Rapprochement with Russia, Alienated from the EU: AfD Congress Confirms the Party's Radicalisation

The June congress of Alternative for Germany (AfD) confirmed the growth of the party’s radical wing and its anti-system, populist character. The AfD’s proclamations of anti-EU views are accompanied by demands for close cooperation with Russia. In the coming months, the AfD leadership will seek to make political gains from growing fears of inflation and the energy crisis through social appeals.

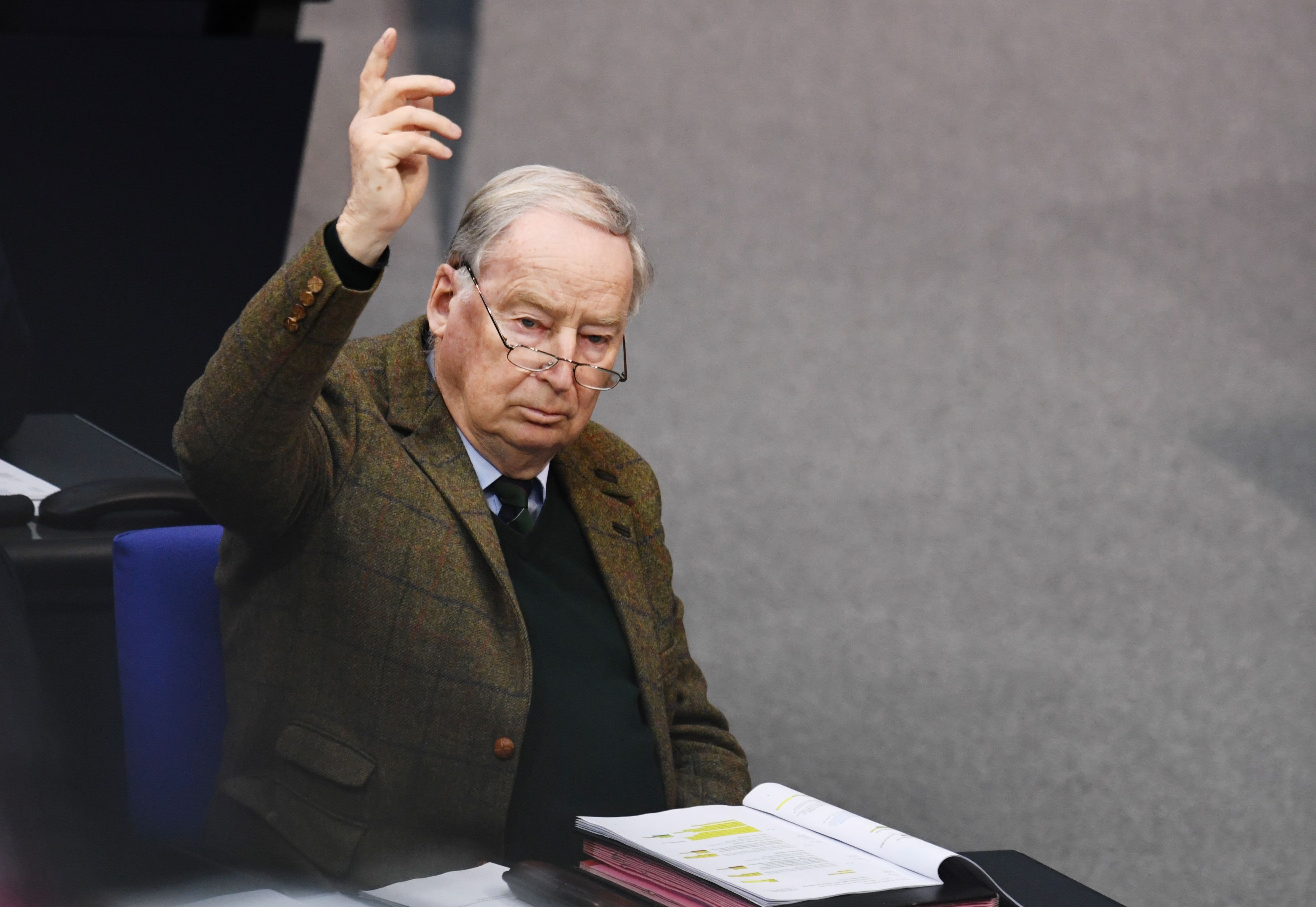

MATTHIAS RIETSCHEL/Reuters/Forum

MATTHIAS RIETSCHEL/Reuters/Forum

The AfD, founded in 2013 in response to the eurozone debt crisis, was initially a party that combined demands for the abolition of the single currency and greater care for the German economy with social conservatism. The refugee and migration-management crisis of 2015, the rise of anti-Muslim sentiment, and criticism of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s policies led people with an extreme mindset to join the AfD, linked, among others, to the “PEGIDA” movement, which has as its goal to fight against the “Islamisation of Europe”. Bottom-up pressure from them has led to a gradual evolution of the party toward the extreme right.

The AfD and Germany’s Political Scene

Before the 2021 Bundestag elections, the AfD adopted a radical electoral programme that contained demands for a “Dexit” (Germany’s exit from the European Union). This demonstrated the growing strength of members of the former nationalist “Wing” faction and its leader Björn Höcke. “Dexit” demands and criticism over sanitation restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic allowed the AfD to retain 10% of the vote in the Bundestag elections (compared to 12% in 2017). This result was perceived in the party as a disappointment, but it confirmed that the party remained a permanent element of the political scene.

