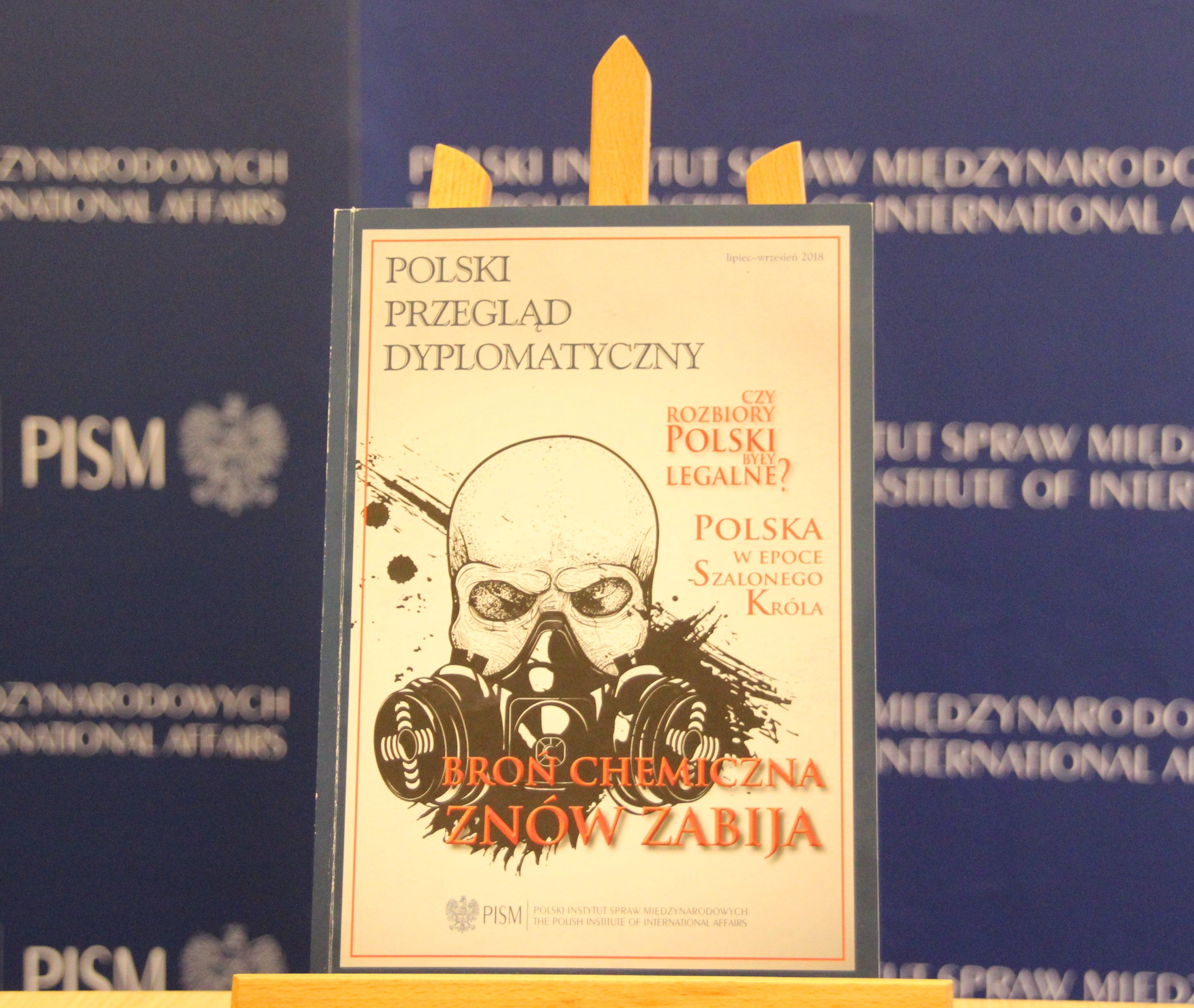

Poland in the Age of the Mad King by Sławomir Dębski

PISM

PISM

The hundredth anniversary of the end of World War I is being commemorated in an atmosphere of decadence of the liberal world order – an order created by the United States and maintained by it until the present day. Its main achievements are: democratisation of politics between nations; recognition of nations’ rights to self-determination; universalisation of international law together with the prohibition of unilateral use of force or a threat to use it as a foreign policy tool, as well as a cooperative approach to common security and trade liberalisation. These systemic achievements are reflected in institutionalisation of international relations.

