Russia on the Global Regulation of Cyberspace

In the international debate on the status of cyberspace, Russia, like China, promotes an alternative to the U.S. and the EU vision of regulation of the internet. Russia emphasizes the importance of the state in managing the network within its borders and controlling the flow of information. But unlike China, Russia has no technical or economic opportunity to expand in the field of IT. That’s why it uses instead its diplomatic activity in the UN to undermine the principle of the open internet. Russia would gladly transfer the management functions of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), an institution registered in California and responsible for granting internet domains, to the UN level. At the same time, Russian activities on the internet go far beyond public diplomacy. NATO StratCom from February to April 2018 carried out research that showed that up to 93% of Russian-language accounts on social media were fictitious—bots, hybrids, or anonymous accounts. Of the remaining 7% that published on social media, they were private accounts or represented institutions (e.g., consulates). The internet is another medium for spreading Russian propaganda and disinformation.

Russian Projects at the UN

Russia introduced information-security issues to the General Assembly (GA) first in 1998. Until now, the Russian proposals, reported every year, did not raise controversy among UN members, as they indicated the need to inform the Secretary-General about states’ progress and positions in the field of cybersecurity. However, resolutions adopted on 5 and 17 December by the GA fit in line with the Russian vision of the role of the internet. The first concerns ‘Developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security’. Russia expanded the content of the resolution and supplemented it with a proposal for so-called “cybercode”, which is a catalogue of rules of state conduct on the internet. It increases the powers of states in managing cyberspace. The document emphasizes, among other things, that accusations that a state has organised or carried out wrongful acts on the internet should be substantiated. In case of information and communications technology (ICT) incidents, states should consider all relevant information, including the larger context of the event, the challenges of attribution in the ICT environment and the nature and extent of the consequences. States should not knowingly allow their territory to be used for internationally wrongful acts that use ICT. In addition, the Russian proposal proposed an extension of the Government Expert Group for Information and Telecommunications Development (Group of Governmental Experts, or GGE), which prepares rules of conduct of countries in cyberspace for all interested UN countries.

The second Russian resolution is about prevention cybercrime. It calls for increasing the role of the UN in coordinating cooperation between member states and a report on cybercrime prepared by the Secretary-General. Russia argues that the document is only of a technical nature and is intended to help combat illegal activity on the internet.

Reactions to the Russian Proposals

The greatest controversy among Western countries was aroused by the idea of expanding the GGE. So far, the group in the years 2004-2013 was comprised of experts from 15 countries, but in 2014-2015, it expanded to 20, and after 2016, to 25, always including Russian specialists. The GGE has met five times so far, but at the last meeting in June 2017, they failed to adopt the final report. Russia (along with China, Belarus and Malaysia) rejected the GGE’s position on the adequate application of the right to self-defence (Art. 51 of the UN Charter) for attacks in cyberspace. At the same time, the Russians proposed expanding the group, counting on deference from, among others, the countries of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, BRICS, and the Collective Security Treaty Organisation. In response to the Russian resolution, the U.S. submitted a competing document for a vote that calls for the continuation of works in the GGE’s current shape.

Western delegations (U.S., EU, Japan, Australia) emphasized that the reason for the appearance of the second Russian resolution is the desire to transfer negotiations on cybercrime from the Council of Europe to the UN level. In this way, Russia, with the support of African and Asian countries (headed by China) wants to undermine existing mechanisms to combat cybercrime.

Sovereignty on the Internet

Russia promotes the principle of “information sovereignty” on the internet. It did not ratify the Convention on the fight against cybercrime of the Council of Europe of 2001 (signed by 55 countries, and additionally by the U.S., Japan, Australia and Israel), disagreeing over the possibility of conducting operations by the services of other countries in its territory. Russia was mainly against Art. 32b of the Convention, which refers to accessing or receiving through a computer system on its territory, stored computer data located on another party’s (state’s) territory. Since then, it has been striving to create more preferential international legal regulations, including at the UN. The first proposal of the Convention on information security was filed in 2011 (then, along with the SCO in 2015, and by itself in 2017). However, Western countries have considered the Russian proposals as possibly violating rights to freedom of speech and the flow of information.

