After the EP Elections, Majority Likely to Pursue Minor Course Corrections

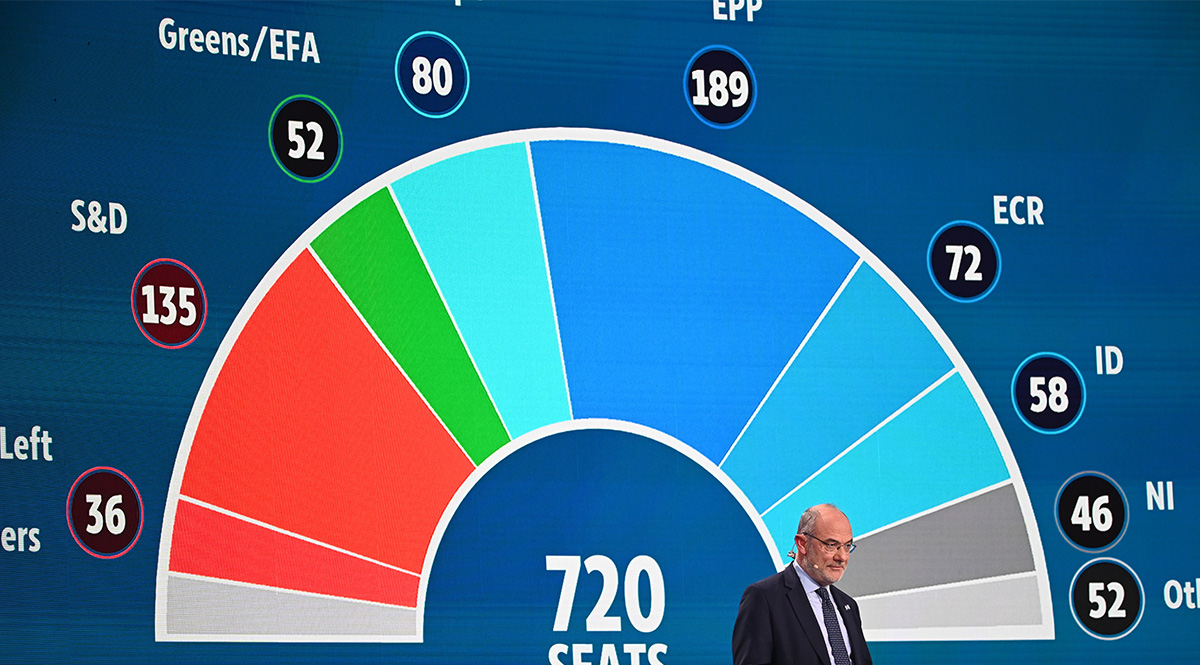

Following this spring’s European Parliament (EP) elections, the three centrist parties—Christian Democrats, Socialists, and Liberals—again have an absolute majority. Their grouping, the European People’s Party (EPP), which won the most votes, has moved to the right of centre since the end of the previous term and will predominantly decide the priorities of the future European Commission (EC). The far-right has also strengthened, and it will be important for its role in the coming term which political groups, existing or new, its MPs join.

Alessandro Di Meo / Zuma Press / Forum

Alessandro Di Meo / Zuma Press / Forum

Centre Weakened but Stable

After the EP elections, the centrist parties hold the absolute majority of around 55% of all seats. The most likely scenario, therefore, is the re-emergence of an informal coalition in support of the future EC made up of the EPP, Socialists and Democrats (SD), and Liberals from Renew Europe (RE). However, its formation is more difficult than in 2019. The total number of MEPs of these parties is lower compared to the previous legislature (when they had 60% of all seats) mainly due to the worse result of RE and (to a much lesser extent) the losses of SD. In addition, the final shape of the political groups that will form in the Parliament is still uncertain, for example, the Czech party ANO already announced that its MEPs will leave RE and remain non-aligned, at least for the time being.

One of the main sticking points in the negotiation of the new EC’s priorities will be the extent and pace of implementation of the European Green Deal (EGD). Since the end of the previous legislature, the EPP has been changing its attitude to this sphere of EU legislation—it tried to prevent the adoption of the Nature Restoration Law, and before the elections decided not to proceed with legislation on restrictions on the use of pesticides, among others. The party argued that the overly ambitious implementation of the EGD could discourage voters, and consequently lead to parties opposed to its introduction taking power. In addition, it tightened its stance on migration issues (advocating, for example, the creation of centres outside the EU to which asylum seekers would be sent).

For the SD and RE, on the other hand, the continuation of ambitious EGD policy is an important element of their political agendas and they will seek to ensure its consistent implementation. To weaken the EGD, the Christian Democrats may seek temporary alliances with other groupings. Although the EPP leadership denied the possibility of a more formalised alliance, it did not rule out ad hoc cooperation on specific legislative projects with parties belonging to the right-wing European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group. Such declarations, however, aroused opposition from, among others, the SD. The Socialists announced that during the upcoming negotiations, they will seek a written commitment from the EPP not to enter into such alliances.

