Towards a Natural Equilibrium in Transatlantic Relations

INTERVIEW

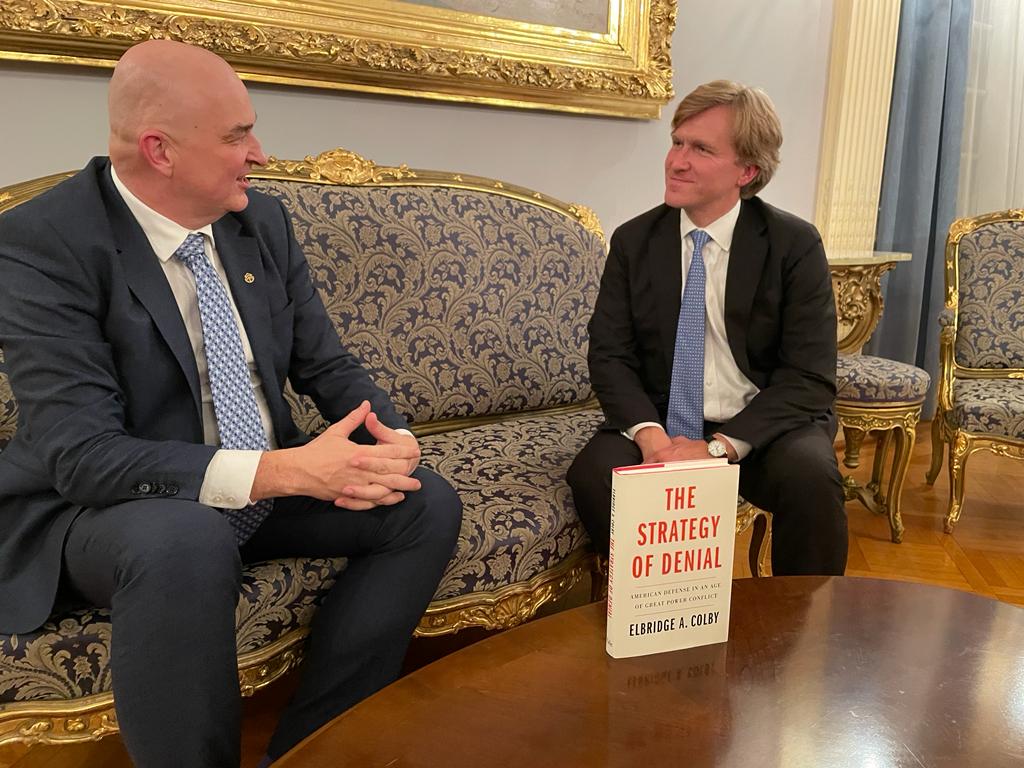

SŁAWOMIR DĘBSKI - ELBRIDGE A. COLBY

SD: I wanted to start with your thoughts on the global balance of power after Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. How much has it changed since then?

EC: Well, I think Russia has clearly weakened itself. The stout Ukrainian defence has contributed to this. Sanctions imposed by the West will diminish Russia’s economic prospects over time. I’m not really sure if it’s been net positive from the economic perspective for Europe, though, and it’s probably made the Russians more dependent on and under the aegis of the Chinese. I continue to think that the main actors in the global balance are the United States and China; then you have sort of the rising tertiary powers, like India, of course Japan is still there, the European Union as a whole. So, I don’t think the situation has radically changed the global balance, but the primary effect has been to diminish Russia’s strength.

Don’t you think though, that this war – maybe not directly – compromised certain economic models of development, particularly in Europe, when trade powers resort to relations with autocracies in order to build a competitive scheme in Europe and globally. This model was visible, tangible for all Europeans and in the United States, but dependency on autocratic powers isn’t good for security and development models.

