Changes in Iran’s Policy on Africa

Since the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005–2013), Africa has emerged as an important direction for Iranian political and economic expansion, serving to diminish its international isolation. The country obtained observer status in the African Union and gained sympathy on the continent through humanitarian efforts: Iranian Red Crescent runs clinics in 14 African states. Iran’s current international situation pushes it to reconfigure its priorities on the continent.

Strategic Interests in the Horn of Africa

Iran’s relations with African states on the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden have been strategically important. They offer the ability to control transport via the Bab el-Mandeb strait, help in fighting piracy and extending pressure on Saudi Arabia, and conduct anti-Israeli policies. Sudan was the most important partner in these regards. According to Israel, supply routes for Hamas criss-cross Sudan. In 2008, Sudan and Iran signed a military cooperation agreement, after which the Iranians modernised the Sudanese arms industry and moored warships in Port Sudan, close to Jeddah and Mecca. The Saudis opposed the agreement. In March 2014, Saudi Arabia froze banking cooperation with Sudan, limiting transfers from the 500,000 Sudanese in the Kingdom. Hoping that a change of alliance would unblock financial aid and investments in autumn 2014, Sudan closed Iranian cultural centres, accusing them of Shiite proselytism. In 2015, the country joined the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, offering troops and mercenaries to fight against the Iranian-backed Houthis. As a reward, Saudis made a $1 billion deposit to Sudan’s central bank, struggling with shortages of foreign exchange reserves.

Relations with Eritrea went through a similar evolution. Iran offered partner relations to the UN-sanctioned state, used its territory for transit of Hamas-bound supplies and the maritime base in Assab to limit the Arab Gulf states’ influence. But in 2015, the Saudis and Emiratis managed to push Iran out of Eritrea by offering to ease the impact of sanctions on the latter, as well as military supplies and investments in infrastructure. The switch of alliance was sealed with the establishment of a United Arab Emirates (UAE) military base in Eritrea.

Given its proximity to Yemen, Iran used territory in Somalia and Djibouti to supply the Houthis. But for these states, the alliance was not particularly valuable—Iranian development aid was modest and Somalia accused Iran of interfering in its domestic affairs and supporting Somali extremists. As a result of growing Saudi pressure, Sudan, Djibouti, and Somalia broke off diplomatic ties with Iran in January 2016.

To the south of the Horn, Tanzania and the Comoros were also scenes of Iranian-Saudi competition. In both countries, Iran recently lost the upper hand. Under a Tanzania-Iran agreement on naval training, in 2016 Iranian warships docked at Dar es Salaam. It signalled an increasing Iranian focus on Tanzania as a substitute after the setbacks in the Horn. Saudi Arabia then rushed to declare Tanzania a key partner for developing trade, investment, and development projects, outbidding Iran. On the Comoros, the current president, Azali Assoumani, strengthened ties with Saudi Arabia and marginalised the previously dominant pro-Iran parties.

Support for Shias in West Africa

Iran sees this part of the continent as attractive for economic and ideological expansion. It is a prospective market for Iranian cars, popular in Guinea, Nigeria, and particularly in Senegal where Iran opened the first African assembly line of its Samand brand. Despite the predominance of Sunni Islam, the characteristics of the local Sufi brotherhoods makes their members vulnerable to conversion to Shiism. Until the 1980s, this form of Islam was only present among the relatively wealthy Lebanese diaspora, influential in Ghana and Ivory Coast. Since building African Shia communities would help Iran become rooted in the region, Iran supports local missionaries. In Nigeria since the 1980s, the Iranian embassy has helped Ibrahim Zakzaky, a Khomeini-inspired cleric, by providing him translated Shia literature. Shiites now make up about 3 million out of the 100 million Nigerian Muslims. The Nigerian authorities arrested the cleric and accuse his Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN) of planning an armed insurgency, similar to that of Sunni extremists Boko Haram, and supporting Hezbollah. Iran demands the release of Zakzaky. Sentiments among Nigerian Shiites could have an impact on the result of this year’s elections, particularly in Kaduna State, where IMN is the most active. There are 17 branches of Al-Mustafa International University of Qom and some 100 affiliated schools and mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa, mainly in its western part. They are strong centres of promoting Shiism and Iranian interests. In Ghana, Mali, Senegal, and other states, it has led to conflicts with local communities and analogical Saudi centres and contributed to increased radicalism in the region. Some development initiatives, such as the 2017 launch of construction in Mauretania of a 1000-km highway from Zouérat to Tindouf in Algeria, serve to maintain influence on the new Shia centres.

