France and China: Post-Pandemic Relations

A new discussion about the darker side of cooperation with China has arisen in France during the pandemic. It stems from China’s policy of misinformation concerning the spread of the virus in the early stage, which may have delayed Europe’s reaction. The shortage of medical equipment in France also has brought attention to the country’s high level of dependence on imports from China. However, France doesn’t want to strain its relations with China as that could weaken its position towards the U.S., other G7 states, and Russia. China knows it and doesn’t hesitate to increase pressure on its weaker partner.

Importance of Partnership

Trade between France and China reached €73 billion in 2019, or 7% of total French foreign trade. China is second after Germany in French imports and seventh in exports. In March 2019, during Xi Jinping’s state visit to Paris, 15 contracts worth €40 billion in total were signed between Chinese and French firms. The Chinese committed to purchasing 300 Airbus planes. France will also develop a new offshore wind farm in China. They are also interested in French plutonium transmutation. The significance of these contracts has grown with the pandemic as many French companies’ balance sheets have been ravaged.

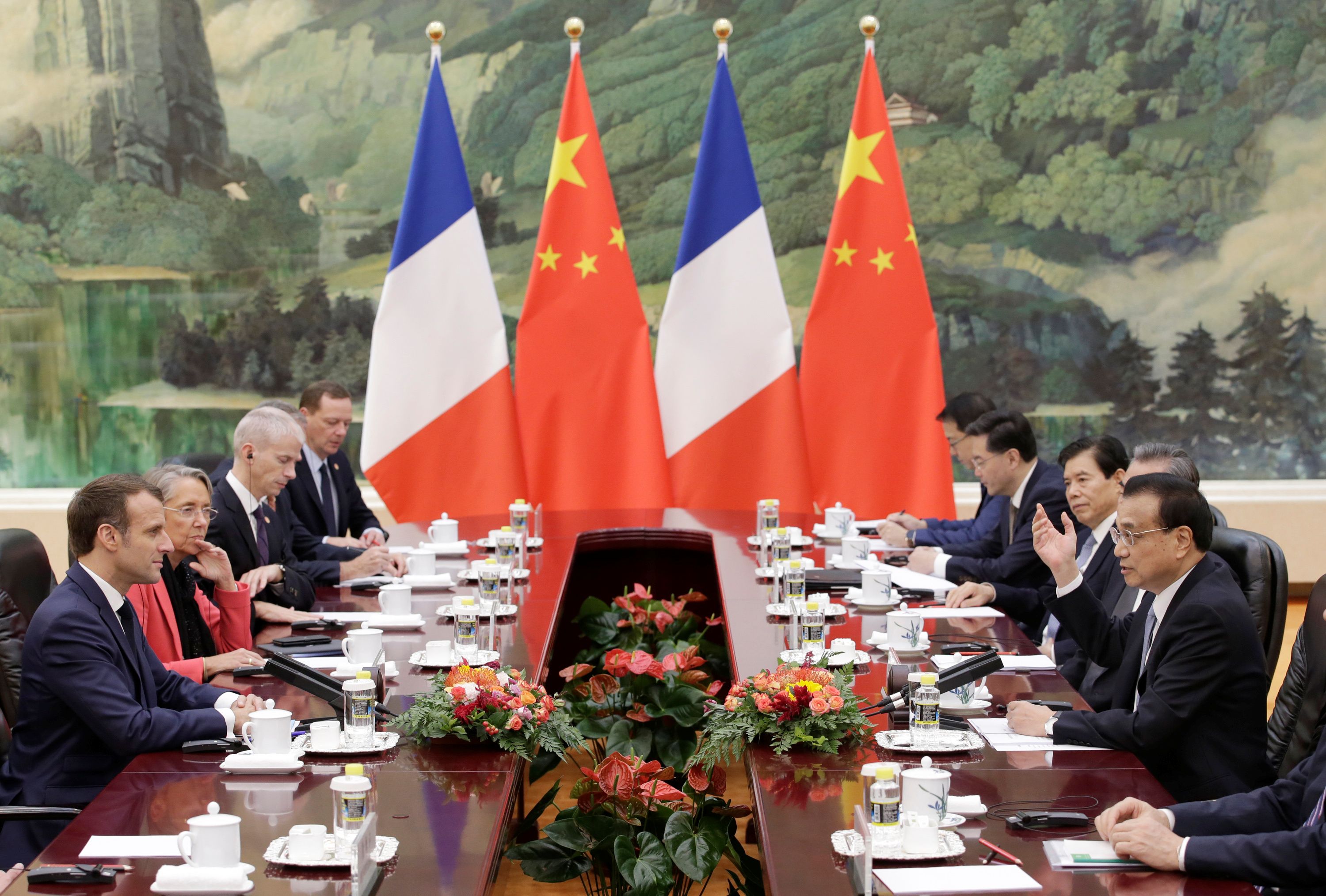

The cooperation with China is also part of President Emmanuel Macron’s foreign policy strategy aimed at reviving France’s ancient role as a “power balancer”. Macron wants to avoid the re-creation of a new bipolar system (this time, U.S.-China) by reinforcing international organisations and multilateral diplomacy. Franco-Chinese cooperation could enhance multilateral actions in such domains as maintaining the JCPOA and non-proliferation. In these fields, France can count on support of the main EU states and the UK.