One hundred years ago, president Woodrow Wilson initiated the shaping of the new order, making US military intervention in Europe and its help with saving European democratic powers dependent on replacing Pax Europea – an international system based on the concert of powers – with a totally different system and, at that time, a revolutionary one, which was to be based on the concept of the “concert for peace.” The first attempt failed. Americans led to the creation of the League of Nations, but they did not join it, withdrawing from their involvement in the security of Europe. And so war came to Europe again. It was in the name of maintaining peace that they decided to stay in the Old Continent after World War II. They led to creation of the UN, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, they initiated global trade liberalisation (GATT), they helped rebuild Europe, initiating the Marshall Plan, they established the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, which provided free Western Europe with conditions for economic and political integration. The liberal vision of international order, supported by the United States, emerged victorious from the Cold War, so the order was further extended – former Soviet satellite countries regained their sovereignty and became members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union. The international system established by Americans was named Pax Americana.[1]

Wilson firmly believed that any authoritarianism should be regarded as democracies’ common enemy, since democracies do not fight with each other, and if they do participate in wars, they do it to extend the democratic systems. On 2 April 1917, while justifying the request to declare war against Germany by the United States, in his address to a Joint Session of Congress, Wilson appealed for the war not to be against the German nation. The United States was declaring war on autocracies and the idea of the concert of powers. Following victory, Wilson wanted to replace it with ”a concert for peace:“, as he referred to his idea: „ “We have no quarrel with the German people. We have no feeling towards them but one of sympathy and friendship, but [...] a steadfast concert for peace can never be maintained except by a partnership of democratic nations. No autocratic government could be trusted to keep faith within it or observe its covenants. It must be a league of honour, a partnership of opinion. [...] Only free peoples can hold their purpose and their honour steady to a common end and prefer the interests of mankind to any narrow interest of their own.”[2]

On numerous occasions, Wilson’s ideas would be derided in literature on international relations. Henry Kissinger, for example, devoted considerable part of his academic activity to tackle his concept, what can be explained, among other things, by the fact that he himself was fascinated by Prince Clemens von Metternich, co-author of the “concert of powers” paradigm. He wrote a doctorate on it and would always perceive international relations through the prism of this notion.[3]

Nevertheless, Wilson’s liberal vision became an important school of thinking (competing with the thought of the realist school, which places reflection on “power” above international law and its institutions) in American strategic thought of the last century and still remains a point of reference in the debate on liberalism or idealism - if you want - and the place this policy approach occupies in the world politics. Even though Wilson himself (like the term “liberalism,” and “idealism” both still misunderstood) is not held in high esteem by the White House today.

The latter is no good news for Poland – a state that should be classified as one of the principal beneficiaries of the liberal world order. It is not without reason that references to Wilson and his role in the rebirth of Poland’s statehood are constantly present in public speeches by Polish decision-makers.[4] Rightly so, since if the United States had not supported the principle of self-determination of peoples, and if Wilson’s concept of international relations democratisation in the name of maintaining peace had not prevailed, it would have been difficult to imagine international environment so favorable to Poland’s rebirth a hundred years ago.

Unfortunately, there are many indications that the strategic forecast for Poland is much worse today, which poses a significant challenge for Poland and creates a necessity to take active steps in restoring favorable for Poland and its region international environment , or at least countering negative tendencies in global politics. It is worthwhile to have a closer look at them.

***

In the US National Security Strategy announced in 2017 – first such document drafted by the Trump administration – the current international order is presented as an environment of continuous rivalry. The United States – still the most powerful state in the world – is, therefore, to use its advantage to maximise its own benefits. One of the key tasks ahead of the American politics is, in turn, regaining its economic competitiveness. In the background, there is a hidden conclusion that in the current world order - promotion of which was a permanent element of the US politics in the last century - America lost its competitive advantage. Therefore, the Trump administration set itself a task of improving this situation by changing the existing rules. Of course, one question arises here: will the system still be effective despite a change of the rules governing it? The Trump administration is convinced of that. Experts worldwide, however, are losing faith in it rapidly. The United States’ priority is to regain economic advantage, using all available measures – including through “balancing” the relations with its allies. The Trump administration believes, for example, that because the American national security “umbrella” is expensive, the allies should pay more for its maintenance, and allied relations cannot justify the lack of trade balance in their relations with the United States.

Kori Schake, current Deputy-Director General of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), in her article published by “The New York Times” after the June G7 summit in Canada and the American-North Korean summit in Singapore, emphasises that the United States’ self-limiting in its own strength was of significant importance to the functioning of the liberal international order. It, of course, dominated all its allies, but in order to maintain the coherence of the system, it would not always politically discount this asymmetry, and would very often limit itself to enhance the coherence of the alliances and the entire international system, where it fulfilled a hegemonic role.