If we step back in a sense, there was a mentality after the collapse of the Soviet Union that free market systems could afford to engage with autocratic or less free systems for a number of reasons. One was the argument that you saw in the U.S.-China context, but also in the Germany-Russia context, which was that trade would lead to liberalization. But, additionally you had the argument, particularly stronger here in the U.S. in the context of the China relationship, which was that even if they didn’t liberalize, our systems would still outcompete them. And I think, both with what’s going on in China, but also the Russia dynamic, that this hasn’t been borne out. Clearly Russia and China haven’t liberalized because of the extensive commercial interaction. I also think that it’s not been borne out that the West would necessarily outcompete particularly China, because you’ve had mass deindustrialization in the U.S. while the Chinese have continued to grow, although they’re having trouble right now. So basically where I think we’re going is at some level, geopolitics is going to be upstream of economics – you have to have efficient markets and a competitive commercial system, of course. It’s not all politically determined – to the contrary. But, the notion that we would go back, as some are saying, including some leaders in Europe, to this notion of a Thomas Friedman-style borderless world idea is just delusional. Any company that thinks that is going to be the case is not being very smart.

There are those who say, and they claim that they belong to the church of realists, that it’s a good thing that Russia made mistakes and somehow preemptively acted Ukraine as an ally of China. It undermines its position, as you said, and it’s good for the free world and the U.S. if taking into consideration this grand competition ahead of us with China. What are your thoughts?

First of all, I think it’s important to say and I know you’ll agree that what’s happening in Ukraine is obviously a massive human tragedy. Getting to your question, the Russians have failed so badly and been weakened for at least some amount of time. Now, I’m of the view that the positives and negatives of this are not all in one direction. The Russians have been weakened, their attempt to use military force to seize neighboring territory is hopefully failing, the Euro-Atlantic community is standing together in support of Ukraine – these are all good things. On the other hand, there are a couple of things that are less reassuring. One is that the Russians, I think, are going to become – at least under Putin’s leadership, and quite possibly under future leadership – more dependent on the Chinese. So if China’s our primary rival and Russia’s now more under its control – that’s a problem. Ten to fifteen years ago, if the Chinese had wanted to do something and they called up Vladimir Putin, he would’ve said ‘I’m going to do whatever I want’. Five years ago he might have said ‘I’ll take it under consideration’. Now he’s really going to be beholden to them because that’s where Russia’s exports are going to go and where their political support is coming from; Moscow has no real alternative. That’s not good. I also think that European economies and societies have taken major hits as a result of decoupling from Russia and support for the Ukrainians. That’s a problem too. Chancellor Scholtz’s visit to Beijing suggests that that means they’re going to be limited in how hard they’re going to be with the Americans vis-a-vis China. That’s reality, but from our point of view here in the U.S., that’s sort of a mixed result. There’s a view of our alliances, especially observable from elements of the Biden Administration, that they’re the three musketeers – one for all and all for one. We’re all in it together on every issue. But I don’t think that’s how it works because I’m a realist. I think we should expect countries to work with us where their interests are aligned and where they have the capabilities to do something. I don’t want to sound too gloomy – clearly it’s better that the Russian are failing, or seem to be I hope, but I don’t think it’s decisive.

Alright. There’s kind of a descriptive part to the story when we say that Russia undermined itself and that it could be good for the free world. How should we use this opportunity, if it really is one, of Russia weakening itself? How can we strategically explore this mistake?

I don’t have a strong view on what exactly the political or geopolitical goal within Europe vis-à-vis Russia should be. My own view is that we have an interest in the Russians not being completely under the thumb of the Chinese and having some space for autonomous action. Now that poses a tension with our interests in a free, sovereign, and secure Europe in the sense that those two goals can push against each other. You can see our perspective on the behavior of India as an example of managing this tension. That said, our goal should be a secure Europe with a clear line that the Russians must respect and that Europe is strong enough, but with the overriding goal that the U.S. genuinely prioritize Asia and China.

Europe is strong and secure with or without Ukraine. What do you think about that?

Well, I’m not in favor of bringing Ukraine into NATO because I think that, from my perspective, we already have an alliance that covers most of the European continent and is far larger in power terms and resources than Russia. Thus even a pretty expansive vision of our interests are well-secured by NATO as it is. And the risks and costs of including Ukraine in NATO are, of course, real. This is by no means to wash our hands of Ukraine, though. Ukraine has a strong military and has shown a great deal of resolve and we should continue supporting them. But my view is that the Europeans should take the lead in supporting Ukraine (and in their own defense) so the U.S. can prioritize Asia while continuing to support Europe in a more focused way. This to me is the natural equilibrium.