The partnership with China is also important in promoting global climate efforts and maintaining the Paris Agreement. China can be useful in encouraging developing states to deliver on their climate commitments. China accounts for 27% of global CO2 emissions, but its allowable limit will decrease steadily until 2050. India and African states will then be the most polluting areas. China, as well as France, have political influence on the latter. Of equal importance is China’s engagement for biodiversity, even more so given the animal origins of SARS-Cov-2 (the new prohibitions on “wet markets” and the fight against exotic animal smuggling from Africa).

Challenges

Despite these advantages, the partnership with China is problematic on many levels. France has a persistent trade deficit with this country (€32 billion in 2019). The dependence of French industry on Chinese joint ventures and strategic goods deliveries is also troublesome. Voices in support of relocating some of French production back to the country are being raised even more frequently. The significance of this problem has been increased as China uses the sale of protective face masks as an instrument of pressure. The French government aims to encourage French companies to loosen their contacts with their Chinese joint-venture partners and move production back to France to reinforce the country’s strategic autonomy. The automobile and pharma industries are the first to be addressed by these measures. Relocation could also decrease the trade deficit. Public aid for big companies may depend on transferring production back to France. However, foreign subsidiaries of French companies are very strictly linked to the local markets. Their portability depends also on lower production costs abroad.

Transferring French technologies to China is also a matter of concern. A new P4 class virology laboratory constructed in cooperation with France in Wuhan has generated much controversy since the start of the pandemic. In 2017, the Chinese, despite binding contracts, banned the French from any control of the laboratories. French virologists warned that their Chinese colleagues did not always respect phytosanitary security rules. The Wuhan lab may also serve military objectives. Another controversy is linked to French training of Chinese doctors to conduct human organ transplants, given media reports about illegal organ trade led by China’s authorities. Nevertheless, the deep links between French science and Chinese industry justify doubt about a quick end to these kinds of cooperation.

Chinese industrial espionage in France has also raised fears. Chinese hackers have attacked the French telecommunications, aircraft, and space sectors. One task for the newly created French cybersecurity force is to halt phishing attempts. A few years ago, Macron, then the economy and finance minister, initiated the Cerbère programme to counter Chinese tech firm Huawei’s influence on the French administration and economy (halting corruption, industrial surveillance, and takeovers of French startups). After becoming president, he has insisted a few times on wider cooperation between EU intelligence services in this area (e.g., by creating a common intelligence academy).

France wants to maintain its own policy towards Taiwan and Hong Kong. The French defence group DCI is going to deliver to Taiwan a new missile interceptor system for six Lafayette-class frigates sold in the early 1990s. The move has provoked indignation and diplomatic démarche from the Chinese Foreign Ministry, without changing the French decision on the matter. When it comes to Hong Kong, France—not willing to open unnecessary fronts—seems to be much more prudent in supporting U.S. and UK initiatives. The French government has reportedly assured the Chinese authorities that it will not intervene regarding their attempts to violate the city’s autonomy.

China’s policy towards international organisations is also full of ambiguity for France. The latter would like to use the engagement of the former (especially in the WTO, World Intellectual Property Organisation, and International Labour Organisation) to neutralise China’s protectionist tendences, foster respect for human rights, more proactively go after copyright and patent-right infringers and industrial forgers. France fears at the same time that China will use its influence over developing states to dominate these organisations. The nebulous relations of Chinese authorities with the WHO presidency at the beginning of the pandemic are a good example of that. France wants to promote as an EU initiative its own plan for WHO reform, increasing the organisation’s independence from member states and making non-respect of WHO statutory law subject to sanctions.

Conclusions and Prospects

France wants to avoid breaking relations with any of its partners on global policy, including China. It recognises, however, China’s growing expansiveness and considers it a signal of the increasing tensions in Sino-American relations. Maintaining balance between the U.S. and China will become even more difficult for France. It will try to use China’s engagement in multilateral actions to make it keener to cooperation and capable of self-restraint (in matters like African debt, ecology, protectionism, and copyright infringement).

The French government also highlights the significance of solidarity in EU external policy to ensure partner-like relations with China. A more efficient decision-making process in Common Defence and Security Policy (CSDP) that abolishes the condition of unanimity could decrease Chinese influence on EU policies, achieved by its pressure on vulnerable, usually smaller Member States. French arguments on this matter would be more credible if France itself were keener to consult its actions with EU partners, for example, regarding Hong Kong. When it comes to economic relations, France supports a new EU-China investment agreement but demands China limit public aid for the country’s champions. Nevertheless, France remains silent on such crucial issues as the participation of Huawei in building the French 5G network. The state-owned Orange cooperates with European Nokia and Ericsson, but private-owned Bouygues and SFR use Chinese technologies. France declares respect for the EU’s 5G Guidelines, but doesn’t want to ban Huawei from cooperation with French companies.

Reaching more independence from Chinese joint-venture partners requires strict cooperation with other EU countries and shouldn’t be a pretext for France to deliver with its particular interests. A European approach to this challenge, for example, by supporting the European Commission proposal for the Strategic Investment Mechanism, could raise new prospects for cooperation with French industry, and also for Poland. Plans for post-pandemic revitalisation of the EU’s economy, recently proclaimed by German and French leaders, and by the EC, could also be a good opportunity. The integration of key branches of European industry could also decrease the rivalry among Member States for access to the Chinese market.