Russia’s Political Offensive in Africa

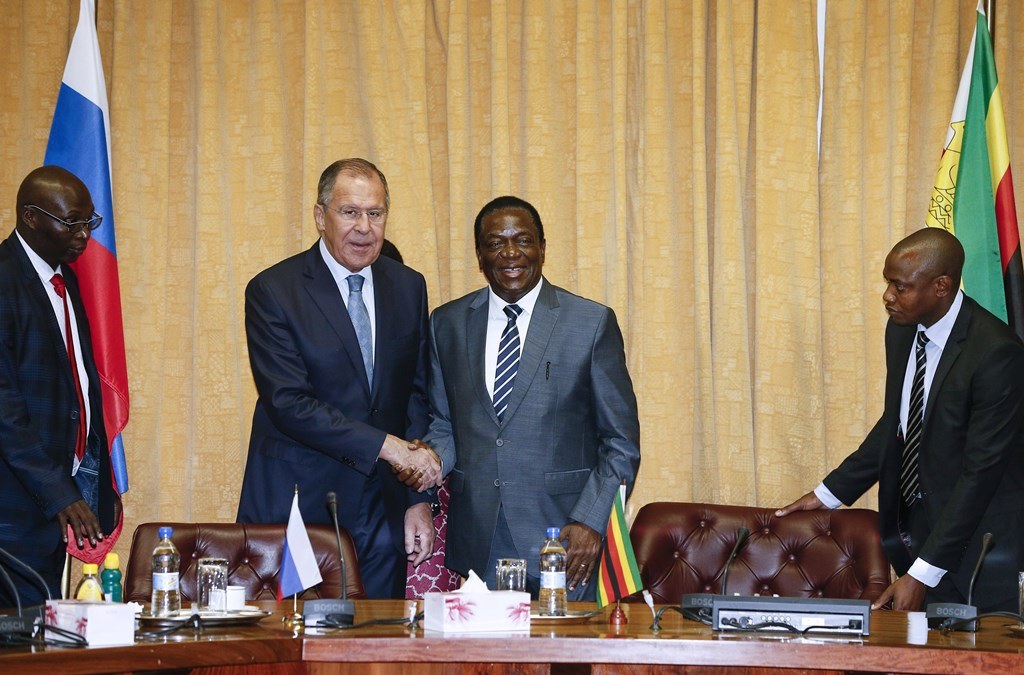

The turn of 2017 and 2018 brought departures of long-standing leaders of some key African states, including Zimbabwe, South Africa, Angola and Ethiopia. This new context renewed international focus on Africa where traditional influencers (the U.S. and the EU), emerging powers (China) and newcomers (Turkey, the Gulf States and Russia) seek advantages. The March 2018 African tour by Sergey Lavrov, Russian minister of foreign affairs, highlighted the growth of importance of the country’s African agenda. As he visited Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Ethiopia, Russia’s trade with sub-Saharan Africa was on a steady rise. It had already grown from $2.2 billion in 2015 to $3.6 billion in 2017,[1] although still represented only some 0.6% of its global trade.

This year is expected to bring a record high as Russia’s efforts to gain footholds on the African continent are accelerating, and a more coherent Africa policy is taking shape. Months before Lavrov’s trip, in a highly publicised move, President Vladimir Putin wrote off $20 billion of African debts. In the past this tool was used, on a smaller scale, to prepare the ground for new arms deals (Libya and Ethiopia), to expand Russia’s influence in countries with limited bilateral relations (Benin), to access new promising markets (Zambia) and to obtain exploration rights (Guinea).

Simultaneously, African leaders have become frequent visitors to Moscow. The inauguration of Putin’s renewed term on 7 May 2018, was attended by an unusually high number of the continent’s heads of state, including the presidents of Sudan, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia and South Africa. Russia plans to host the first high-level Russia-African Union (AU) summit in 2019, similar to EU and Chinese meetings with their African partners, and a business forum. Before that, Russia will seek to establish a comprehensive vision for its economic, security and diplomatic relations with Africa, covering state-to-state affairs and the AU dimensions. In March, Lavrov declared Russia would intensify scientific exchange and cooperation with the AU in combating terrorism and organised crime. In the latter respect, it would seek observer status in the AU Mechanism for Police Cooperation (AFRIPOL). It already supports the AU military mission to Somalia.

