Post-Brexit Paradoxes of Britain's Legal Immigration Policy

The issue of immigration policy (including the free movement of persons within the EU) has prominently featured in British debates since the beginning of the 21st century. Between 2010 and 2024, the Conservative Party promised in successive election campaigns to reduce the scale of this phenomenon, and Brexit allowed the UK to introduce a points-based system modelled on those functioning in Australia and Canada. However, under Boris Johnson’s government, the criteria for coming to the UK were actually liberalised, exacerbating the controversy. This paradox stems primarily from the British economy’s dependence on cheap labour, along with the social liberalism of a considerable share of politicians and the British public, an important indicator of which remains openness to immigration.

.png) AA/ABACA / Abaca Press / Forum

AA/ABACA / Abaca Press / Forum

Waves of Immigration after World War II

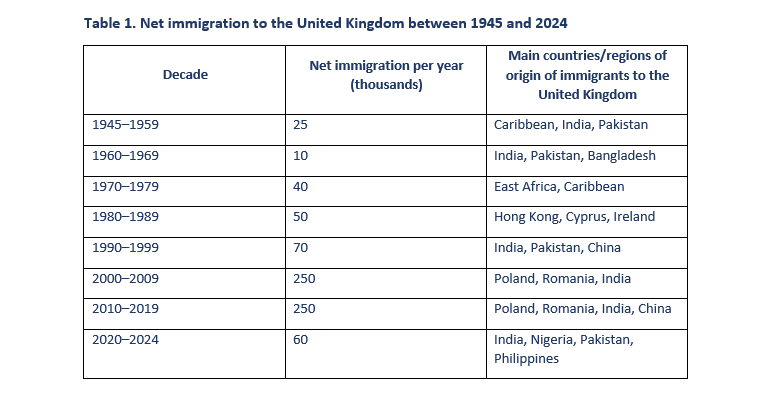

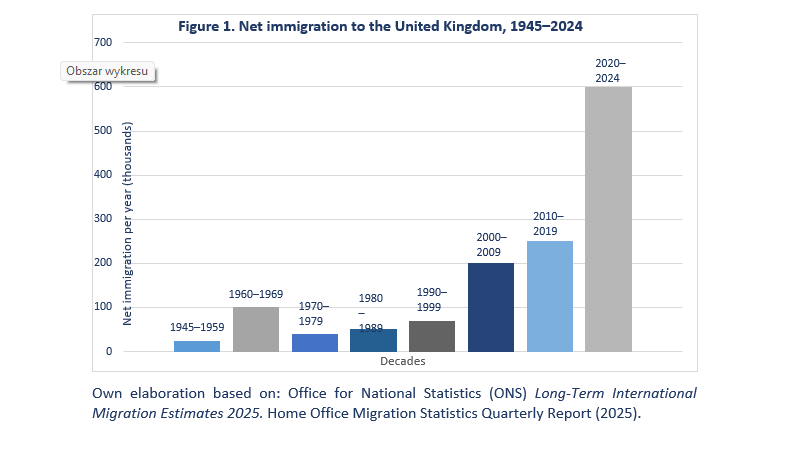

After 1948, the Labour government, responding to post-war labour shortages, created a single legal definition of “citizenship of the UK and Colonies”, which included both Britons and colonial British subjects, and entrenched the right of the latter to enter the UK. This led to mass immigration, in particular from the West Indies (aggregate data on immigration waves between 1945 and 2025 is presented in Table 1 and Chart 1). Although since 1971 citizens of former British colonies have lost their automatic right of entry and permanent residence, the UK’s accession to the European Community in 1973 opened up a n

ew channel for immigration, connected to the principle of free movement of persons.