Yes, but even if Ukraine is strong and proves itself militarily capable, what they wouldn’t have without NATO is nuclear deterrence. How do you see the prospects of American nuclear deterrence over Europe and possibly granting it to Ukraine without membership in NATO?

Ukraine is in a very difficult geographic position fundamentally and in terms of how the Russians regard it. American nuclear deterrence becomes directly relevant with respect to countries that are within our defence perimeter. So any large conflict that the Americans fight with a major power rival like Russia or China is invariably going to have a nuclear dimension because you can’t fight a large war with one of them without nuclear weapons being relevant. In a sense, all wars among nuclear-armed states are nuclear wars – they are at least shadowed by the potential for nuclear use. In light of this, one of the areas where the American contribution to NATO should remain strong is in nuclear deterrence and that should unambiguously cover European NATO as a whole. In the case of Ukraine, they’re not in the U.S. defence perimeter, so U.S. nuclear weapons are not directly relevant. Obviously, nuclear deterrence casts a shadow; this is kind of ambiguous and not always easy to define. That’s part of the deal, though. But I don’t think that’s just consigning Ukraine to failure. There are no fixed rules for nuclear weapons, but it’s difficult to use them to conduct wars of conquest. Generally speaking, an aggressor is best off using a strong conventional force and then you can using nuclear weapons as kind of a shield or a coercive extra level of effort. And I think the Russians are actually demonstrating that they agree with that theory, which is why they’ve been using their conventional forces without employing their nuclear weapons. And the good news is that, by defeating Russia’s conventional forces, Ukraine is really undermining Moscow’s theory of victory, despite Russia’s great advantages in nuclear forces.

There’s another theoretical aspect that a losing power can benefit from using nuclear weapons. There’s no historic precedent of this, though. If you’re winning, you can double down your effort, forcing your opponent to capitulate. No good can come of it if you’re losing – you can only lose more.

Right. That’s the thing about nuclear weapons. There’s a tendency to simplify the effect of nuclear deterrence and say that it comes out of a magic box. Actually, if you even think about historical examples – I remember famously Herman Kahn, who was one of the more hawkish nuclear strategists of the classic era, saying that if the French had had nuclear weapons, or maybe Poland, in 1939 or 1940, they might have deterred the Nazis. On the other hand, if an aggressor is pursuing partial but still real gains and the costs to the defender of using nuclear weapons, even defensively, is total destruction by retaliation from the aggressor, then the defender might not even use it then. Now Poland, of course, the Germans completely occupied, so maybe in that case you would pull the temple down over your head. But, I think what that tells us is that nuclear weapons are extremely important but that there are no fixed rules, especially when you factor in the international and political ramifications. Clearly the country that first crosses the nuclear threshold since 1945 is going to take an enormous step. And if you’re doing that in ways that are manifestly offensive and aggressive, it’s going to be very, very damaging. And I think that’s one of the reasons Putin hasn’t used them.

Kurt Campbell [Deputy Assistant to the U.S. President and Coordinator for the Indo-Pacific] confirmed at the Aspen Security Forum that Russia’s war against Ukraine already influenced the conversation between Washington and Beijing, including in the nuclear dimension. Do you see any convergences in the approach to nuclear weapons between China and the U.S. because of Ukraine and Russia’s public threat?

Well, dangerous conversions in the sense that the Chinese are undertaking a massive nuclear buildup. I’m far less sanguine about the situation with China than some people are. I think the Chinese, and I think what Campbell said was, that the Chinese are going for a tactical, short term pause or sort of turning down the volume in the Sino-U.S. relationship. I don’t see a fundamental change in Beijing’s approach. They’re embarking on a massive nuclear buildup, so they’re supposed to now have fifteen hundred warheads by the middle of next decade. If there’s a convergence, it’s that the Chinese are actually trying to become closer to our [U.S.] own nuclear forces. That’s very disturbing. But – and to the point we were discussing earlier – I think what they’re probably trying to do is become conventionally dominant in the Asian theater and then rely on their growing nuclear forces to deter the U.S. from credible first use on behalf of its allies.

OK. This leads me to other questions, though. In your view, how important is Russia for China? Would the Chinese allow Russia or Putin to be defeated?

