State of Emergency and Record Economic Stimulus Package in Japan

What is the status of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan?

By the end of March, there were few coronavirus infections in Japan’s population of 126 million—an average of tens of new cases per day. The situation changed at the beginning of April. The number of infected doubled in the last five days to more than 4,800 people, including more than 700 infected on the Diamond Princess cruise ship that docked in the port of Yokohama in February. There have been 108 deaths. The largest increase in infection was reported in the regions of Kanto (including the metropolitan prefecture of Tokyo), Kansai (including the urban prefecture of Osaka), and the Fukuoka prefecture. Experts are unable to determine the reasons for the increase in infections in these areas.

Why and in what prefectures did the government of Japan introduce a state of emergency?

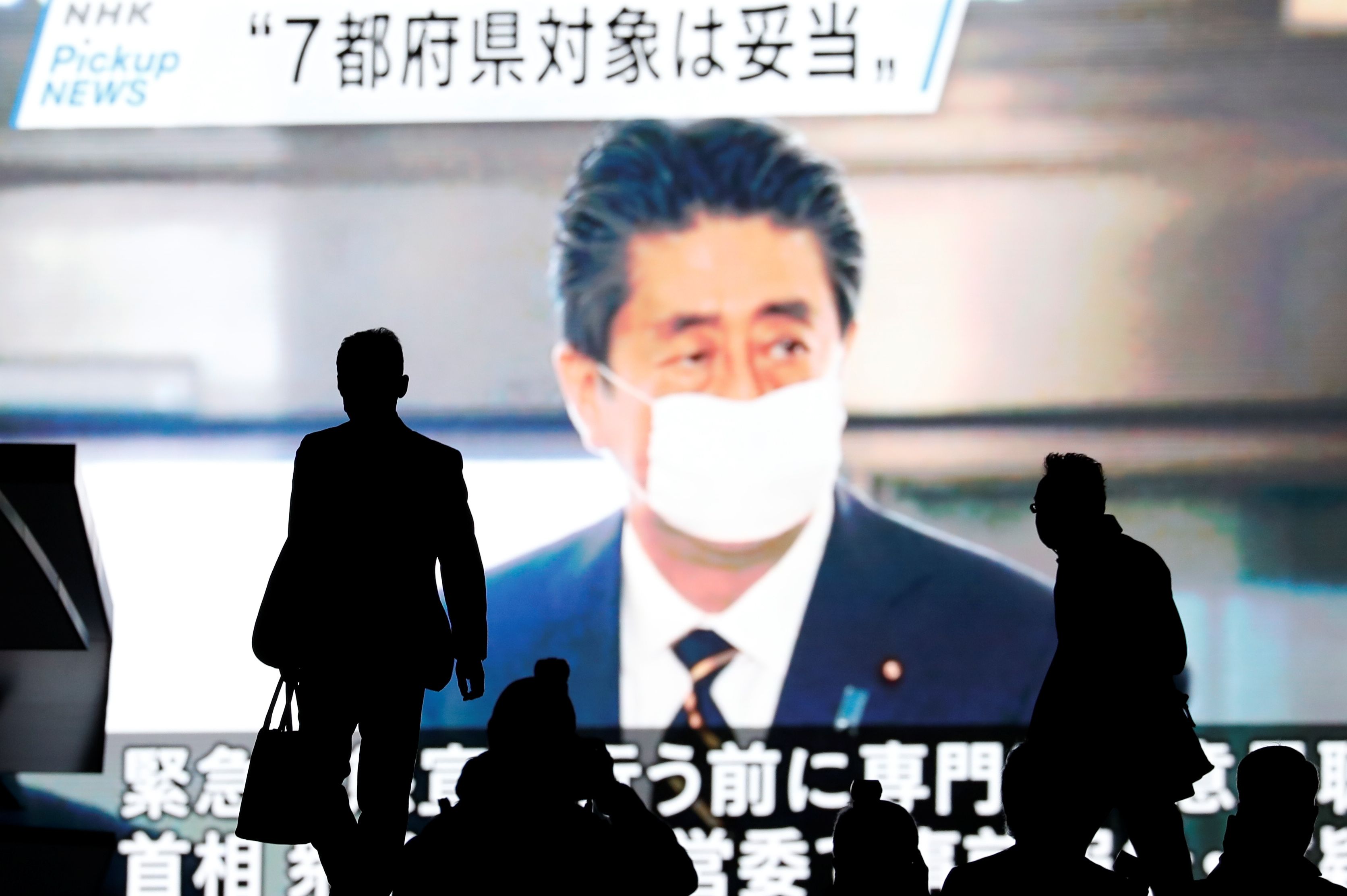

Prime Minister Abe cited the growing likelihood that the increase in COVID-19 cases will seriously threaten the health and life of citizens, as well as harm the country’s economy. This meets the requirements necessary to introduce a state of emergency in accordance with the related legal act amended last month. The prime minister’s decision was influenced by, among others, the governors of Tokyo and Osaka, who appealed to the government to declare an emergency. It allows the governors to enact restrictive measures to prevent the spread of the virus. Moreover, the medical services indicated that without additional restrictions there is the high probability of multiplying the number of infections in the coming weeks and overloading the healthcare system. The state of emergency will last until 6 May and includes the seven prefectures most affected by the pandemic—Tokyo, Osaka, Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Hyogo, and Fukuoka. These states are also crucial to Japan’s economy and are inhabited by about 45% of the country’s population.

What does a state of emergency mean in Japan?

The governors of the affected prefectures may require people to stay at home. Citizens may leave their residences only when necessary to do their grocery shopping, commute to work, or go to the hospital. Local authorities may also recommend closing selected stores, schools, and public places, such as cinemas. Prime Minister Abe appealed for the introduction of remote working as widely as possible and to limit contact across the country. Although Japanese law does not provide legal penalties for noncompliance, the authorities are counting on the traditional compliance of citizens with the recommendations. If the situation worsens, the local authorities may expropriate private property (e.g., hotels) for use in the fight against the coronavirus, medical supplies, or food from companies refusing to sell it.

Why did the Japanese government introduce the stimulus package and what does it assume?

Last year’s consumption tax increase and the effects of the U.S.-China trade war contributed to a decline in Japan’s GDP to an annualised 7% in the last quarter of 2019. The pandemic has halted production in many Japanese automotive factories and forced the rescheduling of the Olympic Games, all of which could lead to a recession. The government’s reaction is an unprecedented large stimulus package of about $990 billion, which corresponds to about 20% of Japan’s GDP. Fiscal expenditures are to amount to about $360 billion. They will include cash transfers to households whose incomes have fallen by more than half and an increase in child allowances. The government will also subsidise small and medium-sized enterprises whose revenues have fallen by at least half. A total tax exemption is anticipated for companies whose sales have declined by more than 50%, but it will cost about $240 billion. Moreover, $130 billion of the package is intended to absorb the tripling of the national stockpile of Avigan, an antiviral drug used to treat 2 million people.

How will the state of emergency affect Japan’s economy and its investments in Poland?

The state of emergency and the increased expenditure under the stimulus package will deepen the problems of the Japanese economy. This will cause a likely decrease in consumer spending and, consequently, a slowdown in manufacturing activities. Many Japanese companies such as those in the automotive industry intend to reduce employment in factories in other parts of the world, including Europe. This can hinder Japanese investments in Poland—already in the second half of March, some companies (e.g., Toyota factories in Lower Silesia) suspended production. Japan may also reduce interest in new investments, including the infrastructure and energy sectors, which Abe discussed with Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki during the Polish government leader’s visit to Tokyo in January this year.