Characteristics of the Russian Approach in Africa

In 2017, new dynamics and new tools elevated the profile of Russian policies in Africa. These policies combine efforts to rebuild networks of relations decomposed after the fall of the Soviet Union with aggressive economic steps, based on seizing chances for quick political and economic gains in risky environments. The push for Africa is a manifestation of the broadening range of Russia’s foreign policy radar. After Syria, the continent became a crucial testing ground in Russia’s efforts to regain a global position.

The Cold War era produced a number of wide-ranging engagements and partnerships between the USSR and African states. Apart from several North African states, Ethiopia, Angola and Somalia hosted Soviet military facilities. The Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow and other high schools across the Soviet Union hosted approximately 25,000 African students before 1990. Among them, there were future presidents of South Africa, Mozambique and Angola. Radio Moscow had an African service. But the fall of the Soviet Union took Africa off the agenda of its successor, the Russian Federation. The bases were vacated, and many embassies were closed. The most significant remaining bond was arms sales, as Russia emerged in the 1990s as one of the key providers of armaments to the continent’s markets. After 2010, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for some 3% of Russia’s global arms sales (11% if Arab Northern African states are added). As much as 35% of African countries’ armaments imports come from Russian suppliers, mainly Rosoboronexport.[2] Russian equipment remained a desirable commodity due to its relative simplicity, price and the fact it is known on the ground due to Soviet-era experience. Also, it finds its ways to conflict zones more easily and with less moral doubts than arms coming from the EU or the United States. Apart from arms deals, a significant troop contribution to UN peacekeeping missions was instrumental in building relations in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Liberia, Sudan, South Sudan, Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia and Eritrea. Russia currently seeks to establish permanent bases on the continent, primarily in the Horn of Africa. In 2017, it tried to rent part of the Chinese-held plot in Djibouti to bring its own military facilities, but the host country blocked the deal under pressure from its U.S. and EU allies.[3] After that, Russia turned to Sudan. President Omar al-Bashir announced during his visit to Moscow in November 2017 that Russia could establish a base on its Red Sea coast, but later scaled down the offer to a “naval supply centre,”[4] possibly similar to the one Sudan discusses with Turkey.[5] It is also likely that Russia would approach Eritrea and Somaliland with similar requests. Establishing even a minor permanent military facility would be symbolic. It would confirm Russia’s recognition of the strategic importance of some parts of the continent for its wider international strategy.

While the pace of Russia’s speedy push for Africa is being compared to that of China, in many aspects the Russian approach is substantially different. For China, the military dimension comes last, after economic and people-to-people ties (including diasporas) are solidified. That was the case of establishing a base in Djibouti, a key Horn of Africa port already connected to the region’s interior with a Chinese-built railway. Russia would rather start with military cooperation as a means to win the gratitude and confidence of governments who struggle with legitimacy or have limited options for international cooperation. They, in consequence, would introduce Russia to those business sectors in which it could win some advantages over traditional powers, such as the U.S. or France. These sectors may include private security, nuclear technologies or access to rare mineral sites. As with the CAR before, the DRC was approached in this way in May 2018, when Russia made a revived military cooperation agreement proposal. Apart from arms sales, such a proposal would include the arrival of military advisors and the exchange of staff. As the ongoing political crisis in the DRC pushed the United States, the EU and its Member States, including former colonial power Belgium, to scale down relations and aid commitments, the Congolese leadership saw Russia as an attractive alternative. Russia, in return, is expected to obtain favourable conditions in the mining, energy and agriculture sectors.[6] The 2017 sale of fourth-generation Su-35 fighter jets to Sudan came with a similar package that included training. An additional promise of 1 million metric tons of grain[7] for developing cultivation could possibly establish Russian agricultural projects similar to those already in place in Senegal. A military cooperation agreement signed in 2018 with Guinea-Bissau, the first one since the demise of the USSR, falls into a similar scheme.

