Bulgarian-Russian Relations: Between Sentiment and Pragmatism

Russia plays on the sympathetic sentiments of the Orthodox societies of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro where the memory remains of Russian help in their fight for independence. The sense of cultural closeness with Russia, often reinforced by media, favours uncritically pro-Russia attitudes and hostile views of the EU and NATO. The significance of this factor in Russia’s foreign policy is seen in the participation of 250 volunteers from Serbia in the invasion on Donbas in 2014, the coup attempt in Montenegro in 2016 before its accession to NATO, and protests in 2018 in Greece against the agreement with what is now North Macedonia.

Incidents, but Still Good Relations

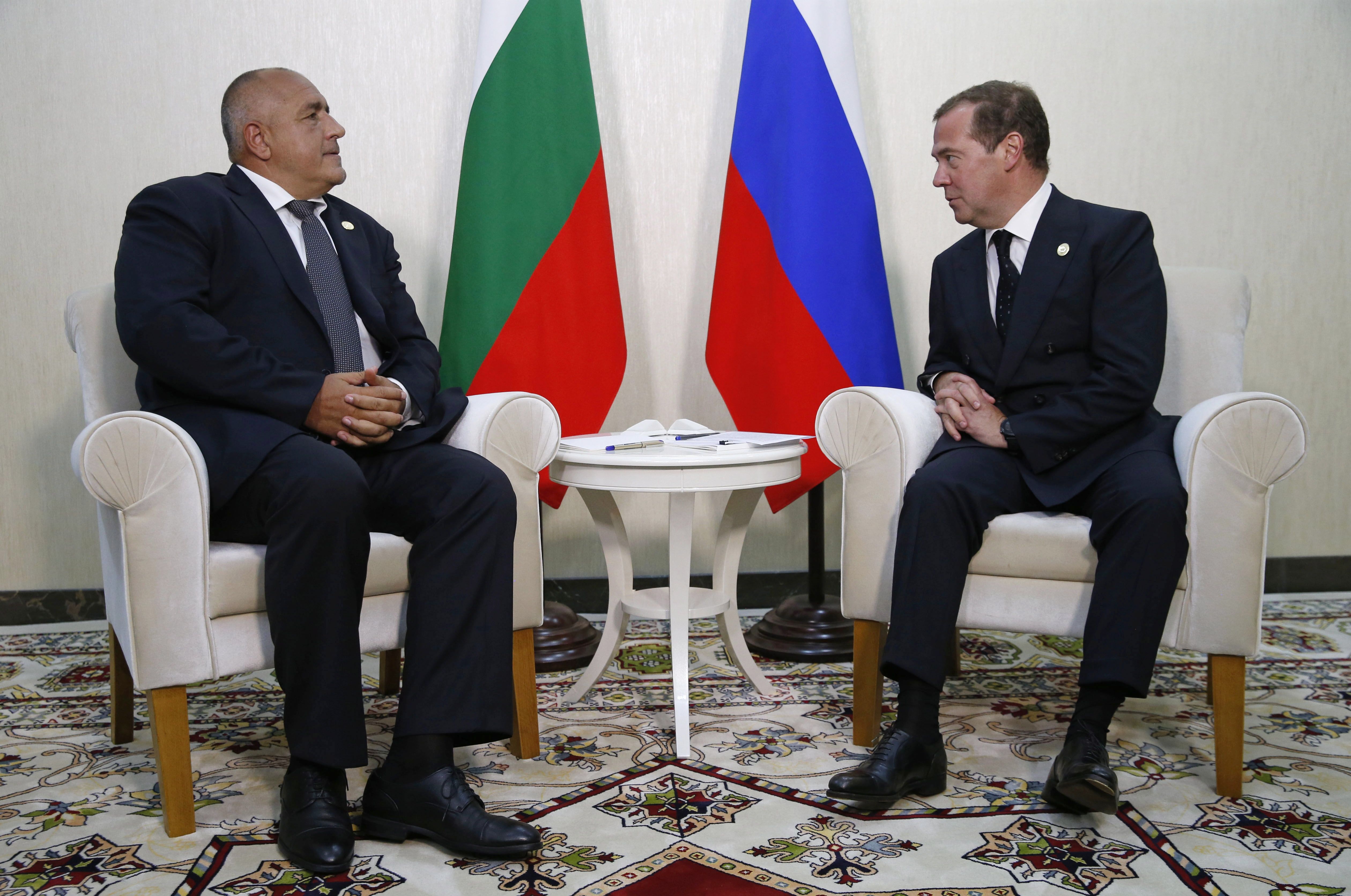

Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borisov (Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria, GERB) at the beginning of September 2019 intensified actions meant to counter the Russian secret services and propaganda. First, the Bulgarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs protested an exhibition by the Russian embassy— opened on the anniversary of the communist coup of 9 September 1944 and naming the entry of the Red Army into Bulgaria as a “liberation”. The same day, Nikolai Malinov, the leader of the Bulgarian “Russophile” movement was arrested on charges of espionage for Russia. In October, Bulgaria refused accreditation for a Russian defence attaché and expelled another diplomat. This happened shortly before local elections in which GERB, aiming to win in Sofia, appealed to the anti-Russia electorate, which is much more numerous in the capital. These actions may have helped Borisov—known for his anti-Russia attitudes though now criticized by the U.S. as being too supportive—to strengthen his position before his visit to the White House in November. The Russian reaction, though, may also prove these actions to be more demonstrative in nature. In November, Russia awarded Malinov with the order of “Friendship” and the Bulgarian government did not react to this. Further, it took until December for Russia to expel a Bulgarian diplomat as retaliation. The tensions faded after a meeting between Borisov and the Russian ambassador to Bulgaria on 6 December, after which the PM issued a conciliatory statement.

