Tensions in China-Sweden Relations: Conclusions for the EU

Causes of the Dispute

The deterioration of bilateral relations stems from Sweden’s criticism of China’s human-rights policy and violation of the norms of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations of 1963. The main reason for the dispute is the case of Gui Minhai, a Swedish citizen born in China (after the events of 1989 in China, he renounced his Chinese citizenship and adopted Swedish citizenship). He is one of Hong Kong’s booksellers selling publications critical of the Chinese authorities. In 2015, he was detained in China, then released in 2017 before being imprisoned again in 2018. Chinese state television twice broadcasted his confessions—most likely under pressure—in which he said that Sweden was using his case for political purposes. China does not recognize Gui Minhai as a Swedish citizen, making it difficult for Swedish diplomats to access him, which they consider a violation of the Vienna Convention.

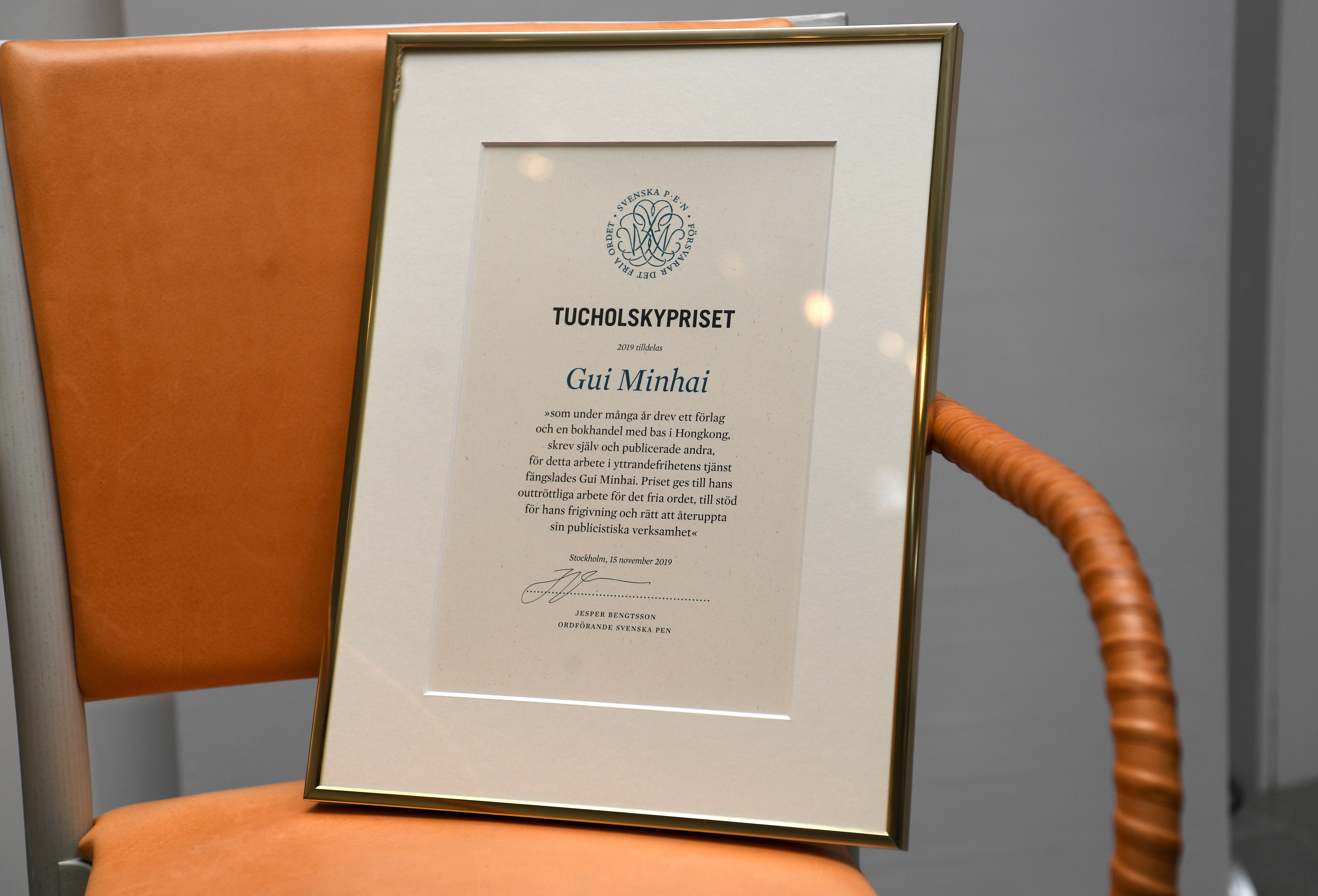

The dispute escalated in December 2019 when the Swedish PEN Club awarded Gui Minhai its Tucholsky Prize for his actions in defence of free speech, and the minister of culture of Sweden took part in the ceremony. China’s ambassador to the country publicly warned the minister that her presence at the ceremony could result in her refusal of entry to China, and later he announced restrictions on economic cooperation with Sweden. The Chinese MFA described the award as “unacceptable interference in Chinese internal affairs” and demanded an apology from the culture minister before dialogue would resume. The screening of several Swedish films in China and the arrival of two business delegations to Sweden were cancelled.