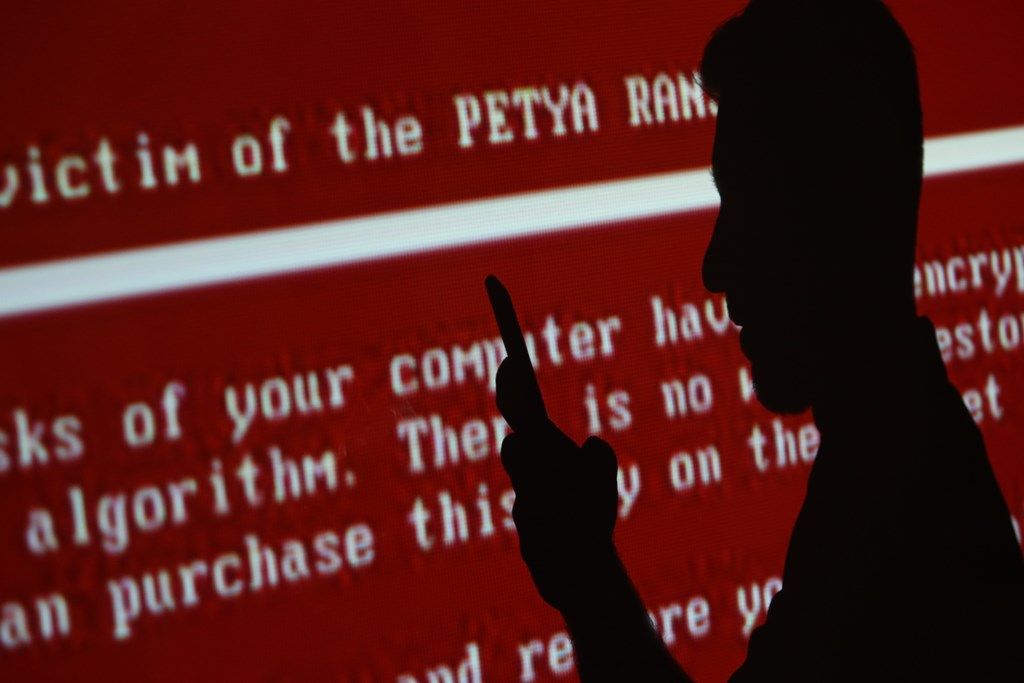

Russia sees the digital space as a place of global rivalry. According to the doctrine of information security of the Russian Federation of 5 December 2016, the global network may be used as an “information weapon” to achieve military and political objectives, to conduct hostile actions and acts of aggression. That is why Russia focuses on limiting the penetration of external content into the Russian information space. From 2016, regulations limiting freedom on the Russian network came into force, according to which companies providing communication services (such as Viber, Whatsapp, Skype, Facebook Messenger, Telegram) are to provide the Russian security service FSB with the source code of their applications and allow access to information about users and the collection of their data. In April, the Russian Federal Service for the Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor) blocked 18 million addresses to terminate Telegram’s services in Russia, whose owner refused to provide the code.

Conclusions

The Russian authorities want to create preferential international regimes for cyberspace and international information security. They promote the principle of state sovereignty over the digital space. At the same time, Russia would like to reduce the technological dominance of the U.S. in the field of IT. Due to its limited ability to compete in this area, Russia uses the broad representation of African and Asian countries within the UN to try to regulate the global IT network at the international level.

Russia wants the internet to be treated as a global telecommunications network (such as a telephone network) regulated at the international level. Proposals for the expanded group of GGE experts would allow the inclusion of countries that will defer to the Russian vision of internet development. Although the resolutions are political declarations, the work of expert groups can lead to international legal regulations, which is what the Russian authorities care about. The composition of the GGE will be the subject of further discussions because of the U.S.’s competing proposal, so it is worth Poland becoming involved in the work on the future shape of this group.

The previous Russian proposals regarding information security were supported by Poland, as they drew attention to the need for international cooperation in this sphere. However, Russia in the new resolutions, under the pretext of increasing security related to the network, aims to increase the role of the state on the internet. Therefore, due to the possibility of using such solutions for censorship and restricting the free flow of information on the network by non-democratic regimes, the proposals should be approached with caution.