As an expert close to the Republican Party she reminds: “America benefited from supporting its allies. The American security “umbrella” enabled friendly governments to attract investment and grow peacefully. [...] The system allowed America and other countries to share the costs of preserving common defence and the free movement of goods and people (although sometimes others put in less than Americans would like). The world has never seen anything like this — a superpower constraining itself to such a degree — or the peace and stability it brings. Of course, America did not always get it right; often it was clumsy, failed to live up to its ideology, and broke its own rules. [...] But the results speak for themselves. It has been over 70 years since the last great-power conflict. [...] The global economy has grown about sevenfold since 1960, adjusted for inflation. [...] Contrary to the president’s core complaint, the American-led order isn’t that expensive, especially as compared with the alternatives. About 40 percent of America’s gross domestic product was allocated to the military during World War II. It now stands at less than 4 percent — not an unreasonable price for a tried-and-true insurance policy.” According to Schake, this approach, deeply rooted in the American strategic thought, is now being replaced with another way of thinking which slowly begins to transform into the “Trump doctrine” of strategic importance. “The administration’s alternative [to the liberal world order] vision for the international order is a bare-knuckled assertion of unilateral power that some call «America First». More colourfully, a White House official characterised it [...] as the «We’re America, Bitch» doctrine. This aggressive disregard for the interests of like-minded countries, indifference to democracy and human rights and cultivation of dictators is the new world Mr. Trump is creating. He and his closest advisers would pull down the liberal order, with America at its helm, that remains the best guarantor of world peace humanity has ever known. Weare entering a new, terrifying era.”[11]

On 6 June 2018, Wess Mitchell, Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs in the State Department, made a speech in the Heritage Foundation, Washington, in which he tried to present the main assumptions of the US European policy, including relations with its allies: “The world that our grandparents and parents built is a place where we enjoy a degree of freedom and prosperity that would have been unimaginable to past generations. Together with our allies, the United States ushered in one of the longest periods without Great Power war in recorded history. [...] The President’s focus is on rebuilding our defences by shoring up our depleted armed forces and recapitalizing our nuclear deterrent; on rebuilding our economy by making American businesses more competitive, stimulating investment, restoring manufacturing, and fighting to give American companies a fair playing field in international markets. [...] Today Europe is indisputably a place of serious geopolitical competition. The starting point of the Europe strategy is to say: We have to take this reality seriously. That means taking geopolitical competition seriously. America has to take it seriously. And Europe has to take it seriously.”[5] Defending the West has been the common objective.

Mitchell presented his vision of continuation of American involvement in the liberal international order – even though he skilfully avoided using this term, replacing it with the “West,” which he defined by referring to the common values set out in the preamble to the Washington Treaty, 1949, establishing the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. This rhetorical ploy also allowed for his smooth transition to Trump’s political message, delivered in his Warsaw speech in July 2017. Mitchell emphasised that the aim of the Trump administration is to save the “West” – the “extraordinary community of nations,” and, according to Mitchell, NATO constitutes its significant institutional manifestation.

While answering questions after his speech Mitchell would, however, avoid comments on Donald Trump’s recent decisions about imposing tariffs on EU steel and aluminum, withdrawing from the Iran nuclear deal – in spite of the protest by European signatories to this agreement – and also threats to impose tariffs on products of German automotive industry. He simply stated that he was not responsible for economic affairs. Meanwhile, several days later, an open dispute broke out between President Trump and other G7 leaders, followed by Trump’s refusal to sign the joint statement after the summit.

This situation justifies questions about the coherence of messages sent by the US Department of State, not so much with the administration’s programming documents, but rather with President Trump’s actions and statements. It is hard to resist the impression that there has been a communication chaos. Stephen Walt – an American professor of international affairs at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, a key proponent of realist theories of international relations – while commenting on Trump’s implementation of foreign policy, defined him as “mad king.”[6] The President of the United States indeed seems to believe that the system of international relations, alliance commitments, strategic, political and economic interdependencies constitutes a corset which hamstrings him, depriving him – confident of his own superior negotiating skills – of the ability to fully spread his wings and get for the United States far better conditions for being a key member of this system and any organisation constituting its institutional manifestation. Trump seems to be discouraged from arguments referring to strategic and long-term interests; perhaps due to his own situation in domestic politics – contestation of his political mandate, his capacity to lead and the policies initiated by him – he is determined to make a quick “return on his investment.” Hence his predilection for acting against American strategic tradition and political conventions, and disrespect for multilateral institutions as well as principles of international law. As a result, however, the confidence in US policies and the credibility of American leadership, as well as – which is of considerable importance to Europe and, especially, Poland – American security guarantees have been on the decrease. Therefore, calling this situation the age of the Mad King does not seem to be an exaggeration.

