but also on the discretionary and politically motivated creation of preferential conditions for functioning on the Chinese market for selected European companies. The growing interdependence of the Chinese economy and the EU’s, primarily Germany’s, is evidenced by, among others, an increase in the value of German investments in China in the period January to October 2022, during which it rose by more than 110% year on year. Recently, imports of products from the Chinese province of Xinjiang[14], where there are numerous reports about forced labour, have also increased. This applies to, among others, lithium batteries or solar panels sold to such countries as Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Poland, and France this year. China’s attempts to use economic ties to force political concessions (such as in the case of Lithuania[15] or Australia) suggests that this would also be the case for an expected EU response to the Chinese escalation against Taiwan. It would be highly probable that exports to the EU would be reduced in selected sectors, along with the introduction of restrictions and administrative difficulties on European companies operating on the Chinese market, possibly also including repression of foreign workers from these companies or EU citizens.

The EU and China are each other’s largest trading partners. In 2021, the value of exports from China to the EU amounted to more than €400 billion, while EU sales to China were over €270 billion. Most of the imported machinery and equipment to the EU are imported from China (electronics and telecommunications equipment accounts for over 50% of the value). A report by the Polish Economic Institute from September this year points out that the EU’s greatest dependence on China is in renewable energy sources (RES), electronics, the health sector, and energy-intensive industries (e.g., the chemical sector). Key EU imports from China include magnesium (93%), graphite (47%), light rare-earth metals (99%), and heavy rare-earth metals (98%). The EU is also a net importer of basic components for semiconductor production[16]—in this respect, China is its main trading partner, ahead of Taiwan and Japan. In 2019 and 2020, China accounted for more than 50% of the EU’s imports of diodes and transistors, and Taiwan was the most important exporter of integrated circuits to the Union. A situation in which China would be able to control the semiconductor sector in Taiwan (the world’s largest producer) or inhibit production would prevent the implementation of plans contained in the European Chips Act[17], among others.

China also uses the belief among some EU members (e.g., Germany, Spain, France, or Hungary) about the need to maintain cooperation with China to increase control over strategic branches of the economy and the information sphere in these countries. This applies to, among others, allowing Chinese companies to build and operate critical infrastructure (including ICT networks or energy), or increasing Chinese influence in education and information, including through cooperation with universities, investments in the publishing industry, or campaigns in social media.

The influence of China, and above all the EU’s economic dependence on China, means that the possibility of an effective and low-cost EU response to China’s escalation towards Taiwan (as well as a possible invasion) is currently very limited. However, failure to respond effectively would have consequences for the security interests of the EU. Therefore, in the face of possible aggressive actions by China against Taiwan in the coming years, the European Union should first of all take measures to limit such activity, support Taiwan and oppose China’s aggressive policy. It is also advisable to prepare a catalogue of responses in the event of a possible full-scale invasion scenario.

Such actions would meet the expectations of EU citizens. According to a survey published by the German Marshall Fund in September this year, in nine out of ten EU countries surveyed (Spain, Sweden, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Portugal, Poland, Italy, and Lithuania), the majority of citizens are ready to tighten their governments’ policy towards China, even if it would have a negative impact on the economy of these countries (among the surveyed EU members, supporters of this solution were in a minority only in Romania). In the event of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, the majority of respondents would support diplomatic action as well as the imposition of sanctions on China (with the exception of residents of Italy and Romania). Support for shipments of weapons to Taiwan is negligible (not exceeding 10%) in all the surveyed countries.

Recommendations for the EU

In view of the growing threat from China to the security of Taiwan (and the related destabilisation of the Indo-Pacific), it is in the EU’s interest to achieve four main goals: a) reducing the risk of a conflict, b) urgently reviewing relations with China, c) reducing long-term interdependence, and d) preparation of measures in the event of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, including possible sanctions.

a) EU actions in peacetime to respond to the escalating tensions around Taiwan to reduce the risk of war:

- EU should support Taiwan, including its presence in international organisations, through the development of diplomatic relations (in line with the “One China” policy) and economic relations. Intensifying contacts with Taiwan and expanding its group of partners would probably reduce the effectiveness of China’s escalation activities. China adjusts the level of escalation to the anticipated response of Western states. EU action should also include the development of Taiwan's defence capabilities, for example, by supporting its submarine programme and training public defence in cooperation with the U.S., also in relation to hybrid threats. The military activity of EU members in the Taiwan Strait should be taken into account, in accordance with the provisions of the EU strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, such as the movements of French or German warships.