GERB, which presents itself as the guarantor of Bulgaria’s Euro-Atlantic orientation must also strive to retain the pro-Russia electorate. Even the war in Ukraine has not changed Bulgarians’ attitudes. This was confirmed by an Alpha Research survey from 2015 that found that 61% of respondents viewed Russia positively with only 30% did not. Next, in a Gallup poll from 2018, asked about the nerve-agent attack on Sergei and Julia Skripal in the UK, found that 54% of Bulgarian residents considered the matter to be an anti-Russia provocation and only 30% viewed it as a Russian assassination operation. Countering the government’s hesitation, President Rumen Radev demands closer relations with Russia. The nationalist party Attack and the IMRO-Bulgarian National Movement from the co-governing United Patriots alliance are clearly pro-Russia, as are the opposition Bulgarian Socialist Party and the Volya party. Only the National Front for the Salvation of Bulgaria from United Patriots is anti-Russia. Radev and the pro-Russia parties demand the EU abolish the sanctions on Russia. Although Borisov considers the measures ineffective and harmful to the EU’s economy, he has declared he will not undermine the unanimity of the Union on the matter. However, he has also indicated that Greece and Hungary, for example, are dissatisfied with the sanctions. This is probably meant to signal that Bulgaria would support a potential coalition of opponents to extending the sanctions.

Bulgarian Assessment of the Russian threat

Bulgaria does not consider Russia to pose a real military threat to the country. It sees it rather as a counterweight to Turkey despite traditionally good Turkish-Russian relations. Bulgaria has concerns about the large Turkish minority in the country and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s contesting borders. These fears prompted Bulgaria in October 2019 to allow Russian military aircraft to use its airspace to fly to exercises in Serbia while fellow EU member Romania would not allow Russian military transports on the Danube through its territory. In addition, before his visit to the U.S., Borisov announced that he would not agree to a NATO naval base in Bulgaria. This confirmed the 2016 decision to block a Romanian initiative to establish a permanent Alliance naval force in the Black Sea. Bulgaria considers such ideas as provocations against Russia and also sees it as affecting tourism from Russia, which amounts to about a halfmillion visitors every year, or about 7% of tourist traffic to Bulgaria.