Earlier, in 2016 in Beijing, the authorities detained and eventually expelled from China Peter Dahlin, who was working with a Chinese NGO on legal education. Another reason for the deterioration of Sino-Swedish relations was the Swedish support expressed in October 2019 within the UN General Assembly’s human rights commission, together with 23 countries, criticising China for its repression of the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang.

China’s Motivation and Instruments

The rejection of human-rights criticism by China and the authorities’ sharp reaction in the Gui Minhai case are aimed at maintaining the government’s image as the defender of China’s reputation. By opposing Sweden’s actions in defending one of its own citizens, the Chinese authorities are ignoring international law (in this case, the Vienna Convention) while demanding that other countries accept China’s interpretation of human rights in cases such as Gui Minhai’s. The Chinese authorities are trying to stop international criticism of issues that they believe undermine the monopoly of the Chinese Communist Party’s power or China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Such topics include matters related to the situation (i.e., repression) in Xinjiang or Tibet. When such criticism occurs, China threatens sanctions and accuses the other party of interfering in its internal affairs. They have used threats against other countries, such as the Czech Republic or in 2010, against Norway after Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Among the informal sanctions that followed caused, for example, Norwegian salmon’s market share in China to fall from 90% to below 30%. Relations were only stabilised in 2014 after the Norwegian government publicly recognised China’s outrage over the prize as justified.

The instruments of pressure are usually informal. These include the cancellation of cultural events or high- and mid-level visits. The functioning of companies from a given country in China is also limited, for example, by discouraging Chinese partners from cooperating with them. The increased restrictions (from strong rhetoric and verbal accusations to restrictions on the import of human rights goods) are intended to accelerate a policy change in a given country. The sooner the country admits to an error, the sooner it is possible to normalise the relationship.

Sweden’s Reaction

China is Sweden’s most important trading partner in Asia. In 2018, the value of exports to China amounted to more than €6 billion and Chinese imports were more than €7 billion. So, Sweden is trying to balance and moderate critique of China’s human-rights policy. However, it will not waive its demand for Gui Minhai’s release.

In trying not to further escalate the dispute, Sweden is not interested in Gui Minhai’s case being directly addressed by EU institutions in talks with Chinese authorities. This is probably why High Representative Josep Borell did not mention the case during the first meeting with Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, in December 2019. The Swedish side hopes that quieting the case will help reduce Chinese retaliation. At the same time, this issue means that some Swedish local governments (Vara municipality, city of Gothenburg) have decided to review their cooperation with their Chinese counterparts, even considering the termination of partnership agreements. The Swedish government’s conciliatory approach to China is criticised by the opposition, which may increase its determination.

Conclusions

The pressure on Sweden is part of China’s policy positioning towards the European Union ahead of the EU-China summit in March and the autumn “China+27” meeting in Leipzig (with heads of state or EU heads of government and Xi Jinping). In this way, China wants to strengthen its negotiating position, strongly signalling the pursuit of favourable EU decisions, for example, on 5G. On one hand, China suggests its readiness to cooperate, for example, by starting work on an EU-China free trade agreement, and, on the other, Chinese ambassadors use threats against European countries, arguing that they are defending China’s interests, such as ensuring the participation of Chinese companies in building 5G or its right not to comply with international human rights standards. This has been seen in the Czech Republic when Prime Minister Andrej Babiš assessed as credible the warnings from Czech security services about the threats arising from cooperation with China, and in Denmark when the fate of Huawei’s participation in the construction of 5G in the Faroe Islands was in the balance. The behaviour of Chinese ambassadors is also due to the desire to demonstrate zeal before the leadership of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs; in January 2019, Qi Yu, an official with no international experience but previously an important CCP Central Committee politician, was appointed the “first” deputy minister.

Due to the position of the Swedish government, the current dispute will be subdued and any Chinese repercussions will not be severe. This example shows that China’s determination depends in part on the categorical nature of the allegations, the weight of the subject of the dispute, and the political level at which they are formulated. This is, among other things, why China’s negative response after the detention of a Chinese Huawei employee in Poland or the signing of a joint Polish-American declaration on 5G from September 2019 was limited. The document suggests Poland is excluding Chinese companies from participation in the construction of the 5G standard, but representatives of the Polish administration assured that they would not prohibit any entity from participation in this project. This allowed China to further still emphasize the possibility of Huawei's participation in 5G in Poland and in the EU.

China’s pressure on the Member States is also often calculated to undermine the European Commission’s China policy. Therefore, the EC should—in accordance with its “EU-China Strategic Outlook” from March 2019—openly signal disagreement with Chinese actions directed at the EU, including it as part of ongoing economic negotiations. It can exploit, among others, China’s willingness to finalise the “EU-China Investment Agreement” in 2020 and readiness to strengthen cooperation with the EU in the context of the strategic rivalry with the U.S. Any suggestion of specific decisions regarding 5G, for example, by Chinese diplomats in the Member States should result in official complaints to China’s MFA. One novel solution may be the announcement by the High Representative, who announced mapping the provisions of the so-called Global Magnitsky Act in the EU system, that is, introducing sanctions on individuals responsible for the policy of human rights violations, such as authorities and others in Xinjiang.