The second wave of immigration occurred during the New Labour government (1997–2010), when approximately 250,000 people arrived in the country each year, largely from the Middle East and North Africa in connection with British military missions in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya. The Human Rights Act 1998, which enabled British courts to directly apply the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), significantly intensified the influx to Britain of people exercising their right to family reunification or obtaining international protection. In parallel, as a result of the Tony Blair government’s 2004 decision not to introduce a transitional period for the free movement of workers from the EU accession countries to the UK, approximately 4-5 million citizens of the new EU Member States arrived in the UK between 2004 and 2008 (instead of the predicted 150,000). In absolute terms, this category was dominated first by Poles, then by Romanians, and in relative terms, by Lithuanians (under the EU Settlement Scheme, aimed at EU citizens wishing to obtain leave to stay in the UK in the face of Brexit, approximately 322,000 Lithuanian citizens registered, i.e., approximately 10% of its population).

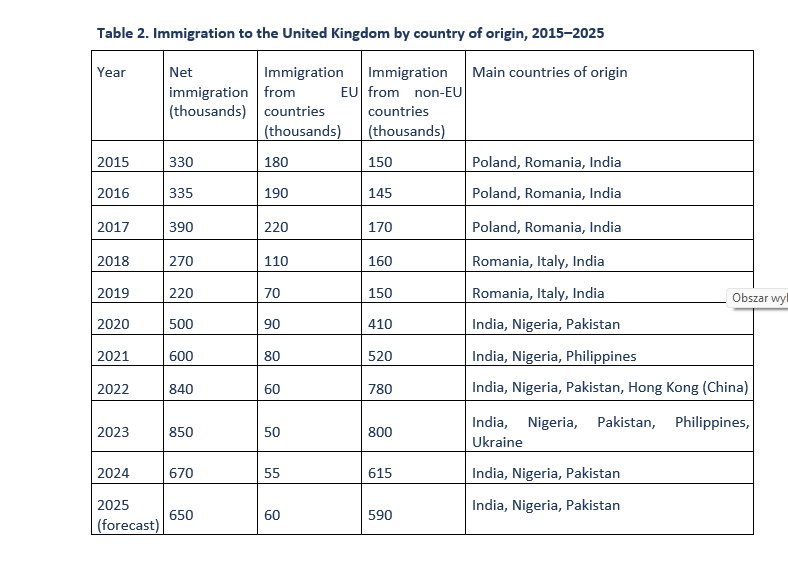

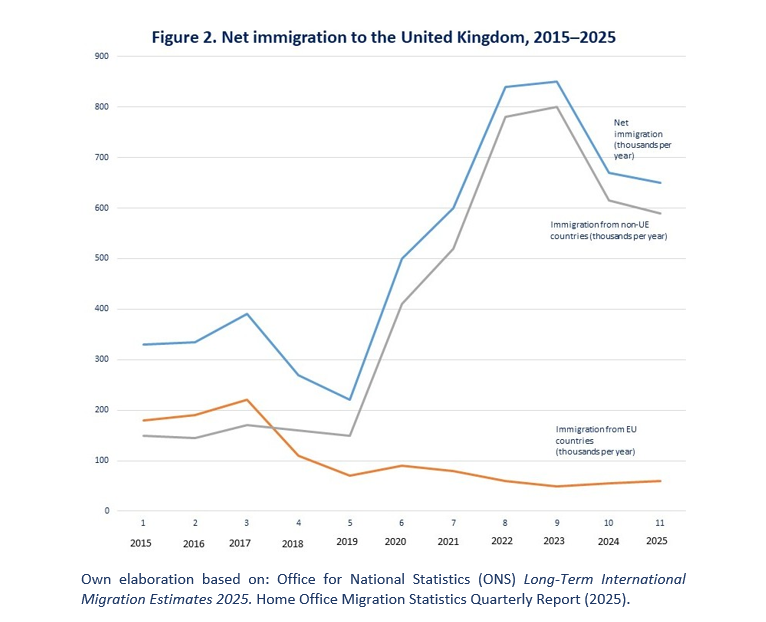

The third, most intense wave of immigration occurred after Brexit. It was mainly motivated by economic considerations. Between 2020 and 2024, it reached approximately 500,000–900,000 people per year net (i.e., taking into account data on emigration from the UK), mainly from India, Nigeria, Pakistan and the Philippines. At the beginning of this wave, according to the 2021 census, people of immigrant origin accounted for approximately 25% of the UK population (of whom 68%, or 17% of the total population, were born abroad). In the three largest cities: London, Birmingham and Manchester, White British people (classified by the Office for National Statistics as English, Scottish, Welsh or Irish) were in the minority.