So, I think the Chinese seem to regard the Russians as very important. It’s almost by a process of elimination. If you look at the great powers or centers in the world, obviously Beijing regards the Americans as their primary rival. Japan and India are increasingly aligned with the U.S. because they’re directly threatened by China. And Europe is kind of fractious, but probably increasingly seen as aligned with the U.S. At this point you’ve worked through the major powers and Russia is all that’s left. They share authoritarian perspectives, they even have a personal relationship. But I think more fundamentally that China doesn’t want to be isolated. It’s basic Metternich or Bismarck. Xi Jinping was in Saudi Arabia this week, which shows me that they’re reaching out to try to find additional significant partners – also ASEAN, probably some of the African or Latin American countries. My expectation is that the Chinese will stick with the Russians. It’s been interesting that they have not vocally and very directly supported the Russians militarily. At the end of the day I think it’s a relationship of interests. My impression is that Xi Jinping probably thought that Putin was going to succeed and do well and now he’s screwing up. That’s not something China’s going to pay for. But the relationship looks like it’s going to remain and indeed deepen, with China as very much the senior partner.

I think that was kind of the presumption behind this Russia-China announcement in February last year just on the eve of Russia’s attack. In my view, Xi is quite unhappy with the Russian performance in Ukraine. Do you think that’s accurate?

That certainly strikes me as right. Putin has become more of a liability and he’s probably causing a lot of embarrassment and difficulties for the Chinese. There may be advantages for China in the sense that now Russia can export may things to China at this point. But on the whole that is a negative for China.

There’s also the view that there’s a strategic link between Ukraine and Taiwan. Do you agree with that? For me, the trouble is about defining this link. Of course, intellectually we can create out of these two examples one territorial model that is dependent on others in terms of defence. How far can this kind of strategic analogy be developed?

There’s some relevance, but I’d say that it tends to be exaggerated. Taiwan, while not a formal American ally, is effectively within the U.S. defence perimeter. Ukraine is not. China is far, far stronger in general, but also relative to Taiwan than Russia is to Ukraine. The main issue I have is that it’s often said that the Ukrainians need to defeat Russia in order for China to be deterred from attacking Taiwan. I don’t think that’s true. There’s something to that point, but that’s not the primary factor. I think that what China’s leadership is going to look at is, above all, can they take Taiwan successfully. That’s the biggest thing and primarily derived from a practical assessment of the military balance. And then perhaps political factors relating to Taiwan, the U.S. for instance, does China believe that Taiwan’s never going to fall in its lap, that it’s going to be deep green [increasingly pro-independence], etc. Those are the bigger factors. If Beijing actually thought that in order to win over Taiwan Russia needed to win Ukraine, it would be supporting Russia a lot more. Because if they thought that that’s where Taiwan’s fate was actually going to be determined, they’d care a lot more about how Russia was doing militarily in Ukraine. But they’re not behaving like that.

So your argument is that for theorists, strategists, Putin tying these two together intellectually may be attractive. But for the Chinese it doesn’t work. I think the Russians may be more inclined to argue, particularly towards the Chinese, that we’re actually in the same boat.

Yes. A very good point. Actually, the Russians probably make that exact argument. Blinken said something like this recently and on Twitter I joked, saying that we have to win South Vietnam to deter the Soviets in Europe. That obviously wasn’t true. If you want to strengthen the position in Europe vis-à-vis the Soviets, then strengthen the position in Europe vis-à-vis the Soviets.

In terms of models, the way the U.S. is engaged in defending peace in Europe and the Pacific are different. In Europe you have this trip wire concept with nuclear deterrence coming in front of the wire. But, in Taiwan… So here’s my question. Do you consider deploying American troops to Taiwan just to deter China? If there’s a model that we wish to use to make deterrence credible on both fronts, then why not copying the European one in the Pacific?

Well, there’s a very serious concern, which is the deployment of U.S. forces on Taiwan is generally to be understood as one of China’s three red lines. The other being Taiwanese independence and Taiwanese nuclear weapons. What I would say is that the U.S. should be prepared to do everything necessary to be able to mount an effective defence of the island at a reasonable cost.

Do you think that was the reason why they tried to deter Pelosi’s trip?