While sanctions keep Russian heavy industry out of the EU, the country mastered the ability to make a rapid entry into Africa once opportunities arise. In 2015, Rostec was commissioned to build a $4 billion oil refinery to serve Uganda’s newly discovered oil fields. Eritrea’s recent emergence from isolation, boosted by July’s rapprochement with Ethiopia, sent a signal that the country was open for political and economic cooperation. Immediately after the country’s government spoke of the need to build a new export port to serve an Australian-commissioned potash mine, Russia’s Lavrov welcomed top Eritrean diplomats to Sochi.[8] On August 30, they agreed to let Russia develop the new port into its logistics centre.[9] The U.S. and the EU, supportive of the political process in the region, ended up being late with economic entry, as high-level business contacts were long frozen by sanctions and the country’s grim reputation. Other major Russian industrial investments on the continent include a $3 billion platinum mine in Zimbabwe and the development of massive diamond deposits at the Luaxe mine in Angola. Both countries are undergoing political and economic transitions, and dealing with them requires skilled diplomacy and leverage to outmanoeuvre competitors.

With the development of ties to Russia, some of Moscow’s African partners increasingly adopt an anti-Western narrative. The 2017 meeting between Putin and Bashir was accompanied with strong anti-American statements by the Sudanese. This was surprising due to Sudan’s ongoing rapprochement with the United States. The U.S. was at that time in the process of lifting most of the economic sanctions, in place for the last 20 years. But the remarks were consistent with the Russian official position on supporting a “multipolar world.” In many African states, it is seen as somehow natural given the cult of the anti-colonial struggles, the bad experience of the IMF/World Bank push for structural reforms in the 1990s and the desire for the continent to have permanent representation at the UNSC. The notion resonates particularly among leaders and factions whose legitimacy is disputed and whose human rights records are poor, as it offers them a new rationale, one of participating in a global, ideological confrontation. Just as Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad does.

Use of Syrian Experience in Africa

Russia’s intervention on behalf of al-Assad’s government boosted its international image as a capable player and helped achieve a politically and economically privileged position in Syria. Lessons learned in Syria were later applied to Africa. The most visible one is extensive use of the private military contractors acting on a semi-official ticket.[10] After shadowy paramilitary units such as the Wagner Group first emerged in eastern Ukraine, they relocated to Syria where an important part of their effort was dedicated to securing oil fields regained from the Islamic State. Wagner was reportedly promised a 25% share in revenues from the oil and gas production from fields its units captured. Russia seems to replicate a similar business model in Africa, as paramilitaries end up close to extraction facilities in conflict areas. Private contractors from the RSB-Group first appeared in Libya in 2016 and stayed there until February 2017. Their arrival coincided with Russia’s policy of supporting general Khalifa Haftar, leader of the self-declared Libyan National Army, who effectively controlled most of Eastern Libya and claimed rights to rule the country.[11] In November 2016, he was received in Moscow with a hero’s welcome. Then, in early 2017, his injured fighters received treatment in Russia. Contractors were reportedly tasked with clearing mines from oil facilities captured by Haftar from Islamist forces. Their leader, Oleg Krinitsyn, referred to their role as independent of that of the Russian government but confirmed he was “consulting” about contractors’ moves with the Foreign Ministry. On the ground, local, pro-Haftar militants seemed to see Russian operatives as more welcome than other foreigners.[12] October 2018 brought reports of the arrival of Wagner mercenaries to Libya, allegedly accompanying Spetznaz forces.[13]

In late 2017, the first indications that Wagner Group operatives were on the way to Sudan emerged.[14] In subsequent months they were reported to be assisting Sudanese special forces in training, although the scope of their missions in the country still remains unclear. Sudan’s internal conflict zones (South Kordofan, Blue Nile and Darfur) are relatively quiet and no “anti-terrorist” offensive that could justify foreign engagement is on the horizon. Instead, it is likely that the mercenaries might have been hired to secure small gold mines, the most rapidly expanding and cash-effective industry in the country. Russia’s interest in the gold-extraction industry on the continent is on the rise. Nordgold, Russia’s major producer, recently expanded operations in Burkina Faso and other countries.[15] After Sudan lost most of its oil fields to South Sudan when the latter seceded in 2011, it focused on gold production as a means to replenish the treasury. A number of players, including former insurgents, transboundary criminal groups and pro-government militia, as well as the Rapid Support Forces, are involved in the competition for control over the newly discovered gold deposits. Bashir could be eager to strengthen his control of the income flows at the expense of sharing a portion of the profits with Russia and granting Moscow some influence on the way the country navigates in the delicate regional security setting. Russian mercenaries could also be instrumental in securing the expansion of the remaining oil deposits in the unstable southern borderland, especially Bloc E57, or the Jebel Moya area in North Kordofan, where Rus Geology is contracted to conduct geological mapping. Also, a December 2017 military build-up on the border with Eritrea might have played a role in the government’s renewed quest for battle-hardened allies. Having them onside could discourage eventual foreign incursions. As demand for translators and fixers grew rapidly with the arrival of contractors, Russia started to revive local networks of Russian-educated Sudanese, a move to be continued in different parts of Africa.

