Bulgaria Faces Political Uncertainty after New Early Elections

On 9 June, the sixth parliamentary election since spring 2021 was held in Bulgaria. Once again, the party Citizens for the European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) of former three-time Prime Minister Boyko Borisov scored the best result. He is likely to try to build a new governing coalition together with the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS). The formation of a new government centred on these parties would mean that Bulgaria’s pro-Western orientation and its support for Ukraine would be maintained, but it would not be conducive to internal reforms, particularly a more effective fight against corruption.

Stoyan Nenov / Reuters / Forum

Stoyan Nenov / Reuters / Forum

Why was there yet another early election?

The election followed the break-up in March of the grand coalition of the centre-right GERB and centre-left-liberal alliance of the We Continue the Change and the Democratic Bulgaria (PP-DB) parties. The coalition was an attempt to break the deep impasse in the Bulgarian political scene that has been in place since the parliamentary elections of spring 2021, the last one held by the constitutional deadline and after the mass anti-corruption protests of 2020. These undermined Borisov’s narrative, until then effective, that the only alternative to his pro-Western, albeit corrupt, rule was the takeover of the government by pro-Russian post-communists and nationalists. The voter mobilisation that followed the protests resulted in new anti-establishment parties emerging and winning seats in parliament. They promised to settle GERB to account, but quickly lost support in the face of their inability to meet this demand and deliver stable governance.

How will the composition of the Bulgarian parliament change?