Of course this is no good news for Poland, either. The tradition of strategic thought indicates that the international situation, favourable to Poles, has always been the result of the liberal approach to international politics, based on the democratic principles, right to self-determination, respect for sovereignty and non-interference in internal affairs. . The possible retreat from the liberal world order and its institutions – including the parallel integration within the most developed countries in the world, the EU and NATO member states – towards an international authoritarian regime constitutes a negative trend for Poland. But only the ultimate replacement of the “concert for peace” with the rivalry of the “concert of powers” for the spheres of influence and dominance could create a systemic threat for her.

Experts on American foreign policy are deeply concerned about the future of Pax Americana. Until now, there have been concerns that a threat to this system would come from the outside, that the United States would weaken as a result of excessive involvement in extending the order created by it, or that it would fall as a result of a dramatic rise of power of any candidate aspiring to become a global hegemon, such as China. Today, it is the possible US abdication from the role of the “first citizen” in the liberal world order that is a cause for concern. Additionally, this concern is expressed not only by followers of the opposition Democratic Party.

Robert Kagan in his last essay: Trump’s America does not care published by “The Washington Post” reminded that Pax Americana was established on the assumption of asymmetrical relationships between the United States and its allies. Yes! – America's allies could spend less money on common defence. Yes! – they could develop faster, and even gain an economic advantage over the United States. Instead, they did not participate in the arms race, they did not aim at having nuclear weapons (in most cases) and their own spheres of influence, so they also gave up on strategic rivalry with each other. The responsibility for global security rested with America. “At the core of the world order was a grand bargain,” writes Kagan. “To ensure the global peace that Americans sought after being pulled into two world wars, the United States became the main security provider in Asia and East Asia. In Europe, the US security guarantee made European integration possible and provided political, economic and psychological safeguards against a return to the continent’s destructive past. In East Asia, the American guarantee ended the cycle of conflict that had embroiled Japan and China and their neighbours in almost constant warfare since the late 19th century.” As Kagan emphasises, it was not only about security: “The security bargain had an economic dimension. The allies could spend less on defence and more on strengthening their economies and social welfare systems. This, too, was in line with American goals. The United States wanted allied economies to be strong, to counter extremism on both the left and right, and to prevent the arms races and geopolitical competitions that had led to past wars. The United States would not insist on winning every economic contest or every trade deal. Other powers — like Japan, Germany and other nations — did at various times believe that they had a reasonably fair chance to succeed economically and sometimes even to surpass the United States. That was part of the glue that held the order together. […] Trump is not merely neglecting the liberal world order, he is milking it for narrow gain, rapidly destroying the trust and sense of common purpose that have held it together and prevented international chaos for seven decades.”[7]

One may, of course, deem Kagan’s conclusion too far-reaching. The analysis of the programming documents adopted by the Trump administration, which define the strategic direction of American politics, does not authorise such unambiguous and dramatic conclusions; the same shall apply to public communications by the US State and Defence Departments. But it is the statements made by President Trump himself that cause rift between the assumptions developed and announced by the administration and their application in political practice. It may sometimes give rise to doubts as to whether the President is actually familiar with the documents programming his policy that he has signed and whether he associates with them. Kagan, however, is not the only person with such doubts – they are shared by a growing number of observers of Trump’s policies politics. The United States used to stabilise the international order, sending a clear political message about the direction of the evolution of international politics supported by it. The world could anticipate Washington’s stance even before the possible political intervention; countries interested in good relations with the United States would make adjustments to their own stances and policies without any American suggestions, persuasion or pressure. That is what the soft power described by Joseph Nye was all about.[8] Today, the ability to anticipate the direction of American policies worldwide diminishes. In the long run, this means trouble for the United States, and even greater perturbation for the countries that benefit from the American hegemony.

Richard Haass the President of the Council for Foreign Relations in March 2018 wrote an epitaph on the liberal world order: Liberal World Order, R.I.P.[9] Many participants of the debate on the international order realise that defining it as “liberal constitutes a certain degree of simplification. This was well put by Haass, who rephrased the words by Voltaire who, in turn, said that the Holy Roman Empire was neither holy nor Roman nor an empire. Thus the “«liberal world order» is neither liberal nor global nor orderly.”[10] The concept of liberal world order indeed tends to be misleading. Perhaps also to the American President. This term is often used in the conviction that it constitutes a derivative of political doctrine of Liberalism. This is too big a simplification. Such connection indeed exists, but at a very basic level – just like political liberalism assumed limiting the omnipotence of executive power by laws guaranteeing individual freedom (which developed later towards human rights), and by representative bodies as well as independent judiciary, in international relations autocratic order based on the concert of powers, spheres of influence and primacy of force over law constitutes an exact opposite of the liberal international order based on respect for sovereignty (freedom) of states, the principle of self-determination of nations, international law and multilateral institutions. And if this autocratic order does create any legal system, it is connected with bilateral agreements between powerhouses which take precedence over the law aspiring to become universal.