The Bulgarian authorities also see no threats in cooperation with Russian armament companies. For example, in 2018, they contracted the renovation of 15 MiG-29 fighters for $49 million, provided that the Russian Aircraft Corporation “MiG” carries it out in Bulgaria. In 2019, they ordered special repairs to two Mi-17 and four Mi-24 helicopters from a Bulgarian company for $21 million but 67% of that order will go to Russian contractors. Because of this, the U.S. has accused Bulgaria of circumventing sanctions on Russia. The Borisov government’s decision in July 2019 to buy eight F-16s was its answer to these allegations and intended to confirm Bulgaria’s credibility with the Alliance.

Reactivation of Energy Projects

Bulgaria is susceptible to being cut off from gas supplies from Russia, which supplies about 90% of the gas consumed in the country and pays for transit to other users. Russia’s plans to exclude transit via Ukraine from 2030 after the opening of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, as well as the TurkStream (TS) branch from Turkey to Serbia and Hungary, have raised fears in Bulgaria, which is trying to get a branch of this pipeline built on its territory. Russia has suggested it will consider an alternative route through Greece, pointing out that it had spent $800 million cooperating with Bulgaria on the South Stream gas pipeline before it was abandoned. Russia probably used this argument to win favourable political and financial conditions for investments, because, in September 2019, a Saudi company began building TS on Bulgarian territory. This company will cover about 80% of the €1.1 billion cost, recovering it from the transit fees, estimated at around €180 million annually.

Russia is also the main partner to Bulgaria’s nuclear energy sector. The Russian firm Rosatom supplies the Kozloduy Nuclear Power Plant with fuel and has renovated its two reactors. Therefore, it is the most likely potential investor in the Belene Nuclear Power Plant, the construction of which was suspended by the Borisov cabinet in 2012 because of rapidly rising costs. Rosatom as the contractor received €620 million in 2016 in compensation for delivering one reactor and part of the second one. President Radev and the opposition have demanded Belene be finished. To stymie the opposition, GERB initiated a bill to authorise the government to find an investor and 13 companies expressed initial interest. The cabinet announced the investment would be fully commercial, but it has signalled that it expects to use the Russian reactors already delivered, which would favour Rosatom for technological reasons.

Conclusions

The pro-Russia sentiments among Bulgarian society and political class means a change of attitude is unlikely. The recent espionage scandals are treated as mere incidents and were used instrumentally in the local elections to accumulate political capital for Borisov before his meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump.

Bulgaria does not consider Russia a military threat and is thus cautious about strengthening NATO’s Southeastern Flank. However, the significance of Bulgaria’s stance is limited for Poland because its main Black Sea partner in security matters is Romania. What is more, while Bulgaria may be sceptical of the sanctions on Russia, so far it seems it will not seek to remove them. Therefore, to strive for EU cohesion in this matter, Poland does not need to focus on the Bulgarian opinion but rather on the biggest states, around which a possible coalition of sanctions opponents could arise.

The Bulgarian authorities see Russia as a guarantor of energy security and provider of a steady income from gas transit. Therefore, to get Russia to construct a TS branch through Bulgaria, the authorities have agreed to conditions that could minimise profits from transit. The Borisov cabinet plans to complete the Belene power plant on a fully commercial basis, which favours Rosatom because, unlike Western companies, the Russian firm is willing to take a financial loss to meet Kremlin political goals. The construction of the TS branch and completion of Belene will deepen Bulgaria’s energy dependence on Russia, which already controls a refinery in Burgas, the largest enterprise in the country, accounting for 9% of Bulgarian GDP.

The intensification of energy cooperation with Bulgaria will also strengthen Russia’s influence in the Balkans. The construction of the TS branch may undermine the profitability of EU-supported pipelines—BRUA (Bulgaria-RomaniaHungary-Austria) and TAP (Trans-Adriatic, Greece-Italy). It is in Poland’s interests to support these projects and scrutinise the TS branch similar to the review of Nord Stream 2, to see if it complies with the EU acquis.