Prospects Dim for Settling the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Despite the intensification of talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan on settling the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, no breakthrough has been achieved. The leaders of the countries, respectively, Nikol Pashinyan and Ilham Aliyev, declare their willingness to reach an agreement, but have not come to terms on any major issue. The future status of Nagorno-Karabakh, guarantees for Karabakh Armenians, and the course of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border remain unresolved, raising fears of a renewed war.

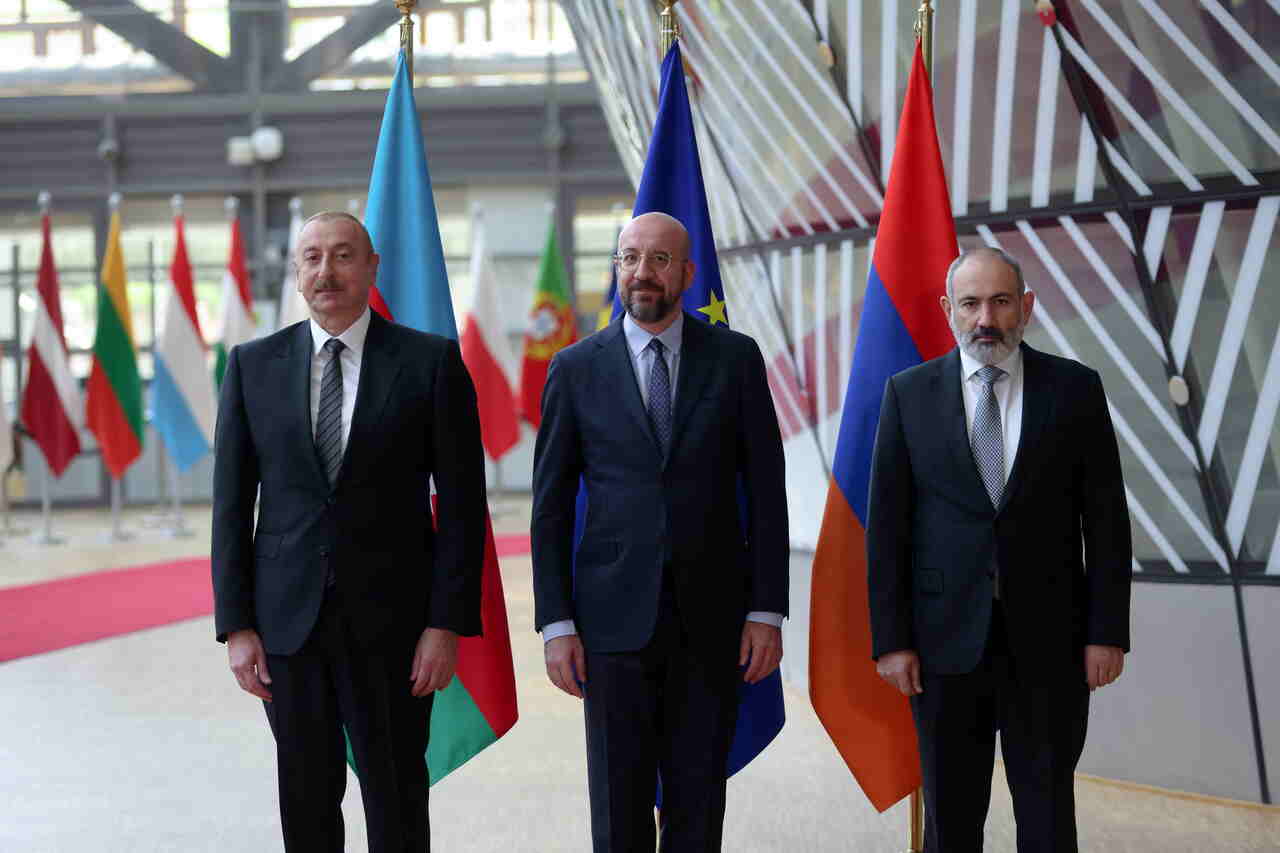

JOHANNA GERON/Reuters/Forum

JOHANNA GERON/Reuters/Forum

In recent months there have been dozens of meetings between Armenian and Azerbaijani representatives in Washington, Moscow, Brussels, and Chişinău. The talks were attended by Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, as well as the foreign ministers of both countries. The aim of the negotiations is to conclude a comprehensive peace treaty to regulate mutual relations after the Second Karabakh War in 2020, which ended decisively in Azerbaijan’s favour. The talks are accompanied by irregular exchanges of fire on the Azerbaijan-Armenia border and in Nagorno-Karabakh. All the while, there is a serious risk of the Azerbaijani side resuming the conflict and seizing the rest of the Armenian-controlled territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Contentious Issues

A key issue in relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan is the future status of Nagorno-Karabakh. In the spring of this year, the Armenian prime minister announced that he recognised Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan, a move that met the expectations of the other side and could lead to a breakthrough in negotiations. However, the declaration was accompanied by a condition that Azerbaijan grant special security guarantees for Armenians there. This demand was opposed by the Azerbaijani president, who stressed that Karabakh Armenians are Azerbaijani citizens and will have the same rights as other citizens, a position opposed by Armenia. Pashinyan’s concession was due to his awareness of Armenia’s extremely weak position after losing the war, and, because he wasn’t born in Karabakh, a lack of emotional attachment towards the issue. The negotiations were thus aimed at achieving the best possible results under unfavourable circumstances.