***

Poland is an undeniable beneficiary of Pax Americana and US guarantees for Europe’s security. The liberal approach, in turn, is one of the strongest in the tradition of Polish foreign policy. In the last phase of World War I, Polish political elites correctly recognised that Poland’s national interest is connected with the democratisation of international relations. Admittedly, the liberal international order was imposed owing to the dominance of the US global powerhouse, but this order is as much American as it is Polish in the sense that Polish political thought made its own original, intellectual contribution to its definition, independent from the American one.

In 1797, in a secret additional protocol attached to the then signed convention on the final liquidation of the Polish State Russia, Prussia and Austria declared that the name “the Kingdom of Poland” was to be deleted from their political dictionaries once and for all, and simply cease to exist.”[12] The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, signed nearly 150 years ago was, therefore, nothing new in the experience of Poland and the entire Central Europe. It is in this context that the anti-imperial tradition of Polish way of thinking about international affairs was shaped throughout recent centuries. Its roots, however, are much older. The origins should be traced back to the concepts formulated as early as in the 15th and 16th centuries, throughout wars and disputes between Poland and Lithuania and the Teutonic Order, bringing about the need to stop its expansion in both the military and political field and, as a result, also in the legal one. It led Polish lawyers to their own concepts of just wars, disbelievers’ rights to self-determination and living in peace, and ultimately condemnation of crusades.[13] This historical experience would pave the way for the two features permanently present in Polish foreign policy: anti-imperialism and legalism. They would subsequently inspire the search for Polish political thought at the time ofthe greatest trial – during the partitions.

Six years after the partitioning powers had signed the secret additional protocol on banning any activities leading to the rebirth of Polish Statehood, Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, a Pole in the service of tsar Alexander I and Russian foreign minister, offered European powers a revolutionary project of the European League assuming a reform of politics between nations and adopting a new liberal European order. It was to stop the spiral of rivalry between powerhouses, resulting in endless wars that would devastate the continent. This was a short break in the period of European wars that started in 1791 and were instigated by the French revolution, and attempts to crush it on the one hand, as well as the attempts made by Napoleon Bonaparte at universalising its achievements by expanding the French empire by force, on the other one.

Another stage of this rivalry was on its way. Czartoryski proposed a political project which would not only give a chance to avoid the catastrophe, but also promote liberalisation and institutionalisation of relations in Europe. European powerhouses were to look for a way to avoid the conflict of interests, agreeing that maintaining peace shall be their common interest. The aim of this new alliance of sovereign European states was, therefore, not to keep or seek a new balance of power, but to create new rules safeguarding peace in Europe. Czartoryski proposed to limit the risk of new conflicts between European states by a “constitution” of international politics, codification of signatories’ rights and responsibilities. From then on, the international relations should be governed by the principle that war could only be declared after having exhausted all possibilities of political and diplomatic mediation. In this new system neutral states were to play a key role of intermediaries. The new liberal European order was to be propounded jointly by England and Russia, and its adoption was intended to put an end to coalitions against France and great powers’ quest for dominance over smaller nations which, under the new order, were to gain right to self-determination. In his Memoirs, originally published in French in 1865, Czartoryski wrote: “I would have wished Alexander to become a sort of arbiter of peace for the civilised world, to be the protector of the weak and the oppressed, and that his reign should inaugurate a new era of justice and right in European politics. This idea quite absorbed me, and I endeavoured to reduce it to a practical form. I drew up a scheme of policy which I sent in the form of a circular for ambassadors to all Foreign Courts. This circular, which was intended to inaugurate the new system, prescribed a line of conduct characterised by moderation, justice, loyalty, and impartial dignity.”[14] Alexander “was the only man in his Empire capable of understanding, to a certain degree, the significance of this system, and adopting it with conviction, and even as a matter of conscience. At the same time, he only entered into my ideas superficially; being satisfied with the general principles and the phrases in which they were expressed , he did not think of going deeper into them or appreciating either the duties which the system imposed upon him or the difficulties which would necessarily impede its realisation. My colleagues, who seemed to share my opinions on many points, listen with approval to the details of my system of policy, which comprised the emancipation of the Greeks and the Slavs [from the South]. So long as the only matter in question was the supremacy of Russia in Europe and the increase of her power, those who listened to me were on my side; but when I passed to the objects and obligations which should be the consequence of such supremacy, to the rights of others, and the principles of justice which should check ambition, I observed that my audience grew cold and constrained.”[15]