Iranian Nuclear Programme and the JCPOA

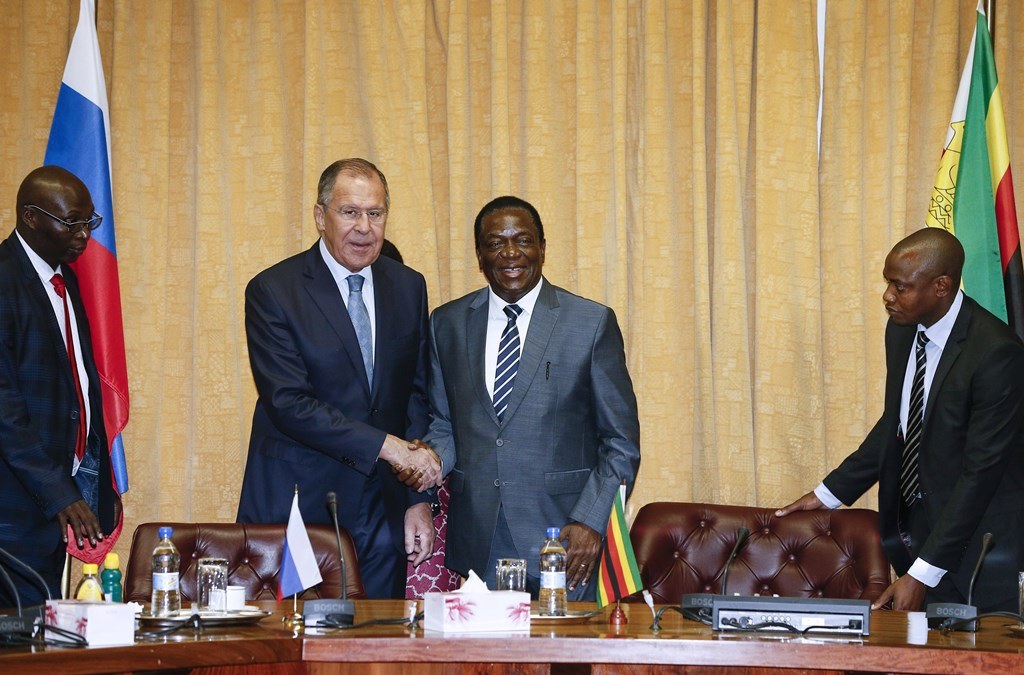

The development of Iran’s nuclear programme has given it significant motivation for building ties with African partners. In recent years, Iran has attempted to better relations with uranium-producing states, such as Zimbabwe, Malawi, Niger, and Namibia. Eritrea and Algeria declared diplomatic support for the Iranian nuclear ambitions, hoping to attract investment.

The signing of the JCPOA in 2015 inspired a number of African states to develop economic relations with Iran. From 2016, Tanzania and Kenya increased imports of Iranian petrochemical products, following only China as the biggest recipients. But since the renewal of U.S. sanctions on trade with Iran in 2018, they completely halted imports of oil products. Also, exports of tea from the East African Community, which was to grow from 2,300 tonnes in 2016 to 20,000 in 2018, have fallen. The countries now look for alternative markets for the tea. South Africa abandoned plans to import cheap Iranian oil and its telecommunications giant MTN cancelled a planned $750 million investment in fibre optics with Iranian Net.

Perspectives

For Horn of Africa states, the Saudi patronage offers more short- and mid-term financial benefits than does Iran. It makes a switch of alliance sustainable. Iran may attempt to come back to the region, which is somewhat possible in Somalia—in conflict with the UAE—and in Sudan, which in December 2018 recognised Iranian-Russian gains in Syria. But rebuilding influence to the pre-Yemen war level is unrealistic. For Iran, West Africa has emerged as the most prospective part of the continent. Shiite proselytism will develop without regard to the future of the war on the Arab Peninsula, the JCPOA, or sanctions, and transfers from West African Lebanese and converts will help to sustain Iranian ventures in Iraq and Syria. Despite the decrease in pro-Iranian governments in Africa, normalisation of relations would be in the interest of the key states of Kenya and South Africa.

Keeping transit through the Bab el-Mandeb strait free and safe is in the interest of Poland and the EU. In this context, the Saudi push for political domination of the states on this route is disadvantageous. It may lead to conditioning the use of docks at local ports by cargo ships in case of emergency only with Saudi consent.