Challenges Related to Social Integration

Until World War II, British society was one of the most ethnically and culturally homogeneous in Europe. However, over the next few decades, it became one of the most diverse. From a contemporary perspective, the first great wave of immigration was characterised by a high initial level of cultural integration, and a significant proportion of those who arrived in the UK at that time were veterans of the British or Allied armed forces from the times of the Second World War (coming from the then British dominions and colonies, or from Poland, Czechoslovakia and other European countries). Nonetheless, at that time, this wave represented a fundamental change in British social, political and economic life, and was accompanied by ethnic and racial tensions and riots (e.g., in London’s Notting Hill in 1958). This resulted in the parallel introduction of anti-discrimination legislation, and the tightening of criteria for granting entry and residence permits.

Another qualitative change came with the second great wave of migration at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries. It was accompanied by a transition from the model of British cultural dominance to a model of multiculturalism and the withdrawal of the requirement for full linguistic and cultural integration of newcomers. As a result of rapid changes in the ethnic and religious composition of British society, the problem of self-isolating ethnic and religious communities, within which alternative normative systems operated (e.g., the development of a service sector advertising itself as compliant with Islamic religious law), began to emerge and gradually grow. Paedophile gangs composed of Muslims of Pakistani origin with a strong tribal/clan identity became a symbol of pathologies arising from this situation. These criminal organisations operated mainly in (post-)industrial towns in northern England and the Midlands, where the above-mentioned ethnic/national groups often constituted local majorities. In the context of problems with the social integration of immigrants, the key factor was the selection of victims by these criminal groups according to religious and ethnic criteria. Furthermore, after the attacks in the US in 2001 and in London in 2005, Islamic extremism replaced Irish nationalism as the primary source of terrorist domestic threats in the UK.

The uneven distribution of the benefits and costs of immigration in the UK, both on geographical and class bases, combined with the problems of social integration of some immigrants (or their descendants), led to a profound erosion of support for the multicultural model across British society. Against this backdrop, the third wave of immigration accelerated changes directly affecting the functioning of the political system. Key from this point of view is the intensifying phenomenon of political campaigns based on ethnic and religious criteria, which are beginning to fundamentally change the traditional political scene. For example, in the 2024 parliamentary elections, independent MPs representing the pro-Palestinian movement gained representation on a par with the Reform UK party, which at the time enjoyed the third highest level of public support. As a result of this phenomenon, two members of the Labour Party’s Shadow Cabinet did not make it into the House of Commons in the 2023 General Election, and several of today’s ministers found themselves on the verge of losing their parliamentary seats (including Jess Phillips, as minister responsible for investigations into the aforementioned paedophile gangs).

There has also been a steady increase in the number of incidents and protests against the UK’s internal asylum seeker relocation system, introduced in 2021. Since that point, the UK has increasingly relied on dispersing asylum seekers after they illegally cross the French-British maritime border in small boats. Initially housed on barges and in former military bases, these persons then began to be housed in homes rented on the open market (contributing to the displacement of British citizens from the rental market) and hotels (generating daily costs of £5.5-6 million between 2023 and 2025). The creation of such centres took place with minimal local consultation.

