Armenia-Azerbaijan Peace Talks Yield Little Results

The peace talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan that resumed after the end of fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh last autumn did not result in the signing of a peace treaty. They were bilateral, as Azerbaijan did not agree to mediation again by Russia, the EU, or the U.S. The lack of progress in the talks to reach at least the signing of a treaty partially regulating relations between the two countries may encourage Azerbaijan to forcibly impose its own solutions on Armenia.

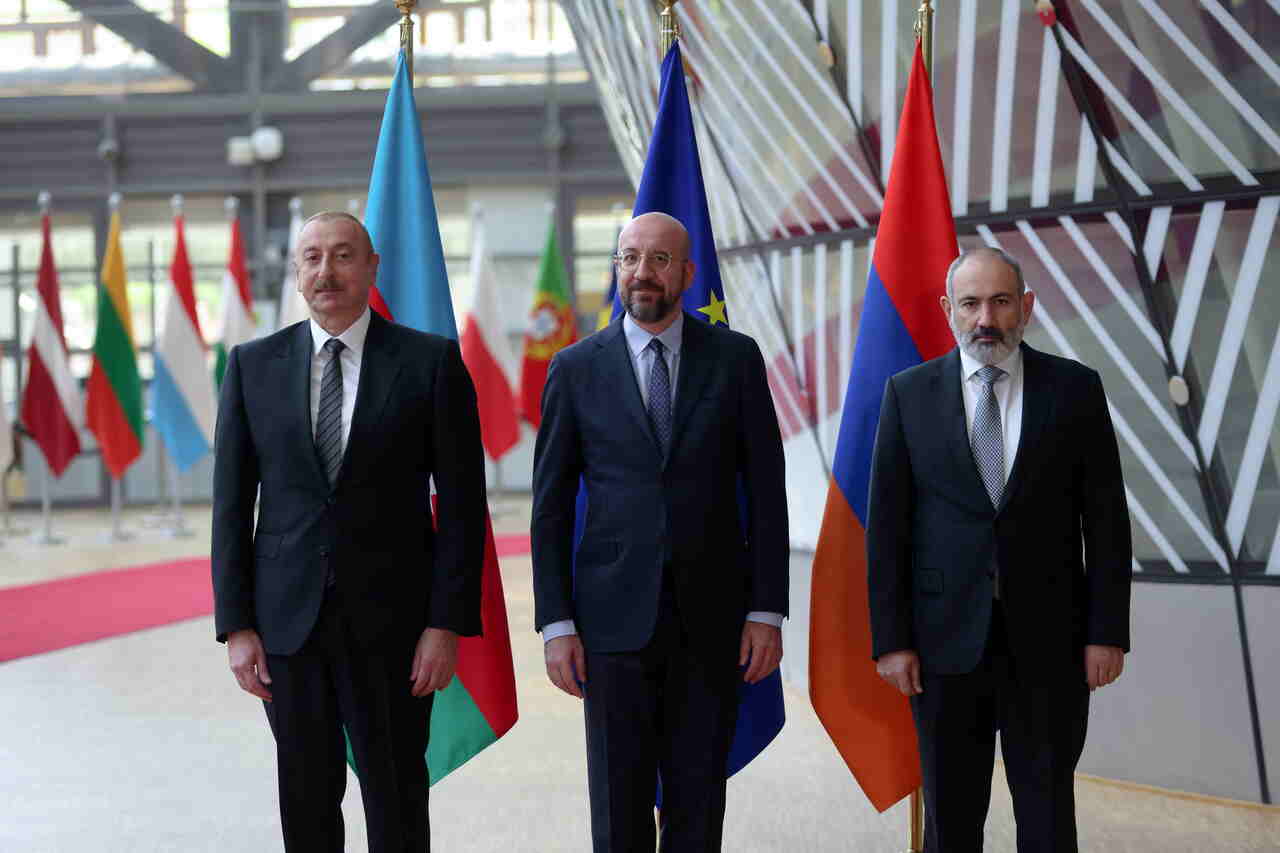

JOHANNA GERON / Reuters / Forum

JOHANNA GERON / Reuters / Forum

After nearly three decades of Armenian control over Nagorno-Karabakh (NK) and the so-called occupied territories, Azerbaijan regained sovereignty over two-thirds of the disputed territory in 2020 as a result of the Second Karabakh War. Following the end of the active phase of the conflict, the parties started peace negotiations (November 2020-September 2023). However, these talks failed to make progress and, last September, Azerbaijan decided to launch a renewed military operation, as a result of which it finally regained full control over the NK.

New Format of Talks and Contentious Issues

After regaining NK, Azerbaijan initially froze and then resumed bilateral talks with Armenia, but already in a different format. After its military success, Azerbaijan’s position was strong enough to force Armenia to negotiate, this time without intermediaries, such as Russia, the EU, and the U.S., which it accused of using mediation to strengthen its own political position in the region. President Ilham Aliyev refused to meet Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan on the margins of the European Political Community summit in Granada last October, and a few days later, on the margins of the Commonwealth of Independent States summit in Bishkek. Weakened militarily and politically (there were demonstrations in Yerevan calling for Pashinyan to step down as prime minister), Armenia agreed to Azerbaijan’s terms.

Despite NK’s return to Azerbaijani sovereignty, several issues still remain to be resolved between the two sides. In the ongoing negotiations, the parties are discussing the following contentious issues: (1) mutual recognition of territorial integrity; (2) demarcation and delimitation of the border; and (3) the unblocking of transport routes, including the so-called Zangezur transport corridor that connects Azerbaijan with its exclave Nakhichvan, and further to Turkey and Europe.