The demarcation and delimitation of the Azerbaijan-Armenia border remains a problem. The course of most of it was not demarcated after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The parties rely on different maps—Armenia on a 1975 USSR General Staff map, while Azerbaijan bases its interpretation on various 20th-century maps. On some of them, Armenia's southern province of Syunik and Yerevan belong to Azerbaijan. An element of the disagreement remains the return of refugees to the Armenian-controlled Nagorno-Karabakh area. At issue are Azerbaijanis who left the region in question as a result of the First Karabakh War (1992-1994). Their return could lead to social tensions stemming from disputes over land and home ownership, compensation for lost property, as well as a desire for revenge against Armenians for injustices suffered 30 years ago.

The blockade of the so-called Lachin corridor connecting Armenia with parts of Nagorno-Karabakh also casts a shadow over the talks. Until recently, it remained under the supervision of Russian soldiers under an agreement ending the 2020 war. The road was blocked last December by Azerbaijani so-called eco-activists, who allegedly spontaneously started protesting against illegal Armenian exploitation of natural resources in Nagorno-Karabakh. In reality, the Azerbaijani side’s aim was to cut off the supply of food, medicine, and transportation of Karabakh Armenians for treatment in Armenia in order to induce the Armenian authorities to make concessions. In Armenia’s perception, this has triggered a humanitarian crisis that is expected to result in Armenians leaving Karabakh. In recent weeks, Azerbaijan has banned International Red Cross trucks from entering the area in question, accusing its employees of supplying weapons and smuggling alcohol and cigarettes. Calls to Azerbaijan to open the link, made by Armenia but also by the U.S., the EU, Russia, and the International Court of Justice, have so far failed to yield results.

The unblocking of transport routes in the South Caucasus region, including the so-called Zangezur transport corridor, intended to connect Azerbaijan proper with its exclave Nakhichevan via Armenian territory, also remains a subject of dispute. Under the November 2020 agreement, traffic on this section is to be supervised by Russian border guards. After the Second Karabakh War, Azerbaijan insisted that it should control the transport route, making it a de facto extraterritorial corridor.

Local Context

With the peace process underway, the leaders of both states are under political pressure in their respective countries. Prime Minister Pashinyan is under attack from the opposition, centred on the former presidents Serzh Sargsyan and Robert Kocharian, over his policy, portrayed as appeasement. Also sceptical of the negotiations led by the Armenian prime minister is the Armenian diaspora, which plays an important political and financial role in the conflict. Moreover, the actions of the Armenian authorities are viewed reluctantly by Nagorno-Karabakh’s political elite, who expect to be included in negotiations with Azerbaijan.

In Azerbaijan, both members of the power elite and the public itself are waiting for a solution to the Nagorno-Karabakh issue, understood as taking total control over it. President Aliyev cannot afford to make significant concessions to Armenia. Karabakh’s reintegration would minimise the risk of a popular revolt stemming from frustration over authoritarianism and post-pandemic economic problems, and would diminish the opposition’s arguments in its criticism of the authorities.

International Context

Mediation in the peace process is offered constantly by the EU and the U.S., which are appealing to Azerbaijan to unblock the Lachin corridor. Their goal is to comprehensively resolve the disputes between Armenia and Azerbaijan and to ensure the security of Europe’s natural resource supply routes independent of Russia. Late last year, the EU sent a civilian mission to Armenia to stabilise its border areas, ensure the safety of people in conflict-affected areas, and provide conditions conducive to the normalisation of Armenia’s relations with Azerbaijan.

Russia, which was supposed to be the guarantor of compliance with the truce after the Second Karabakh War, is interested in freezing the conflict and maintaining its influence in the region. Given its involvement in the war in Ukraine, however, it is now less able to play a leading role in Nagorno-Karabakh. At the same time, it does not want to lose control of the situation in the region, which is why it is responding to U.S. and EU actions by holding parallel negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Moscow.

Both Armenia and Azerbaijan accuse Russia of not properly fulfilling its peacekeeping mandate, the formal task of which is to monitor the implementation of the ceasefire. According to Azerbaijan, they are unable to block smuggling and arms supplies to Karabakh, while Armenia blames them for being passive in the face of the blockade. In the fall of 2025, the five-year deadline for their stationing in Nagorno-Karabakh expires. Their presence may be extended, but this has been opposed by the president of Turkey, a country that is a traditional ally of Azerbaijan. Iran, on the other hand, will not allow cutting off transit routes to Armenia, which could threaten the opening of the Zangezur corridor, under Azerbaijani control.

There is also growing scepticism on the part of the Armenian authorities about Russia’s attitude toward settling the conflict. They point to a lack of response by the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) to Azerbaijan’s attacks on Armenian territory. In late May this year, Prime Minister Pashinyan did not rule out Armenia’s exit from the CSTO and “discussing security issues with other potential allies”.

Conclusions and Prospects

Achieving peace in Nagorno-Karabakh now seems a distant prospect despite the intensification of talks between Armenia and Azerbaijan. This is mainly due to the inflexible position taken by Azerbaijan (blockade of the Lachin corridor, refusal to grant not only political but even linguistic and cultural guarantees to Karabakh Armenians, and the desire to control the transport corridor to Nakhichevan). The parties have failed to reach a compromise on any key issue. Azerbaijan is acting from a position of strength as the winner of the 2020 war and one that can resume military operations at any time. It will be able to count on supplies of military equipment from Turkey. Armenia is also rearming by purchasing weapons from India, among others.

An Armenian-Azerbaijani agreement envisaging the granting of de facto sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan would be met with resistance from much of the Armenian population, the Armenian diaspora and Armenians living in Nagorno-Karabakh. The protests could lead to the removal of Armenia’s prime minister from power and torpedo the peace process. An intermediate option is also possible, essentially working out a partial agreement, including, for example, the unblocking of the Lachin corridor by Azerbaijan in exchange for Armenia’s agreement to open transport routes under the joint aegis of Russian, Armenian, and Azerbaijani border guards.