In 2023-25, cases of sexual violence committed by people living in refugee centres against local residents, which were widely reported in the traditional and social media, became a problem (the conviction in September 2025 of an Ethiopian man for an attack on a British minor in Epping was particularly widely reported). From the point of view of social cohesion, a turning point was the riots in many communities across Britain, triggered by reports of a knife attack by a person of immigrant origin on very young schoolgirls attending a summer dance school in Southport in July 2024. The riots highlighted the crisis of social cohesion and deepening frustration. High levels of tension continue, fuelled, among other things, by a knife attack on a synagogue in Manchester on Yom Kippur in October 2025. In the public consciousness, immigration has become a symbol not only of pressure on infrastructure, but also of broader concerns about the country’s civilisational and national identity and internal security. In the first half of 2025, there were several dozen major protests in individual British cities. In addition, in September this year, a march against immigration (under the “Unite the Kingdom” slogan) was organised in London, with an estimated 250,000 participants. It was the first event of this scale organised by activists commonly associated with the Far Right, which was nevertheless widely discussed in the mainstream media and reportedly attended in numbers by representatives of the middle class, normally the bastion of liberal attitudes in British society.

Immigration Policy and the British Economy

Since 2004, the mass importation of low-cost labour has become a pillar of the British economic model. Immigrants filled gaps in industry, construction and services, and over time also in care, catering and transport. In 2023, foreigners accounted for about 20% of the workforce and contributed over GBP 8 billion to the economy. This system has sustained economic growth, but at the same time, it perpetuates a model of low wages and limits (or even reverses) automation and the development of domestic workers. The benefits of immigration have been concentrated in cities and sectors dominated by big business (especially multinational corporations), while the social costs have been disproportionately borne by peripheral regions, reinforcing territorial inequalities.

In the first and second decades of the 21st century, immigration from the then-new EU countries was also a source of socio-political problems. Among other things, it caused the debate on immigration policy to focus on the issue of free movement of persons within the EU as an obstacle to changing the UK’s policy towards third countries. Although the issue of immigration from third countries was never within the EU’s competence during the discussed period, the argument that attempts to restrict immigration from outside the EU were pointless, given that the EU’s freedom of movement meant that essentially unlimited numbers of citizens from the new EU countries could come to the United Kingdom, was widely used in British political debate. There was also strong opposition among some sections of British society to the transfer of wages and social benefits from the UK to the then-new EU Member States, as well as problems in prosecuting people who committed crimes in the UK and then returned to their country of origin. These issues played a major role in building public support for Brexit, especially in the context of the aforementioned rhetoric linking the issue of free movement of persons within the EU and the migration crisis in the Union’s South-Eastern neighbourhood in 2014-2016.

Immigration as a political and electoral issue

In 2016, the slogan of “taking back control” of the borders became one of the two most prominent elements of the Brexit campaign. As a result, in 2017, Theresa May’s Conservative government began work on a new points-based system, modelled on the Canadian and Australian systems, which was finally introduced in 2020 by the Johnson government. In theory, the new system was supposed to favour highly skilled migrants, primarily through high language, professional and income thresholds. However, as a result of the British labour market's systemic dependence on the import of cheap labour and fears of a slowdown in the economic recovery after the COVID-19 pandemic, the Johnson government decided in 2021 to significantly reduce the minimum wage requirements that immigrants had to obtain from their British employers (i.e, their income thresholds), especially for people in shortage occupations (e.g., in the medical and care sectors).

This liberalisation (commonly referred to as the “Boriswave”) led to record inflows of migrants between 2021 and 2024, which stabilised the labour market but at the same time further limited productivity and wage growth. Socio-economic problems were then exacerbated by the development of an illegal labour market based on people entering the UK legally but then overstaying their visas, and subsequently, immigrants arriving and residing in the UK illegally. Based on estimates from a journalistic investigation by The Spectator magazine, based on data on water consumption and sewage production in households, the underestimation of the number of immigrants nationwide at the turn of 2024-2025 was estimated at 1 million people.