In the CAR, contractors from the Wagner Group came together with military experts in early 2018 to boost capacities and the legitimacy of President Faustine Touadera and to secure on the ground the business ventures of oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin. The group’s alleged patron, who reportedly controls Lobaye Invest, a company heavily involved in the extraction of rare minerals in the CAR, is trusted by Putin. Wagner personnel were seen using their armoured trucks to bring mining equipment to Lobaye sites.[16] By mid-2018, there might have been more than a thousand Russian mercenaries in the country.

Similarly to piloting the Astana peace talks for Syrian factions, Russia tries to play the role of peacemaker in Africa. In August 2018, it sponsored a round of peace talks between factions in the CAR’s conflict in Khartoum, Sudan. They involved Maxime Mokom’s Anti-Balaka forces and former Séléka rebels under Noureddine Adam. The talks were a parallel format to the African Union peace process, which have long been stalled. Despite the fact that the CAR’s government abstained from the Khartoum meeting, as did many other factions, and although participants committed themselves to supporting the AU process as the prime means of achieving peace, Sudan, with Russian support, continued the effort.[17] From the Russian point of view, it could play a similar role to Kazakhstan in Syria. As a country with diplomatic experience and regional leverage, it has the potential to achieve some settlements on the ground while keeping Western involvement at a distance. For Russia, the peace process itself, bringing together some anti-government factions which hold mineral deposits on their territories, could be instrumental in obtaining privileged access to new mining opportunities. With Sudanese ports used by Russian companies for the export of diamonds and gold from the CAR and Sudan, a new CAR-Sudan security axis, supplemented with Russian military contractors on the ground, would guarantee safe passage.[18] The next rounds of talks in Khartoum, to which France and regional leaders are invited, will indicate whether Russia’s plans are realistic.

Finally, as in Syria, a fresh approach to social media-driven propaganda and disinformation is reportedly being tested to help shape sentiments and discourage rivals. In the CAR, Russian media experts are said to have arrived together with military contractors and geologists – which would not be surprising due to Prigozhin’s involvement in running the St. Petersburg “troll factory.”[19] They are said to be behind some of the anti-French media and social media coverage and provocations. The latter included French flags being hoisted by unknown men in the contested PK5 area of the capital Bangui,[20] a largely Muslim neighbourhood and a former rebel stronghold, in a move aimed at boosting anti-French sentiment.

Case Study: The Central African Republic and Russia

Of its new engagements in Africa, the one in the Central African Republic brought the most spectacular rise of Russia’s role in a specific country. It is a particularly important case, as Russia quickly outmanoeuvred more experienced and powerful competitors in the CAR. The first signals of renewed Russian interest in the CAR coincided with a deepening of French and UN fatigue over involvement in the country whose 2012 civil conflict took on an intercommunal, religious dimension. France, which sent troops to the CAR in 2013, became increasingly frustrated with the continued political stalemate on the ground as CAR territory remained effectively divided between the armed factions. It withdrew its forces in October 2016. The presence of UN forces was marred by sexual scandals and lack of prospects for reconstruction. Since 2011, France has changed ambassadors to Bangui five times. Russia, which contributed forces to the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) started to see those factors as offering a rare opportunity. In a 2016 Sputnik interview with CAR’s President Faustin Touadera, there came the first signs of willingness to renew bilateral relations, barely existent after the fall of the USSR.[21]

Touadera then travelled to Sochi in October 2017 where an undisclosed comprehensive agreement was concluded with Lavrov. It reportedly included granting Russian companies’ access to the country’s natural resources. In Sochi, the CAR president requested Russia to provide weapons to the units that were being trained under the supervision of the EU mission (EUTM RCA). This paved the way for the UNSC’s December 2017 decision to authorise Russia to deliver light weapons. This unique exemption from the arms embargo, cautiously accepted by the EU and the United States, was followed by the arrival of Russian military trainers, and guards for Touadera and key government facilities. In April they intervened to stop fighting close to the presidential palace. Russian national Valery Zakharov became Touadera’s special security advisor. Symbolically, Russian forces turned remnants of the Berengo palace, home of the tomb of the former Emperor Jean-Bédel Bokassa, a grotesque CAR dictator toppled in 1979, into their local base.