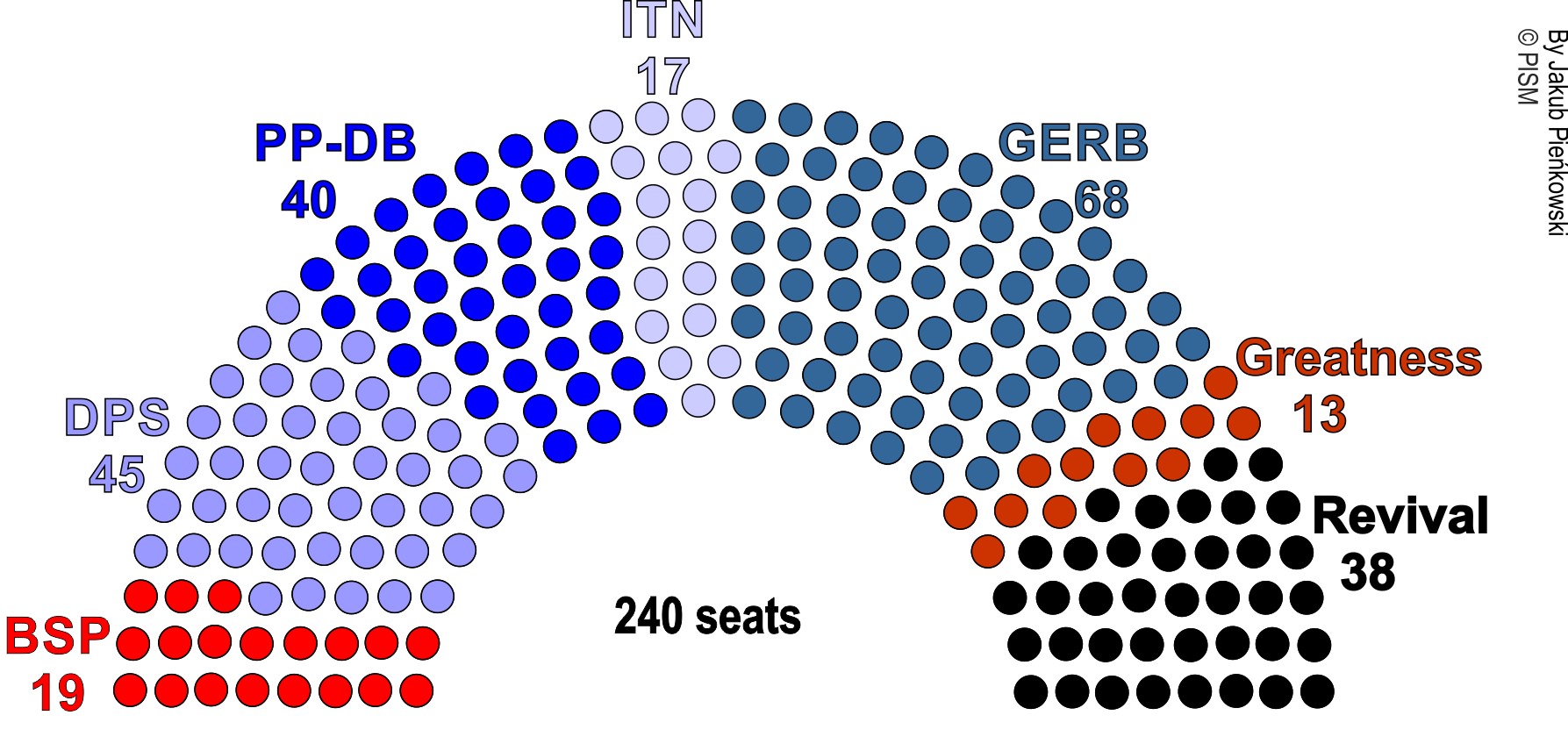

This vote had the lowest turnout in Bulgaria's post-communist history, at 32.5%, despite the elections being held alongside those for the European Parliament, which favoured parties with a disciplined electorate. As a result, GERB remains the strongest in the 240-seat National Assembly (25% of the vote and 68 seats, -1 than before). It is followed by DPS, the centrist Turkish minority party, effectively controlled by oligarchs, which became the second-largest faction for the first time (17%, 45 MPs, +9). The pro-Russian and nationalist Revival (14%, 38 seats, +1) and the eclectic and populist party There Is Such a People (ITN; 6%, 17 seats, +6) also achieved better results. New to parliament is the Greatness party, which originates from the local government of the small Vetrino municipality and holds nationalist and Eurosceptic views; it also advocates strict neutrality in the war in Ukraine (5%, 13 seats). The PP-DB alliance, which was the second force in the past term, lost the most voters, who were disillusioned by its cooperation with GERB and lack of spectacular reforms (14.5%, 40 seats, -24). The post-communist and pro-Russian Bulgarian Socialist Party also lost ground (BSP; 7%, 19 seats, -4).

Will there be a regular government?

The formation of a regular government approved by parliament in the usual way will be hampered by the limited coalition capacity of the parties. Borisov announced his readiness to form a cabinet together with the DPS (which would give the coalition 113 seats). This faction declared its willingness to enter government and even name a prime minister; these two parties have been informally cooperating for years, cultivating corrupt-oligarchic arrangements in local and central governments. Borisov, however, is making the formation of a coalition conditional on the entry of a third partner to secure the majority. PP-DB has rejected the possibility of co-forming a government, promising instead to be the “hard opposition”. Revival offers support for a coalition, but makes demands that are impossible to meet by the unequivocally pro-Western GERB and DPS , including stopping aid to Ukraine and abandoning efforts to adopt the euro. BSP and ITN declare their readiness to support an expert government. Greatness, on the other hand, wants to support only selected projects in parliament. Dragging out the coalition negotiations is likely given the lack of precise deadlines in the constitution for the formation of a government. According to it, the president, Rumen Radev, will entrust the mission of forming the cabinet to the strongest party, GERB. In case it fails, then he will hand the mission over to the second-place DPS, and then to any party at his discretion. In the case of failure to form a government, he will call another election, which at this moment cannot be ruled out.

How will the election results affect Bulgaria’s foreign policy?

Until a regular government is formed, the country will be led by the technical cabinet of Dmitar Glavchev, the GERB-linked president of the Bulgarian National Audit Office. This cabinet pursues a pro-Western policy, but the implementation of reforms is hampered by the lack of stable support in parliament. The formation of a government centred on GERB and DPS would ensure the continuation of Bulgaria’s pro-Western policy, as these parties support closer European integration, cooperation in NATO and with the U.S., modernisation of the army, and military aid to Ukraine. The entry of DPS into the cabinet could help overcome the crisis in relations with North Macedonia, as it was the only party in the National Assembly to criticise the Bulgarian veto blocking that country’s European Union membership negotiations between 2020 and 2022. At the same time, a government of GERB and DPS, embroiled in structural corruption, could only offer simulated reforms to combat it. This, in turn, could heighten the caution of EU partners, Austria and the Netherlands, as well as others, who are sceptical of Bulgaria’s aspirations and delay its entry into the eurozone and the Schengen area by land as well, not just by air and sea, which Bulgaria obtained in March 2024.

Figure 1. Distribution of Mandates in the Bulgarian National Assembly after the Elections in June 2024.

(1)_sm.jpg)

.jpg)