In response to growing public discontent, Rishi Sunak’s Conservative government, in the run-up to the 2024 parliamentary elections, raised the work visa income threshold from £23,000 to £38,700 (effective from 2025) in an attempt to limit the influx of low-skilled immigrants. At the same time, work began on an electronic travel authorisation (ETA) system, equivalent to the EU's EES system, which was intended to strengthen border controls and symbolically confirm the regained sovereignty after Brexit, and was finally introduced between February and April 2025. However, these measures did not resolve the paradox of the British economic model, which is that political pressure to restrict migration clashes with the economic need to maintain it. Immigrants have become indispensable for the functioning of public services and maintaining growth, but at the same time, they remain a source of social tensions that currently co-determine the British political scene.

In recent political campaigns (the 2024 General Election and 2025 local elections), the issue of migration dominated the debate. The Conservatives called for tighter regulations, the Labour Party for a balance between market needs and border control, while the Liberal Democrats and the Greens advocated a more open approach. Nigel Farage’s Reform UK party also had a significant impact, gaining support with its slogans of withdrawing from the ECHR and taking back full sovereignty. Since the 2024 General Election, public sentiment has remained clear: according to surveys, 70-80% of Britons are in favour of restricting immigration, including the majority of Labour Party voters. The debate has shifted from the idea of multiculturalism to the concept of a multi-ethnic, yet culturally cohesive society. As a result, migration policy has become a battleground between the parties and a litmus test of the government’s ability to restore public confidence.

The Labour Government's Immigration Policy

Keir Starmer’s government, formed in July 2024, inherited from its Conservative predecessors a crisis of credibility over immigration policy. The new cabinet had to reconcile three conflicting goals: maintaining growth in an economy dependent on migrants, reacting to social pressure, and complying with human rights standards.

In April 2025, Starmer’s government announced a balanced immigration strategy combining intentions for control and economic pragmatism. The previously-mentioned income threshold of £38,700 was maintained, along with restrictions on family reunification and student visas, while seasonal visa programmes in agriculture and construction were expanded. The reformed Immigration Advice Authority is an advisory body to analyse labour market needs and set annual visa quotas. The government’s strategy is intended to be technocratic and based on economic data. The aim is to ensure the stability of the system and rebuild public confidence without radically changing the direction of this policy. The government is trying to avoid extremes: it is limiting the influx of people in low-paid sectors, but remains open to immigration in key demand areas.

The Labour Party is also trying to regain control of the language of public debate. The rhetoric of fair migration is intended to neutralise Reform UK’s slogans and minimise social divisions. Efforts in the latter field are marked by internal contradictions, illustrated by the Prime Minister’s assessment of the United Kingdom as an “island of strangers” in his May 2025 speech on the impact of mass immigration on social cohesion, a position from which he then demonstratively withdrew under criticism from within his party’s ranks. For several months, Starmer’s cabinet has been losing support among both working-class voters, who expect a reduction in immigration, and the urban electorate, for whom the policy of restrictions is contrary to liberal values. As a result, since May 2025, the Labour Party’s ratings have remained on average at least 10 percentage points lower than Farage’s party (in December 2025, Reform UK polled at 27%, compared to 18% for Labour and 17% for the Tories, according to the Politico Poll of Polls). Despite the British government’s declared balance, the paradox remains: the economy cannot function without migrants, while society demands restrictions on immigration.

Relations with the European Union

On the international stage, Starmer’s government is seeking to restore credibility in its cooperation with the EU and other international organisations, signalling its willingness to re-engage in joint migration management and youth mobility programmes. However, it remains cautious about any agreements that could be perceived at home as reintroducing “EU free movement through the back door”.

The EU-UK Strategic Partnership Agreement, signed in May 2025, opened a new phase of cooperation after Brexit. One of its key elements is the Youth Mobility Scheme, which allows people aged 18-35 to stay, study and work temporarily on both sides of the English Channel. For the EU, the programme would have symbolic significance as a way of restoring the social and professional ties severed by Brexit. For the UK, it would potentially be a tool for attracting talent and filling gaps in the labour market without formally returning to the principle of free movement of persons.