- Consistent signalling by the EU, the U.S., and their allies (e.g., Japan) of their readiness to respond decisively to China’s escalation actions. Actions towards Russia, for example in the context of imposing sanctions on it for the invasion of Ukraine, can serve as a model in this respect. The continuation of joint assistance to Ukraine and the isolation of Russia are the reasons for these signals. The defeat of the Russian Federation (even if it does not result in the formation of a pro-Western government in Moscow) would complicate Chinese calculations regarding the takeover of Taiwan.

- Development of the defence potential of the EU Member States so that they are able to take over a greater burden of deterrence and defence against Russia in the European theatre. As a result, the U.S. could more credibly signal its readiness to fully engage in the defence of Taiwan, also in the event of a threat of a simultaneous escalation from Russia, which in turn could adversely affect the Chinese plans.

- Economic aid for Taiwan, for example in the event of a blockade of the island by the Chinese, or the imposition of extensive restrictions on the import of Taiwanese products by China. It could include, for example, preferences for Taiwanese producers in selected sectors.

b) Revising relations with China and reducing the EU’s interdependence with it in the short term:

- Highlighting the EU’s concept of relations with China as an increasing threat to the Union, instead of the formula of “partnership, competition and rivalry”. The pursuit of cooperation in specific areas, such as climate policy, rather than fostering the fulfilment of EU ambitions, leads more to the Union’s growing susceptibility to Chinese influence.

- Accelerate the implementation of instruments limiting China’s economic influence[18] in the EU. The decision-making mechanisms developed within them should give the European Commission effective powers to reduce the Union’s dependence on China. They may include an anti-coercion instrument[19], a ban on the import of products manufactured with the use of forced labour, an anti-subsidy instrument, etc., as well as extending the scope of existing tools, such as investment screening[20]. These also could include restrictions at the Union level on Chinese investment, especially in sectors with high levels of dependence and technological importance for the Union.

- Strengthening instruments for monitoring and counteracting Chinese disinformation in the EU[21] (including within the EEAS).

- Supervision of EU financing of cooperation with China by academic centres (development of a catalogue of “good practices”).

- Control of the functioning of Chinese media in the EU (modelled on the U.S. registration system).

- Conducting information campaigns on the costs of dependence on China in European societies.

c) Long-term reduction of the EU’s dependence on China:

- Greater involvement of the EU in the enforcement of standards and norms within international organisations, as well as preventing the election of Chinese citizens to managerial positions in these institutions. A good example was the cooperation with the U.S. in the election of the new secretary-general of the International Telecommunications Union in September this year as the successor to the current boss from China. The new secretary-general, who defeated the Russian candidate, is from the U.S.

- Broader cooperation and implementation of joint economic projects with the U.S., Australia, Canada, and Japan, as well as the introduction of legislation that takes into account the issues of economic security and dependence on China to a greater extent. One dimension of such action could be jointly funded projects, such as research.

- The use of programmes such as Global Gateway[22] not only as development or humanitarian aid, but above all as an instrument to strengthen economic security in connection with the threat from China.

- Development of storage systems for materials necessary for production, such as rare-earth metals or semi-finished products used in the electromobility sector. Introducing certain storage requirements for such materials in order to be able to maintain production for a specified period of time after a possible break or limitation of supplies from China.

- Collaboration with the U.S. within the Trade and Technology Council, including in limiting the supply of semiconductors to China by manufacturers from the U.S. and European countries, as well as the components and technologies used for their production.

- Diversification of trade and investment ties, including the development of cooperation with Taiwan or ASEAN countries, including through the finalisation of trade and investment negotiations conducted by the EU.

- Creating conditions that facilitate and encourage EU companies to relocate production from China to other EU countries or regions, including Central Europe, to increase the stability of supply chains, as well as the production and technological capacity in the Union.

d) Actions in the event of a possible attack by China on Taiwan:

- Preparation and consultations within EU countries, as well as other partners, including the U.S., Japan and Taiwan, of an appropriate response to the launch of offensive actions by China, including various scenarios of possible escalation and the EU response.

- Working out the foundations of a common political position in case of an attack together with the U.S., ASEAN partners, the UK, Japan, Australia, and South Korea and emphasising the illegal nature of the Chinese activities, support for Taiwan, and joint efforts to defend the international rules-based order.

- In the event of an attack, the adoption of a sanctions package that includes the above-mentioned elements limiting economic cooperation and having political consequences for China. They should include a common part (dependent on the scale and details of the Chinese escalation), including, for example, individual sanctions on Chinese politicians or officials responsible for making decisions involving Taiwan, and a flexible part (depending on the degree of escalation of the crisis by China), including restrictions in cooperation with companies from China involved in the arms industry and the production of dual-use products, suspension of broadcasting by Chinese media in the EU, and a ban on the participation of Chinese companies in EU-funded projects.