Czartoryski proposed the new rules of international politics having on his mind such a paradigm of thinking about politics in which it would be possible for an independent Polish state to be reborn. In the then conventional way of thinking about European politics, resurrection of Poland was considered a threat to European balance of power and must have caused political and military counteraction. “My system, through its fundamental principle of repairing all acts of injustice, naturally led to the gradual restoration of Poland. But I did not pronounce the name of my country, not wishing to encounter diplomatic resistance. This idea rested in the spirit of my work, in the tendencies of Russian politics. I spoke of the progressive emancipation of the nations which had been unjustly deprived of their political existence, and I named the Greeks and Slavs [from the South] as those whose restoration to independence would be most in conformity with the wishes and opinions of the Russians; the principle was to be held equally applicable to Poland. I felt the propriety and necessity of this, as no Russian was ever on his own initiative or his own will favourable toPoland; and I afterwards became convinced that there is no exception to this rule.”[16] Czartoryski’s project of new liberal European order required cooperation between Russia, England and France. In order to implement it, those three powerhouses had to resist the temptations to weaken each other, give up on trade wars and wars of aggression, “come forward as a judicial and moderating influence, to prevent violence, injustice and aggression.”[17] None of them was either ready for that or wanted it. Therefore, the conflict was inevitable.

After defeating Napoleon, a new European system was established by European powerhouses at the Congress of Vienna, but it had nothing to do with Czartoryski’s liberal ideas; quite the contrary, not only did it restore ancien régime, but it would also intensify and institutionalise heavy-handed methods used in international politics. Pax Europea assumed a coalition of powerhouses against liberalism and its damaging influences on both political systems in Europe and international relations. Admittedly, after the Congress of Vienna the “Kingdom of Poland” reappeared on the political map of Europe, but as a rump state, non-sovereign and in a personal union with Russia. Czartoryski did not, however, give up on his endeavours and was consistent in trying to inspire European policy makers and diplomats as well as the general public, which would become more vocal in clamouring for a say in European policy issues, with the liberal idea of an international politics reform. In his Essay on Diplomacy[18] issued in French in 1830, originally published under a pseudonym as Manuscript d'un Philhellčne, arguably so as not to arouse suspicion that there may be a current political intrigue behind it – wrote: “I am the state, as Louis XIV would say. Half a century ago all rulers in the continent would say the same. This was a universally accepted doctrine, but it is no longer so today. Today, there is no Christian ruler who would not say that peoples do not live in the world for his satisfaction and pleasure, but it is him, the ruler, who is there for the happiness of the people, and any government – with a desire to rule legitimately – has to be based on justice and aimed at the common good of the society it rules. [...] This is a major step forward made by humanity, and nobody will ever turn it back from this path. The government may have an interest in committing injustice, the nation, however – cannot, and if we do tend to admit that the national good constitutes the only goal and general rule for every government, then why should we not agree once that the good of the whole humanity should be a standard for an active external policy, that is one which goes beyond the principle of self-defence? Why the Christian civilisation, which managed to implement sound doctrines in countries’ own policies, should not also extend on their foreign affairs and mutual interests?”[19] Czartoryski would therefore persuade that there is a connection between the evolution of systems of European states, aiming at submission of the executive authority, including foreign policy conducted on behalf of the states, to parliamentary scrutiny, and the need for a reform of the international system. Institutionalisation of autocratic regimes at an international level was, therefore, in his opinion impossible to maintain in the long run. According to Czartoryski, creating a new system based on sovereign equality of states, assuming self-control of powerhouses in the name of maintaining the common good, that is peace, constituted the future.

It should be noted that Czartoryski pointed out the connection between a state's internal organisation and its activity in international politics one hundred years before President Wilson did the same thing. Autocracies oppress their own citizens, so why should they resist from violating the freedom of other peoples? Having regard to Poland’s experience of foreign interference in its internal affairs in the 18th and the 19th centuries, he emphasised that the new liberal European order has to implement the principle of respect for sovereignty and non-interference in internal affairs, otherwise it will be difficult to talk about freedom: “Every sovereign nation – like an individual in the common order – has a right to its own government and building the happiness of the nation in its sole discretion. Therefore, no other nation, not being able to rule another, and, especially, not being able to regard it as its property or a tool, has a right to interfere in all those things the nation believes to be good for the development of its prosperity. Under no pretext should a foreign intervention impose a common system to forcefully – what is against the law and nature – transform two nations into one civil society.”[20]

Nevertheless, Czartoryski’s concepts lacked political impulse and power that would support their implementation, resulting from either the weakness of supporters of the heavy-handed international order, or from the hegemonic advantage of one of them, ready to impose a liberal revolution on others or bring them around to the new system. As we know, in the early 19th century, tsar Alexander I did not choose to “come forward as a judicial and moderating influence” on international relations. It was only one century later that a politician willing to take this burden on appeared on the stage of history.

