Centre Still Holds after the European Parliament Elections

The European Parliament (EP) elections on 6-9 June were won again by the European People’s Party (EPP). Centrist forces maintained their majority in the EP and will once again form the informal coalition supporting the European Commission (EC). This will start a new institutional cycle and entail changes in important EU positions, including the key one of the EC president.

Aleksiej Witwicki / Forum

Aleksiej Witwicki / Forum

What were the election results?

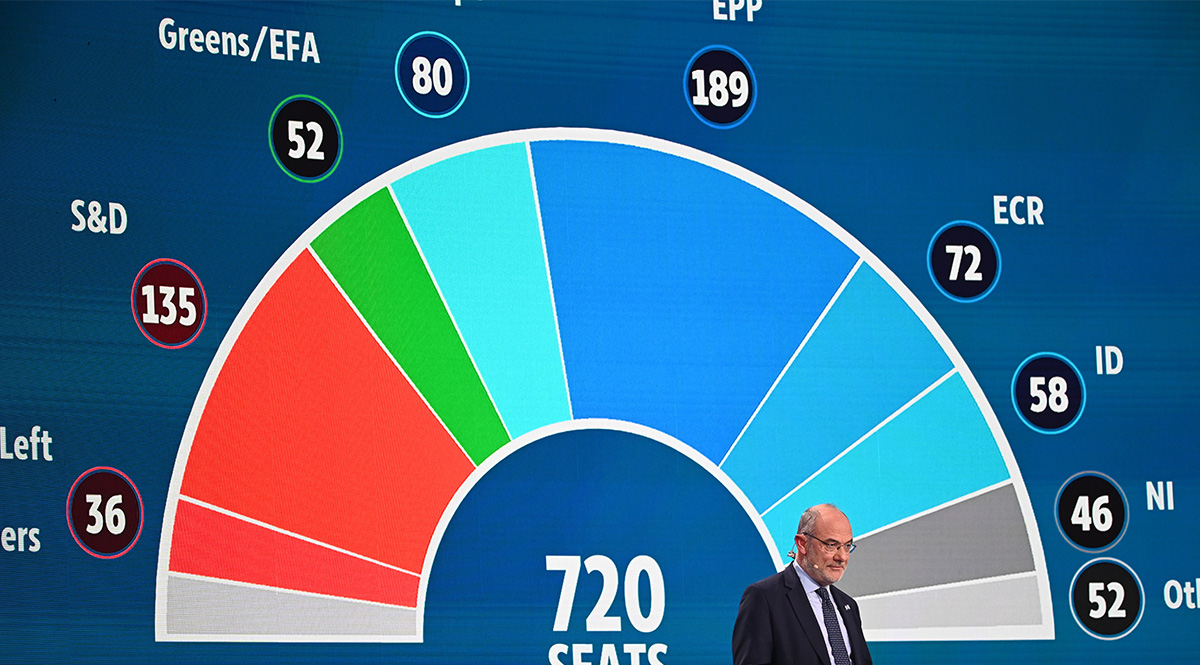

By a decision of the European Council of September 2023, the 10th European Parliament was increased from 705 to 720 seats to better reflect the population of the Member States. According to initial projections, the largest party of the new EP will remain the Christian Democrat EPP, which will receive 186 seats (its share of the overall seat pool increased by 0.9 percentage points compared to the previous term). Second and third place, respectively, went to the Party of European Socialists (PES), with 135 seats (down by 1 p.p.), and the Liberals, in the previous legislature grouped in the Renew Europe (RE), with 79 seats (down by 3.5 p.p.). Right-wing and far-right groups strengthened. The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) gained 73 seats (up 0.4 p.p.) and the far-right Identity and Democracy (ID) gained 58 seats (up 1 p.p.). The Greens weakened (52 seats, down 2.6 p.p.) and, although to a lesser extent, also the Left (36 seats, down 0.2 p.p.).

What do the results mean for the functioning of the European Parliament?

The three largest parties have an absolute majority of around 55% of all seats in the EP, but this is a regression from the previous Parliament when the figure was almost 60%. Developing a common position will also be more difficult due to growing resistance within the EPP to, among other things, the introduction of ambitious Green Deal standards (the PES and the RE continue to emphasise the need for strong implementation).

The increase in support for far-right parties was less than forecast—throughout the year, ID remained in the polls in the 80-90 range of expected seats. What weakened this group the most, however, was not a decline in public support, but the removal from its ranks of nine Alternative for Germany (AfD) MEPs in May of this year. In the current election, AfD increased its numbers and will most likely receive 15 seats (they will sit as independents for the time being).

What will be the composition of the main political groups in the new Parliament?

The European political parties will now form political groups in the EP. Depending on their size, they will be allocated funds, important administrative and political functions in the Parliament, and speaking time in debates. In the previous EP, there were significant changes in the composition of the groups (apart from the expulsion of AfD from ID, Fidesz left the EPP and PES suspended the Slovakian parties belonging to this political family), which will have a bearing on their formation after the current elections. The least certain is the shape of the right-wing groups—some parties in the ECR (e.g., Poland’s Law and Justice, PiS) would like to see Fidesz in their ranks, but this raises objections within the larger group, including threats that some members would withdraw from it if this were to happen (announced by the Czechs and Swedes, among others). The far-right ID will in turn be weakened by the absence of the AfD, which was the third-largest national representation in the group in the previous term. The large number of far-right party MEPs who do not belong to any of the existing political groups also creates the potential to create another group with this profile, although the threshold is relatively high—23 MEPs from seven different Member States are needed.

How will the results translate into the composition of the EU’s key institutions?

The new institutional cycle means changes to key EU posts. Ursula von der Leyen still has the best chance to return as EC president. However, she first must be approved by a qualified majority in the European Council (where the support of the Member States for her candidacy is likely to remain) and then by an absolute majority in the EP. In the previous parliamentary term, her candidacy won a slim majority of only nine votes (while the groups supporting her had 60% of the EP’s seats); this may now be more difficult not only because of the smaller majority in parliament (55%) but also because of opposition to her candidacy from some parties within her parent EPP (e.g., the French Republicans announced during the campaign that they would not support her). The vote is secret, which further favours von der Leyen’s opponents, as there are no consequences for deviating from the party line. In the absence of a majority for her candidacy from her existing allies, it is possible that the incumbent EC president will seek support from right-wing parties (e.g., Giorgia Meloni’s grouping).