Strengthened Right-Wing

Right-wing and far-right parties gained compared to the previous term. In addition, the exit of Fidesz (currently 10 MEPs) from the EPP and the expulsion of the AfD (currently 15 MEPs) from the Identity and Democracy (ID) group in the previous legislature means that there are a significant number of non-aligned MEPs with a similar ideological profile. They could seek to join one of the parliament’s right-wing groups or form a new one, but the threshold for the formation of one is relatively high (23 MEPs representing at least seven countries). Some ECR parties (e.g., Law and Justice) have spoken positively about admitting Fidesz into their group’s ranks, but this has been met with internal resistance, including threats to leave (e.g., from the Czechs and Swedes). Since the acceptance of the Alliance for the Union of Romanians into the conservative group, Fidesz has coarsened its tone and is sceptical about the possibility of joining the ECR.

The creation of a larger group that would unite all right-wing and far-right parties in the EP is of interest to, among others, Marine Le Pen of the French National Rally (RN)—MEPs from this party make up more than half of the ID. The formation of such a super-group would be another step towards mainstreaming the image of the RN. Le Pen has been pushing for such a change in the perception of her grouping for a long time. However, a similar alliance would face internal opposition within the ECR. A more likely scenario, therefore, is the formation of a new political group—according to Der Spiegel, for example, discussions are currently taking place regarding the formation of a faction called “The Sovereignists”. This would include members of the German AfD, the Polish Konfederacja (6 MEPs), Spain's Se Acabó La Fiesta (3), and Romania’s SOS (2).

Top Jobs

The distribution of key positions in the EU will depend on the establishment of a common framework of cooperation between the informal coalition supporting the future EC. Ursula von der Leyen has the best chance of being re-elected EC president. She is most likely to win the required qualified-majority vote in the European Council (at least 20 Member States representing 65% of the population), but it may be more challenging to gain a similar level of trust in the EP. Although the three centrist parties hold about 400 seats in the EP (the legal majority is 361), their members will not vote unanimously for the party’s nominee (especially as the vote is secret). Negotiations on the priorities the Commission will include in its EU policy proposal for the next term will therefore be key.

The other top roles to be negotiated are the president of the European Council (this will most likely be taken by Portugal’s former Socialist Prime Minister António Costa) and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (this role will most likely be filled by Kaja Kallas, the current prime minister of Estonia, whose party is part of the RE). The most likely candidate for another 2.5-year term as EP president is, on the other hand, the Maltese Roberta Metsola of the EPP. Once it has been decided who will hold these positions, negotiations will follow on the positions of the commissioners, which is mainly decided by the Member States.

Conclusions and Outlook

Although the number of MEPs belonging to the three groupings forming the informal coalition in the previous legislature has decreased, this does not threaten the majority they hold in the EP. The EPP strengthened its position and the RE saw the biggest losses, which will translate into a stronger pursuit of the Christian Democrats’ political priorities in this legislature. The party has recently moved to the right of centre and will seek to bring about a correction of important EU policies. This is especially true for the EGD (lesser penalties for non-compliance with standards, more incentives), but also for migration issues (more restrictive policy). This will create friction with its main partners, but the EP will continue the main policy lines developed by the EC in the previous term, including the decarbonisation policy for EU economies. However, the pace of its implementation may be much slower than initially planned, and the tools used to do so less stringent, although also likely arousing less public resistance.

The strengthening of right-wing parties creates a favourable negotiating situation for the EPP in the new EP. This is because it means that they will support any proposals by the Christian Democrats that weaken the EGD or tighten migration policy, in case they do not find support from their existing partners. Unlike the EPP, on the other hand, the alternative left and centre-left forces are unable to form even ad hoc majorities with which they could seek to block legislation they consider unfavourable. In an attempt to prevent such a situation from arising, they will try to obtain a written commitment from the EPP that would limit the grouping’s ability to cooperate with right-wing parties, but the chances of these attempts succeeding are not very high.

The constitution of a majority in the EP and the associated new institutional cycle creates opportunities for Poland to obtain positions that will allow it to pursue its priorities in European politics in a meaningful way. These include both the likely new position of defence commissioner and enlargement commissioner or one of the important economic portfolios (with a possible position of EC vice-president). Poland should also endeavour—also within the framework of regional cooperation—to obtain other functions crucial from the point of view of its interests and the security situation in the region, filled by persons who will represent a similar sensitivity on issues of importance to the country. These include, above all, an assertive policy towards Russia, support for Ukraine, and strengthening the transatlantic alliance.