Wilson possessed what Czartoryski lacked – the power able to implement the vision of democratisation of international relations. Erosion of the old order – the concert of European powers – resulted from the devastating war. Liberal concepts of the gathering steam America, fenced off by the ocean from Europe engulfed in life-and-death rivalry, gradually began to transform into a political tool for changing the world according to Washington’s will. The weakened European powers were not able to ensure security and they needed American presence in the Old Continent to defend peace. Unfortunately, this project was not supported by US citizens. The United States withdrew from the system created by itself. War broke out in Europe once again. This lesson exerted a strong influence on American strategic reflection and conceptualisation of the post-war liberal world order. Americans returned to Europe during World War II and they are here until today. But even though they won a notable victory in the Cold War, it is difficult to call the American policy of managing post-war peace a success. The process of uniting Europe was not completed. A common, united and peacekeeping Europe did not emerge. After the enlargement of NATO and the European Union, the powers supporting the liberal project of transatlantic order deemed the process to be complete. That was a strategic mistake. In fact, Europe was again divided into a democratic part, integrating within the European Union and NATO, and one that was to be left at the mercy of the initially weak authoritarian tendencies. In Eastern Europe, political systems based on interdependence of the world of politics, secret service, business and criminal environment were shaped. The liberal order would start to coexist with the authoritarian one. As a result, the latter regained its vigour and authoritarian Russia, which in 2008 began to invade its neighbours bringing the threat of war back to Europe, was reborn. At the same time, the American capability began to be exploited in Afghanistan, where the United States, deprived of valuable allies, got strategically stuck. Shortly afterwards, it was entirely wrongly invested in the Middle East, where it became finally exhausted. This is how the USA threw away the capital of social support from their citizens in order to promote and maintain the liberal world order. In this regard, Trump is only a symptom, not the result of disappointment of the American society in the role of the United States in the liberal world order. This system is, therefore, immersed in a deep crisis, even though it is too early to pronounce its death.

***

The situation of the international order crisis in the age of the Mad King requires clarifying its fundamental issues. The return of international politics into the “concert of powers” mode constitutes an existential threat to Poland. One requirement of Polish raison d’etat is to counter authoritarian tendencies in international politics while backing those which at least support the foundation of the liberal world order. In Europe, the institutional manifestation of this system is embodied by, inter alia, the political and military presence of the United States. Hence Poland’s policy should not only aim at maintaining it, but also– when there is such an opportunity– at strengthening it. What is obvious, conducting policies aimed at pursuing this goal requires convincing the European partners that enhancing American presence in Europe is in their own interest as well and – despite fears in certain European capitals– it is directly conducive to harmonising tensions in transatlantic relations. The way the Trump administration pursues its policies is prone to disruptions, and their costs are unequally allocated across Europe. Europe should skilfully negotiate this fact in its relations with Trump’s America and take advantage of the instruments recently created by with personal Trump’s blessing and political support perhaps a temporary one, to strengthen the transatlantic ties. In a crisis of the international order one cannot be sure that the institutions and instruments of transatlantic cooperation created when the weather was nice will be equally effective in a storm. Schematic thinking will certainly not bring effective solutions, as there is a need for more pragmatic flexibility.

Both the tradition and practice of Polish foreign policy indicate that the criterion of the attitude to international law in the assessment of the concept and political decisions taken by the partners, even the strongest ones or with a vocal and efficient lobby, shall be maintained at any cost. This reason of state is expressed by announcing to all members of the international community that they cannot expect that Poland will allow activities which are unlawful and illegal under international law, even if its partners cease to respect the principles of international law. Under such circumstances, Poland will be consistent in pursuing its policy of disallowing violations of national law as an instrument of conducting politics, whether they concern Eastern Europe, the Middle East or any other part of the world. And it will never be about a policy towards any country, but about defending the principle of universality of international law, which Polish political thought about international affairs traditionally considers to be the civilisational achievement of mankind.

There are traditional foundations of Polish national interest in thinking about Poland’s foreign policy – anti-imperialism, sovereignty and legalism.21 It is also them that constitute the natural compass for both policy makers and the society, which ratifies their political choices in a democratic state. We should always remember about them and absolutely stick to them in crisis.

All states in our region share a situation similar to the one of Poland. It is typically characterised by the experience of strategic loneliness, which poses a direct threat to the security of entire Europe. Presence always constitutes an answer to loneliness. Not a declaratory one, not a prospective one, but physical and ready to act. Owing to the heritage of the “great contract” between the United States and Europe, Western European states are not able to meet the greatest strategic demand of Central Europe. They are not able to generate presence, since they have no necessary capability for that. Of course, their cooperation under the American security “umbrella” shapes the conditions necessary to harmonise development across the entire continent, but in a security deficit, this potential is of minor importance.