Firms controlled by Prigozhin started to re-establish a diamond mine near Berengo and a gold mine in Ndassima. In August 2018, three prominent Russian journalists, Orkhan Dzhemal, Alexander Rastorguyev and Kirill Radchenko, working for anti-Kremlin media, were killed in an ambush while attempting to document Russia’s increasing role in the country’s mining and security sectors. While there is no evidence supporting a political motivation for the incident, extensive media coverage pushed the UN to seek verification of Russia’s actual goals in the CAR.[22]

Russia also engages in peace and charity initiatives in the country. In August, shortly before the Khartoum talks, Zakharov hosted a first post-war inter-faith conference in Bangui. The meeting included top Christian and Muslim clerics. Rev. Nicolas Guérékoyamé-Gbangou, the head of the CAR Evangelical Alliance, expressed his will to meet Putin to ask for help in appeasing religious tensions in the country.[23] Zakharov himself distributed aid to troubled neighbourhoods of the country’s capital. Russia also opened a clinic in Bria, a town controlled by the rebels.

Such scale of engagement couldn’t have come without opposition on the ground. With Russians having increasingly much to say and being involved in the heavily competitive mining business, anti-Russian sentiments entered national politics in the CAR. When Abdoulaye Hissene, leader of the FPRC, the most capable anti-government militia, threatened to march on Bangui in May 2018, he mentioned Russia’s growing influence as his prime motivation.[24] Jean-Serge Bokassa, minister of territorial administration and son of the late emperor, left office in April, apparently in protest against the Russian presence seen as desecrating his father’s burial site.[25] A report released on July 31 by a panel of UN experts suggests the flow of Russian military supplies sparked an arms race, with factions seeking ways to rearm.[26] A possible renewal of fighting and decreased sense of security could further hamper Russian plans for the country and the region. France is likely to do as much as it can to reverse Russia’s gains, using the UN, regional diplomacy and its experience and connections in the region.

With its push for deep, multidimensional relations with the CAR, especially with its peace and reconciliation efforts, Russia is attempting to win its first African success story. It is willing to see it serving a similar role as Somalia for Turkey, as a model for engagement in Africa. If it succeeds, the example could serve as a point of reference for other countries of the continent seeking Russian patronage. However, as in other places, the level of secrecy and the controversies surrounding bilateral relations are likely to work against this goal.

Conclusions

Africa is back on Russia’s foreign policy and security agenda and rising in importance. Moscow’s renewed interest in the African continent, which resulted in a series of political and economic ventures, produced numerous engagements following similar patterns. Their application in the context of Russia’s long-running strategy of broadening its global outreach and extending its leverage takes the form of an increasingly coherent policy, although marked by a degree of experimentation. Its efficiency is yet to be seen. As an energy-rich country, it is less focused on the oil and gas industry than China or India, but expresses a growing appetite for gold, diamonds and rare minerals such as manganese, chrome and uranium. In terms of money and time invested in maintaining long-running relations with African states, Russia’s involvement is not comparable to that of the EU, the United States, former colonial powers or emerging Asian competitors. Instead, Russia prefers to find niches where traditional rivals are not eager to go and tries to be as fast as possible in detecting new opportunities for expanding its influence. Its modus operandi seems to be based on securing fast profits in risky environments. A helping hand extended to isolated governments/factions in the form of military cooperation offers a temporary advantage over other foreign powers. With the Syrian experience, Russia gained confidence that it can be an effective game-changer in complex overseas political and security settings. Africa is a logical next destination where it would seek political and economic profits. The use of semi-private military contractors serves both political and economic goals. Additionally, it offers the Russian government an option to deny its role in a given country if it becomes too uncomfortable or risky. In the context of many occasional engagements on the continent, Russian policies in the CAR seem to be the most deep-running and comprehensive. A combination of political, security, diplomatic and business dimensions quickly made the country’s leadership dependent on Russia at the expense of France. While Russia does bring some development-oriented component to its African policies, it remains focused on government-to-government relations. Apart from gains, this may produce more anti-Russian sentiments on the continent in the future. Some of the recent achievements would not produce lasting effects. Some new programs of economic cooperation are already being halted due to lack of adequate funding.[27] Russia’s methods, cementing authoritarian regimes, damages European potential to influence developments in Africa. If Russian engagement is to be sustained, the EU will have to adjust to conditions where a Russian “alternative” could effectively undermine its own policy goals.