Successes and Failures of Bilateral Talks

On the delimitation of the border, the parties were still unable to reach a final compromise (with the exception of four Azerbaijani villages, which Armenia agreed to hand over to Azerbaijani control). Talks were also held through informal channels at a lower level. The Armenian-Azerbaijani committee on demarcation and delimitation of the border has met several times. At the same time, both the Armenian prime minister and the Azerbaijani president declared that an agreement was close. For Armenia, the basis for the delimitation of the border with Azerbaijan is the 1991 Alma-Ata Declaration, according to which the borders of the states created by the breakup of the USSR should be defined on the basis of the borders of the former Soviet republics. Azerbaijan, on the other hand, refers to maps from before the creation of the USSR.

Nor has there been any progress in the talks on transport corridors. Armenia opposes Azerbaijan’s demands to make the so-called Zangezur corridor extraterritorial. It stresses that it agrees to opening the route subject to full control over it. At the same time, Pashinyan put forward an alternative proposal to the Azerbaijani demands last autumn, which would be to open the Armenian borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan, which have been closed since the First Karabakh War (1992-1994). All states in the region would be able to use roads and rail links with their neighbours on the basis of reciprocity and equality, but they would remain under the jurisdiction of the entity on whose territory they are located, ruling out any extraterritoriality of routes. However, Pashinyan’s proposal did not meet with a positive response from Azerbaijan and Turkey.

Under pressure from Azerbaijan, the Armenian prime minister agreed to amend the Armenian constitution and delete the passage from the preamble stating that Armenia’s goal is unification with the NK. Fearing that Azerbaijan would again resort to the option of force, in January this year Pashinyan offered Aliyev to sign a declaration to renounce the use of force in settling issues of concern, withdrawing its troops from the border region and mutual arms control. Azerbaijan rejected this proposal. The Armenian authorities are constantly concerned about a renewed conflict with Azerbaijan, as evidenced by Pashinyan’s alarmist statements in February and March this year announcing an Azerbaijani attack on Armenia on the occasion of his visits to France and to four villages located in the Armenian province of Tavush, which the Azerbaijani side is demanding to return.

External Actors

In the Armenian-Azerbaijani dispute, Azerbaijan can count on the full support of Turkey. Armenia, on the other hand, can count on the favour of Iran, which strongly opposes the creation of the so-called Zangezur extraterritorial corridor, fearing the strengthening of Turkey and Azerbaijan in the region, as well as the disruption of trade with Armenia and Russia. The Iranian authorities stress that the unblocking of transport corridors must not come at the expense of violating the territorial integrity of the South Caucasus states.

The other external actors—Russia, the EU, and the U.S.—do not take sides in the dispute, and their aim remains to help Armenia and Azerbaijan (declaratory in the case of Russia) to reach an agreement. An attempt to overcome Azerbaijan's reluctance to involve the EU in the negotiations was made by Germany. On the margins of the Munich Security Conference in February this year, Chancellor Olaf Scholz organised a meeting between Pashinyan and Aliyev. Several days later, talks between the foreign ministers of the two countries took place in Berlin. However, the meetings did not result in a breakthrough.

Conclusions and Prospects

The ultimate solution for Armenia and Azerbaijan to their problems is the signing of a treaty comprehensively regulating relations between the countries, which would lead to the unblocking of transport routes in the region, the opening of borders and the establishment of diplomatic relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Armenia would emerge from more than 30 years of blockade in the region, which would have a positive impact on its development opportunities. It also would be a personal success for Pashinyan, who would strengthen his political position despite losing the war. Azerbaijan and Turkey, on the other hand, would gain the opportunity to intensify trade with China, Central Asian countries and Europe. The position of Russia, on the other hand, would be weakened in the region, as its military presence, both in the NK and Armenia, would become irrelevant due to the final settlement of the conflict (on 17 April this year, the Russians announced that they were withdrawing their troops from NK, originally their mission was due to expire at the end of 2025). The Russians are interested in opening the so-called Zangezur corridor and installing FSB officers there. In addition, they would also like to see a change of power in Armenia from Nikol Pashinyan to a pro-Russian government. Currently, however, this scenario seems unlikely due to the parties’ differing positions on the so-called Zangezur corridor.

At present, only a treaty partially regulating relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan is possible, with an emphasis on mutual recognition of territorial integrity. The issue of the demarcation of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border and the unblocking of communication routes would become the subject of further negotiations. The treaty would provide a security guarantee for Armenia from Azerbaijan and could envisage a conditional opening of Armenia’s borders with Azerbaijan and Turkey and the establishment of diplomatic relations, although it would not resolve significant issues of contention. At the same time, a resumption of limited fighting by Azerbaijan to force further concessions on Armenia remains a viable alternative to peace talks.

The EU may consider pressuring Azerbaijan to agree to return to talks with Armenia with the EU as mediator, which would increase the likelihood of preventing a possible renewal of the conflict. The EU could threaten Azerbaijan with sanctions should it again seek to resolve the conflict with Armenia by force. It is in the EU’s interest to maintain peace in its immediate neighbourhood and unhindered trade routes, including energy supplies. Furthermore, in order to build its position in the post-Soviet area, the EU, including Poland, may decide to strengthen its relations with Armenia by increasing the size of its civilian mission in the country (currently numbering 209), tasked with monitoring the Armenian-Azerbaijani border, supporting Armenia in controlling its borders with Iran and Turkey, providing it with multi-year funding under the European Peace Facility, or supporting Armenian energy reform. The EU may also consider negotiating with Armenia on visa-free travel or eventually granting Armenia candidate status for EU membership. Increased EU activity would be a way out of Armenia’s efforts to change the direction of its foreign policy from pro-Russian to pro-Western.

.jpg)

.jpg)