All Central European states will aim at minimising the effects of possible American-European tensions in the region. The Three Seas Initiative, perceived in Washington as one of very few multilateral projects that the Trump administration is in favour of, as well as the Bucharest Nine, as a symbol of European’s serious approach to Trump administration’s postulate about equal allocation of common security costs may turn out to be helpful instruments. Such policies could also be favoured by a closer cooperation between the states of the region in strengthening defence capabilities, including a coordinated policy of acquiring armament. However, one should be aware of the fact that this idea is extremely difficult to implement due to the tactics of America, as it is usually, regardless of its administration, uninterested in reducing its own negotiating power.

[1] About the history and evolution of the liberal world order: G. John Ikenberry, Liberal Leviathan. The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order, Princeton University Press, 2012

[2] W. Wilson, War Messages, 65th Cong., 1st Sess. Senate Doc. No. 5, Serial No. 7264, 1917, p. 3–8, www.ourdocuments.gov. Wilson’s intuition suggesting that democratic states are less eager to get involved in armed conflicts with other democracies was scientifically proven only at the end of the 20th century by scholars conducting studies on the theory of democratic peace. The pioneer in this research was M. Doyle, Kant, Liberal Legacies, and Foreign Affairs, “Philosophy and Public Affairs” 1983, vol. 12, issue no. 3, p. 205, 207–208.

[3] Consult his greatest literary work: H. Kissinger, Diplomacy, Simon & Schuster, 1994 (the Polish edition, 1996). See also idem, World Order: Reflections on the Character of Nations and the Course of History, Penguin Press, 2015.

[4] On the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of Wilson’s famous fourteen-point speech before the Congress on 8 January 1918, Poland’s President Andrzej Duda sent an occasional telegram to the President of the United States, Mr Donald Trump: Depesza okolicznościowa Prezydenta RP do Prezydenta USA [An occasional telegram to the President of the United States from the President of the Republic of Poland], “Prezydent.pl”, 8 January2018, www.prezydent.pl. See also: Speech by Beata Szydło, Poland’s Prime Minister: O przyszłości Unii Europejskiej na XV Forum Polskiej Polityki Zagranicznej [On the future of the European Union during the 15th Foreign Policy Forum], PISM, 9 November 2017, www.pism.pl/Konferencje/ XV_FPZ

[5] Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs A. Wess Mitchell’s speech at the Heritage Foundation (as prepared) (June 6), U.S. Embassy in Georgia, https://ge.usembassy.gov

[6] S. Walt, Twitter account post of 10.06. 2018, 16:51: “I’m beginning to suspect Trump the Mad King doesn’t like allies because meeting with them interferes with his golf schedule. Plus, all these other leaders just can’t hide the fact that they know WAY more than he does.”

[7] R. Kagan, Trump’s America does not care, “Order from Chaos” [blog], Brookings, 17 June 2018, www.brookings.edu

[8] J. Nye Jr., Soft Power. The Means to Success in World Politics, Public Affairs, 2005.

[9] R.N. Haass, Liberal World Order, R.I.P., „Project Syndicate”, 21 March 2018, www.projectsyndicate.org

[10] Ibidem.

[11] K. Schake, The Trump Doctrine Is Winning and the World Is Losing, “The New York Times”, 15 June 2018, www.nytimes.com

[12] Acte d’Accession de S. M. l’Empereur des Romains à l’article séparé et secret de la Convention du 26 (15) Janvier entre S. M. l’Emperor de toutes les Russies et S. M. Prussienne, w: F. Martens, Sobranije traktatow i konwiencyj zakluczonnych Rossijej s inostrannymi dierżawami, vol. 2, Sankt Petersburg 1875, p. 303–304.

[13] Cf.: L. Ehrlich, Paweł Włodkowic i Stanisław ze Skarbimierza, scientific editor M. Cichocki, A. Talarowski, Narodowe Centrum Kultury [National Centre for Culture], Teologia Polityczna, 2017.

[14] Memoirs of prince Adam Czartoryski and his correspondence with Alexander I, preface L. Gadon, foreword K. de Mazade, vol. 1, Kraków 1904, p. 228.

[15] Ibidem, p. 228–229.

[16] Ibidem, p. 229

[17] Ibidem, p. 230.

[18] Marceli Handelsman believed that the “Essay on Diplomacy,” from which this quotation is taken, was written in 1827. Andrzej Nowak, in turn, assumed it was written in 1823. “Jerzy Skowronek wrote that the Essay was written in phases over the years 1826–1827.” M. Kornat, Reforma dyplomacji i legitymizm narodów. Adam Jerzy Czartoryski i jego Rozważania o dyplomacji, w: A. Czartoryski, Rozważania o dyplomacji, Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2011, p. 361.

[19] A. Czartoryski, op. cit., p. 232.

[20] Ibidem, p. 187.