[1] “Lavrov embarks on tour of African countries to discuss ways to boost trade,” TASS, 5 March 2018, http://tass.com.

[2] “Russia Looks to the Central African Republic to Beef Up Its Arms Sales to Africa,” World Politics Review, 10 January 2018, www.worldpoliticsreview.com.

[3] “After Decades-Long Hiatus, Russia Seeks Renewed Africa Ties,” Voice of America, 3 June 2018, www.voanews.com.

[4] “Russia, Sudan are discussing naval supply centre, not military base/ diplomat,” Sudan Tribune, 9 June 2018, www.sudantribune.com.

[5] J. Czerep, “Competition between Regional Powers on the Horn of Africa,” PISM Bulletin, no. 75 (1146), 25 May 2018.

[6] “La Russie entame une coopération militaire avec la RDC,” Radio France Internationale, 27 May 2018, www.rfi.fr.

[7] “Russia Revisits an Old Cold War Battleground,” Stratfor, 15 January 2018.

[8] “Eritrean delegation in Russia for thorough review of bilateral relations,” Africa News, 30 August 2018, www.africanews.com.

[9] “Russia-Eritrea Relations Grow with Planned Logistics Center,” Voice of America, 2 September 2018, www.voanews.com.

[10] A.M. Dyner, “The Role of Private Military Contractors in Russian Foreign Policy,” PISM Bulletin, no. 64 (1135), 4 May 2018.

[11] A.M. Dyner, “Russian Policy towards the Largest States of North Africa,” PISM Bulletin, no. 55 (995), 5 June 2017.

[12] M. Tsvetkova, “Exclusive: Russian private security firm says it had armed men in east Libya,” Reuters, 10 March 2017, www.reuters.com.

[13] “Kreml wysyła do Libii komandosów i agentów,” Belsat, 11 October 2018, http://belsat.eu/pl/news.

[14] “Posle Sirii rossiyskiye ChVK gotovy vysadit’sya v Sudane,” BBC News Russkaya sluzhba, 4 December 2017, www.bbc.com/russian.

[15] S. Vasilieva, “Thousands of Russian private contractors fighting in Syria,” Associated Press, 12 December 2017, www.apnews.com.

[16] L. Bershidsky, “Death, Diamonds and Russia’s Africa Project,” Bloomberg, 4 August 2018, www.bloomberg.com.

[17] “Sudan says resolved to support efforts for peace in CAR,” Sudan Tribune, 4 September 2018, www.sudantribune.com.

[18] “AU adopts Sudan’s initiative for peace in CAR,” Sudan Tribune, 29 September 2018, www.sudantribune.com.

[19] I. Nechepurenko, “In Africa, Mystery Murders Put Spotlight on Kremlin’s Reach,” New York Times, 7 August 2018, www.nytimes.com.

[20] N. Beau, “Centrafrique, la France muette face à Poutine,” Mondafrique, 9 May 2018, https://mondafrique.com.

[21] “Exclusive: President of Central African Republic Hopes to Boost Ties with Russia,” Sputnik News, 17 August 2016, https://sputniknews.com.

[22] “Russian Intrigue in the Heart of Africa,” Warsaw Institute, 3 August 2018, https://warsawinstitute.org.

[23] “As Sudan hosts CAR peace talks, Russia offers to get more involved,” World Watch Monitor, 31 August 2018, www.worldwatchmonitor.org.

[24] “Pourquoi Vladimir Poutine avance ses pions en Centrafrique,” 5 May 2018, L’Obs, www.nouvelobs.com.

[25] “Explainer: What’s behind Russia’s sudden interest in the CAR,” BBC Monitoring, 23 March 2018, https://monitoring.bbc.co.uk.