- The intensification of the military presence of some EU countries in the region, including in order to support possible U.S. actions or to secure transport routes and delivery chains.

[1] M. Przychodniak, “Prospects of Conflict in the Taiwan Strait, “ PISM Bulletin, no 113 (2030), 14 July 2022, www.pism.pl.

[2] Public opinion polls by National Chengchi University in Taiwan show that in September 2022, 7% of Taiwanese supported the possibility of unification with China, 30% favored the island’s independence in the future, and 57% believed that the current status quo is the best solution.

[3] J. Szczudlik, “U.S. Speaker of the House Visits Taiwan,” PISM Spotlight, no 112/2022, 4 August 2022, www.pism.pl.

[4] The Chinese army is currently undergoing modernisation, which, according to Xi Jinping’s announcements, is to be completed by the end of 2027, and concerns, among others, the development of naval potential (aircraft carriers), nuclear deterrence (construction of new silos for long-range missiles), and next-generation drones, all instruments necessary for the success of a possible invasion.

[5] M. Przychodniak, D. Wnukowski, „Challenges for China`s Economic Development in 2022”, PISM Bulletin, no 61 (1978), 13 April 2022, www.pism.pl.

[6] M.A. Piotrowski, “National Security Strategy: U.S. Focuses on Relations with Asia and Europe,” PISM Bulletin, no 162 (2079), 19 October 2022, www.pism.pl.

[7] P. Kugiel, D. Wnukowski,” The Quad Summit and New U.S. Economic Initiative— Strengthening Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” PISM Spotlight, no 93/2022, 27 May 2022, www.pism.pl.

[8] M. Piotrowski, „AUKUS: Australia, UK, and the U.S. Strengthen Defence Cooperation,” PISM Spotlight, no 73/2021, 21 September 2021, www.pism.pl.

[9] D. Wnukowski, „ASEAN in U.S. Foreign Policy,” PISM Bulletin, no 199 (1895), 24 November 2021, www.pism.pl.

[10] P. Kugiel, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific: Stabilisation Instead of Confrontation,” PISM Spotlight, no 71/2021, 17 September 2021, www.pism.pl.

[11] Ł. Maślanka, ““Global France”: The Significance and Consequences of Macron’s Policy in the Indo-Pacific,” PISM Strategic File, no 9 (101), October 2021, www.pism.pl.

[12] M. Przychodniak, „Regression and Pro-Russia Rhetoric: China’s Reaction to Lithuania’s Change of Policy,” PISM Bulletin, no 191 (1887), 16 November 2021, www.pism.pl.

[13] M. Przychodniak, „Problems Increasing in EU-China Relations,” PISM Bulletin, no 98 (2015), 14 June 2022, www.pism.pl.

[14] M. Przychodniak, “The Impact of the Repression in Xinjiang on China’s Relations with Other Countries,” PISM Bulletin, no 85 (1781), 22 April 2021, www.pism.pl.

[15] M. Przychodniak, „Regression and Pro-Russia Rhetoric: China’s Reaction to Lithuania’s Change of Policy,” PISM Bulletin, no 191 (1887), 16 November 2021, www.pism.pl.

[16] O. Szydłowski, „A Technological Arms Race: Chip Manufacturing,” PISM Bulletin, no 135 (1831), 16 July 2021, www.pism.pl.

[17] O. Szydłowski, „New Opportunities for the European Chip Industry,” PISM Bulletin, no 11 (1928), 21 January 2022, www.pism.pl.

[18] M. Przychodniak, „Problems Increasing in EU-China Relations,” op. cit.

[19] S. Zaręba, „The EU’s Search for a Response to External Economic Pressure,” PISM Bulletin, no 54 (1971), 6 April 2022, www.pism.pl.

[20] J. Szczudlik, D. Wnukowski, „Investment Screening Reforms in the U.S. and EU: A Response to Chinese Activity,” PISM Bulletin, no 1 (1247), 2 January 2019, www.pism.pl.

[21] A. Legucka, M. Przychodniak, „Disinformation from China and Russia during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” PISM Bulletin, no 86 (1516), 21 April 2020, www.pism.pl.

[22] E. Kaca, „The EU’s Global Gateway Strategy: Opportunities and Challenges,” PISM Bulletin, no 31 (1948), 17 February 2022, www.pism.pl.