AfD’s slogans promising social security, curbs on immigration, and a conservative axiological turn are mainly finding an audience in the eastern, poorer Länder. It won the Bundestag elections in Saxony and Thuringia and came in second in Brandenburg and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, indicating that its base of support is among populations in the former East Germany (GDR). The AfD is channelling the disillusionment of residents in these areas with the social and economic effects of German reunification by promising to “finish the revolution” of 1989.

This trend was confirmed by this year’s Landtag elections. While the party failed to get its representatives into the Schleswig-Holstein parliament, it landed slightly above the threshold in elections in North Rhine-Westphalia and Saarland.

The AfD has been isolated by other parties at both the local and federal levels. Since spring 2021, the entire party has officially remained under counterintelligence surveillance as a potential threat to the constitutional order. In January 2022, Jörg Meuthen, who represents the moderate sector of the party, resigned from his AfD membership and position as co-chairman in protest against the rise of extreme tendencies in the party.

The June AfD Congress

Elections for new party leadership were held in Riesa, Saxony, on 17-19 June. Tino Chrupalla was re-elected and Alice Weidel became the party’s co-chair. This result would not have been possible without the support of Höcke and his supporters. The balance of power in the AfD indicates that the co-chairs will have to consult him on major decisions. The congress, though, amended the party’s statute to have only one chair lead the party at a time. This opens the possibility that Höcke will agree to be a candidate and seek to lead the AfD in the future. The politician’s position is also strengthened by his appointment as head of the party’s committee on organisational reform.

The party congress became a battleground over its agenda. Höcke’s proposed vision of foreign policy included a call for self-dissolution of the EU and its replacement by a more loosely-knit community of European states. It also stressed the need for Germany to maintain good relations with Russia, which sparked a discussion and opposition from delegates from western Länder. The proposal was sent for further work in the party structures at the end of the congress.

The AfD and Russia’s Aggression Against Ukraine

AfD members have hardly hidden their pro-Russian sympathies in previous years, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has put the grouping in a difficult position and confirmed internal divisions within the party. The AfD leadership is trying to balance between openly supporting Russia and presenting itself as a “peace party” looking after Germany’s interests by doing everything to avoid involving the country in a conflict with Russia.

In response to Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s speech in which he announced a shift in Germany’s foreign and defence policy, AfD Co-Chair Chrupalla condemned Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, however, while also alleging the “complicity” of the West, which supposedly disregarded Russia’s security interests in Central and Eastern Europe. The AfD leader thus de facto recognised Ukraine as part of Russia’s sphere of influence.

The openly pro-Russia stance of the party leadership and the club in the Bundestag provoked opposition from some MPs who blamed Putin for the outbreak of war. Despite the internal tensions, the AfD’s overall narrative is based on emphasising the need for Germany to remain neutral. Only four of AfD’s 80 MPs in the Bundestag voted in April in favour of a joint proposal by the other coalition and major parties calling on the government to supply heavy weapons to Ukraine. Although the AfD’s programme includes demands to strengthen the Bundeswehr, most of the party’s deputies did not support the government’s creation of a special fund for military refitting, arguing that it means an “arms race” with Russia.

In the first weeks of the war in Ukraine, the parliamentary club in the Bundestag was also divided between supporters and opponents of sanctions on Russia. The AfD leadership, manoeuvring between these groups, initially formulated demands for exemptions from sanctions and boycotts of Russian cultural and sports institutions. Faced with rising inflation and visions of an energy crisis, AfD openly calls for Germany’s withdrawal from all sanctions and the launch of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline. Russian natural resources and low energy prices for households and industry would confirm the benefits of German-Russian cooperation and neutrality over the war in Ukraine.

The AfD’s stance on NATO and its support for Ukraine remains ambiguous. While the party’s programme identifies NATO membership as a pillar of Germany’s security, prioritising good relations with Russia contradicts the Alliance’s interests and the provisions of its strategy, and means in practice weakening NATO’s credibility and defence capabilities.

The AfD’s position reflects the views of the party’s electorate. According to surveys, only 12% of its supporters agree to supplying arms to Ukraine and 14% back continued support despite rising energy prices. By contrast, as much as 70% of the party’s voters favour the EU undertaking negotiations with Putin in order to improve relations with Russia.

Conclusions and Predictions

The party congress confirmed AfD’s radicalisation, increasingly visible in the last few years. Appeals to voters based on social frictions, combined with social demands, are finding receptive ground in Germany’s eastern states, while discouraging voters in the west. The party’s focus in this regard is likely to intensify. The AfD will remain present in the Bundestag, but its influence is limited mainly to the former GDR areas. The other parties will continue to keep it isolated.

The AfD will seek to discount growing fears of inflation and energy supply difficulties while declaring its will to protect German families from these phenomena by presenting itself as the party of “peace” and “common sense”, especially in the context of Germany’s dependence on Russian energy supplies. The most dangerous scenario, both from the point of view of Chancellor Scholz’s government and Poland’s interests, would be a major energy crisis in the fall and winter combined with an economic recession in Germany. This could result in a rise in support for AfD (especially in the east) and public pressure on the government for a return to energy cooperation with Russia.

The AfD’s attitude toward NATO and Russia indicates that in a period of rising tensions between the countries of the Alliance’s Eastern Flank and Russia, the party will demand the withdrawal of the Bundeswehr and the non-fulfilment of Alliance obligations, putting these countries at risk.

AfD politicians’ vision of relations with Russia, anti-EU positions, and demonstrated will to undermine the foundations of NATO contradict Poland’s interests and indicate that any dialogue with the party is highly unadvisable. Moreover, there is a risk that any possible contacts with Polish political circles, media, or NGOs could be used by the AfD to legitimise its actions, especially in the sphere of foreign policy.