However, the implementation of the scheme faces serious political barriers. Anti-immigration sentiment and strong support for restrictions persist in the UK, reinforced by the rhetoric of Reform UK. Meanwhile, stays by young Europeans lasting longer than nine months would count towards British immigration quotas. An additional challenge is the dispute over EU participants’ access to British social, medical and educational benefits (e.g., reduced domestic university tuition fees) in the context of the inefficiency of British systems, which makes liberalisation politically risky. Finally, another challenge is the asymmetry of commitments: while the British government would commit to treating citizens of all EU countries equally, most of the issues covered by the agreement on the EU side fall within the competence of individual Member States, with the possibility of real differences in their approaches towards British nationals.

In terms of perception, the British-EU negotiations on legal immigration policy are also strongly affected by the negative assessment in the British public debate of the quality of technical cooperation on matters relating to the prevention of illegal immigration from the EU to the UK and the relocation of persons arriving from France and other Member States (carried out, among others, through Europol and the Anglo-French “One In-One Out” bilateral agreement assuming relocation of irregular migrants from Britain to France in exchange for the UK accepting asylum holders from France). The review of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) in 2026 and talks on the operationalisation and implementation of the EU-UK strategic partnership (by 2027) will test whether the free movement of persons between the EU and the UK will become an area of convergence or remain a source of tension.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The UK’s experience shows that the lack of a coherent migration strategy combining economic, social and political objectives leads to a loss of public trust and political instability. For decades, successive governments have treated immigration as a tool to alleviate labour shortages, ignoring its social and regional impacts. Liberalisation of regulations, unsupported by effective integration and public communication, has led to an erosion of trust in the state, a rise in populism and a lasting division in society.

The British situation should be an important source of lessons for Poland and other EU countries. The most important of these is the need to develop a comprehensive and long-term immigration policy. The lack of such a comprehensive policy in the UK has resulted in the economy becoming overly dependent on cheap, imported labour, very low investment in domestic human capital, inconsistent public communication and reactive decisions made under the pressure of electoral sentiment. Equally important were the shortcomings in housing policy and public services, which have failed to keep pace with the rapid population growth driven by immigration.

From the European Union’s point of view, it is important that the rise in popularity of Reform UK may weaken the British government’s negotiating mandate on reopening the labour market and education to EU citizens under the age of 35. The medium-term challenge therefore remains maintaining mobility as a source of EU-UK cooperation rather than political conflict. The creation of a joint coordination mechanism between the European Commission and Member States and the UK Home Office would allow for the maintenance of a transparent recruitment system for participants in the youth exchange programme and the ongoing monitoring of population flows. In the longer term, the programme could be incorporated into the Erasmus+ system or constitute a separate module financed from the EU-UK strategic partnership budget.

An important direction for the development of cooperation is to combine mobility with competence partnerships. Joint EU-UK training centres, particularly in the fields of new technologies, renewable energy and healthcare, could become a permanent platform for the exchange of knowledge and experience. These initiatives should be financially supported by the European Social Fund Plus, which would ensure their stability and long-term effects. At the same time, it is worth developing professional exchange programmes that would address skills shortages in both economies.

For Poland, the key observation is the need to maintain a balance between labour market needs and the state’s capacity to integrate migrants. Unlike the United Kingdom, which has built a low-wage economy based on immigration, Poland should invest in education, innovation and automation. A responsible migration policy requires linking population inflows to the potential of local labour markets and infrastructure planning. The concentration of immigration in large agglomerations, as in the United Kingdom, risks social tensions and the marginalisation of more peripheral regions.

Consistency in political messaging is equally important. In the British experience, the disconnect between the political rhetoric of full control and the liberal practice of policy has deepened social disappointment and strengthened populism. Poland should base its migration debates on data and analysis, avoiding the instrumental use of this topic in election campaigns. Controlled migration, supported by transparent communication, promotes social stability and economic confidence.

An important element of Polish domestic policy should be to support the return of skilled migrants from the United Kingdom. Poland could develop existing reintegration programmes financed by EU funds, creating a platform connecting returning specialists with domestic companies. This solution would allow the experience and skills gained abroad to be used for the development of the domestic labour market.