The way I think about the Pelosi trip is the best foreign policy for America is to speak softly and carry a big stick. Right now, we’re kind of doing the reverse – speak loudly and carry a small stick. We have people going to Taiwan all the time, people are talking about Taiwan all the time. That’s good to a certain point, but we’ve passed it. Now we seriously risk pressurizing the situation, creating a lot of attention and focus by China. But we’re not strengthening our position as much as we’re talking about it and I don’t think that’s wise.

So deployment would be a solution?

It would be a very, very serious step. I’m not advocating it at this point, but I think everything should be on the table that is directly connected to ensuring an effective defence of Taiwan. I’m not talking about recognizing an independent Taiwan or Taiwanese nuclear weapons, but I have in mind things that effectively contribute to defending what is after all the status quo. I’m saying, as we have for many decades, that we are opposed to the resolution of Taiwan’s fate by coercion.

In your writings, you claim and make the point that in order to be successful on the Chinese front, the U.S. needs Europe on its side. How can that be done?

We need Europe on our side to some extent. My view is basically that what matters at the end of the day in geopolitics most of all is the hard power balance and that’s primarily military, but also economic because economics is what produces military power in the modern world and just general national strength. If you get the military balance right, everything else is basically manageable. But, if you don’t have the military balance right and you’re not defencible, then all the other international institutions and soft power won’t make a difference. I think that Ukraine is really an illustration of this. If the Russians had rolled through Ukraine or at least the eastern part of the country and captured Kyiv, I don’t think our sanctions or G7 statements or NATO statements would make a difference. What’s made the difference is the fighting prowess of the Ukrainians and the fact that they’ve been supplied with advanced weaponry at scale – and the incompetence of the Russians, it seems. The lesson for what we need is a favorable military balance in the Pacific. I have a less demanding view of the Europeans in terms of their active involvement in the military balance in the Pacific or economic warfare campaign than some. What’s critical to my eye is that Europe take care of its own security and Poland is really a leader in that, and I applaud it because that is what I think all of our allies should be doing – going above four percent towards five percent, really taking responsibility for your own defence. My view then is that Poland is really pulling its weight. It’s obvious that its primary threat to Europe when viewed through this military lens is Russia. China’s a very distant threat, although that could change over time – but for now it is Russia. So what I would expect from Poland, speaking as an American, would be a basic alignment on the China issue, I mean don’t undercut us or try to equivocate. But I’d put less pressure on Europe on China if they pull their weight militarily. So I tend to be a little bit less supportive of the very assertive and forward-leaning positions on China from some of the Baltic States or Central and Eastern European countries, for instance with delegations visiting Taiwan. Because I reject the implicit idea behind some of these moves there that by doing something on Taiwan, they’ll get the Americans to pay them back in Europe with direct military presence over the long haul. I don’t think that’s the right deal. The better deal is to take care of yourself and your security as much as possible with some, but more limited American help. Let the U.S. worry mostly about the Pacific.

Thanks so much for your nice words on Poland…

Well its true…

But there is another extreme if we picture Poland as a leader in taking care of security in Europe. There are other countries neighboring Poland – namely Germany. What can we do with Germany and how can we mobilize them to do the right thing?

That’s a great question and it’s been something I’ve been thinking a great deal about over the last few years. The Zeitenwende announcement was very encouraging, but now there are real questions about whether there’s going to be any follow through. The Germans are still at a very low level of defense spending. Look, we need to dispense with the idea that they’re naive or that they don’t understand the role of power. This is a very sophisticated country, it’s the largest economy in Europe. We need to make sure their incentives are properly arranged such that they really feel the need to build up their military in a way that promotes European security within the European structure, NATO structure, etc. The Biden administration’s made a big mistake by being so positive towards Germany that there’s no pressure really. There’s this idea that they’ll do the right thing and I don’t really see that happening yet. What we need to do is hold up countries that are doing the right thing, like Poland and others – Romania’s increasing their defence spending, and many are, although not to the level of Poland – and also put real pressure and say look, this is really obligatory and there are going to be consequences in the political relationship if that doesn’t happen. We need to do it in a way that’s constructive and rational, but that’s clear. I try to do that when I talk to the Germans, which I do a lot. It’s important to be candid with them – and with Poland too – and say this is the reality, this is the problem we have to deal with together and at the end of the day, if you’re not going to move on this, there will be consequences.

Bridge, thank you very much.

Thank you.