Member States Seek to Unmask Russian Espionage in the EU

Russian intelligence services are actively developing their networks of spies in the EU. While Member States are trying to counteract this and are undertaking coordinated action, many of them have limited operational capacities. Their cooperation at the EU level is hampered by differences in threat perceptions and a lack of mutual trust. With the aim of developing common competences, EU diplomacy can inform Member State societies about the growing scale of espionage threats by publishing regular reports on this subject.

Axel Bueckert / imageBROKER / Forum

Axel Bueckert / imageBROKER / Forum

In response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, EU states, which retain national security competences, have taken unprecedented steps to curb Russia’s espionage. As part of these activities, since February 2022, they have expelled around 490 Russian diplomats from the EU territory, out of which the majority have been considered to be intelligence officers or their associates. A significant number of diplomats were expelled from Bulgaria (70), Poland (45), France (41), Germany (40), Belgium (40, including 19 accredited to the EU), Slovakia (38), Slovenia (33), Italy (30), and Spain (25). This is in line with the trend of increasingly frequent public identification and sanctioning of Russian spies in the EU, which has been noticeable since 2018. At that time, in relation to the failed attack by Russian services on the former spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter in the UK, some Member States expelled around 70 Russian diplomats from the EU.

Characteristics of Russia’s Activities

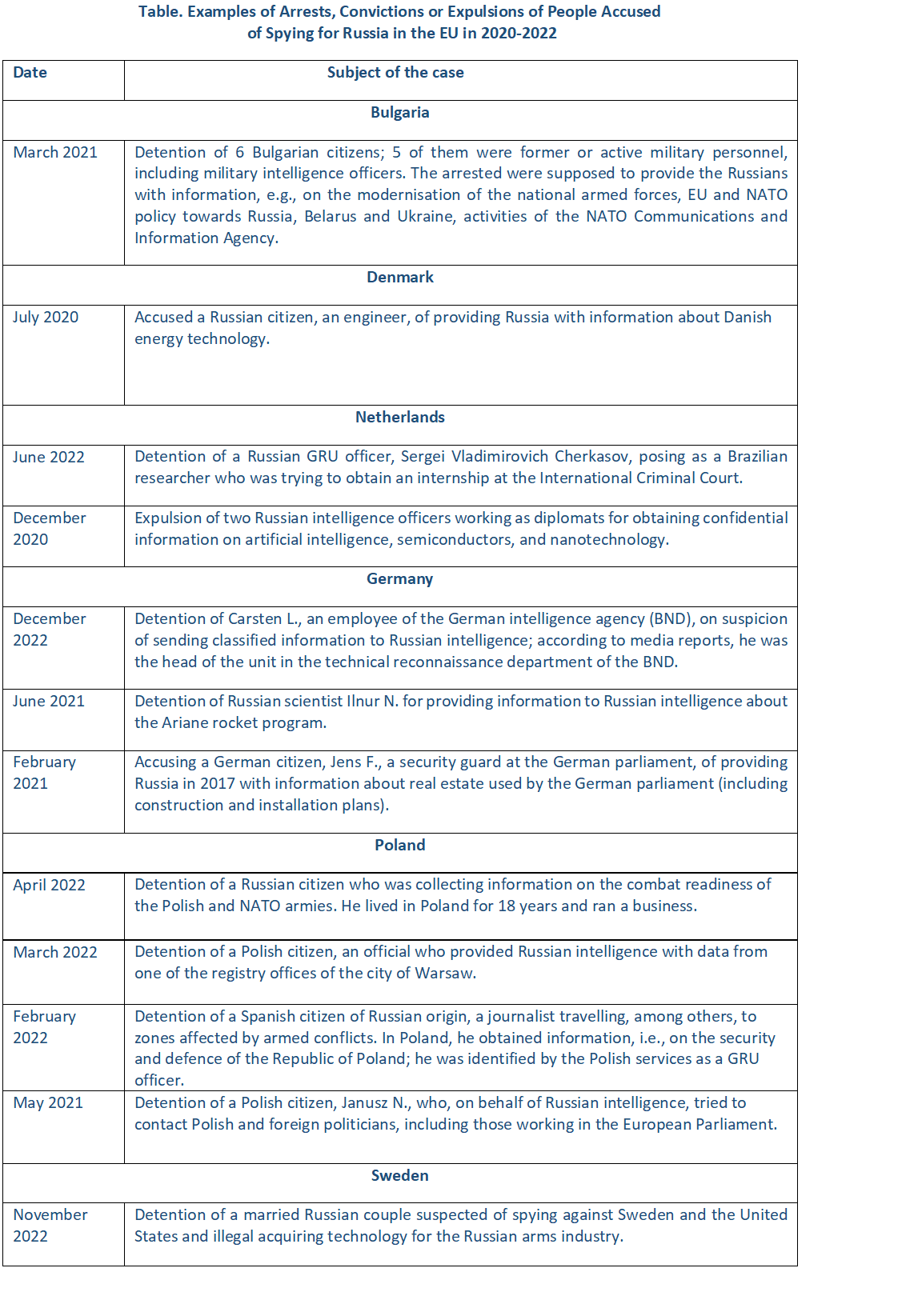

By pursuing a confrontational policy towards the West, Russia has been intensifying its intelligence activity in the EU for at least a decade in order to increase the effectiveness of its foreign policy, strengthen its military and technological potential, and carry out operational tasks in the EU, such as attacks or sabotage. Russian services try to obtain classified information in Member States’ security and political situation, critical infrastructure, technology, civilian data (e.g., on Russian dissidents), as well as on the EU and NATO (see table below). Although the activities of Russian intelligence cover the territory of the entire EU, its spies are particularly active in countries where NATO infrastructure and the headquarters of international institutions are located. The cases of espionage identified so far by counterintelligence and investigative journalists (i.e., Bellingcat) concern, for example, EU and NATO institutions in Belgium (Brussels), a NATO base in Italy (Naples), or NATO military exercises in the Baltic states. With the invasion of Ukraine, of particular interest to the Russian services are issues related to EU and NATO relations with the attacked country, including military assistance provided to it (e.g., transport routes of arms deliveries, exercises) and technologies to which Russia has limited access due to sanctions.

Russia conducts its intelligence activities in the EU through many institutions, the most important of which are military intelligence (GRU), the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), and the Federal Security Service (FSB). They have high operational capabilities, for instance it is estimated that SVR alone employs at least 13,000 people. The Russian services are gradually developing cyberespionage, but their functioning is still based on the classic methods of obtaining classified information using an extensive network of spies. It mainly includes officers working as diplomats because diplomatic immunity allows them to avoid criminal proceedings, and in the event they are unmasked, they risk only being considered persona non grata and expelled. According to the available assessments of the EU intelligence services, a significant part of Russia’s diplomatic corps in the Member States are spies. In 2021, Swedish intelligence estimated that a third of Russia’s diplomats working in the country were intelligence officers. Many of them are in place to recruit informants, and one officer can maintain 3-5 contacts at a time. Spies can also operate in the target country without diplomatic immunity, usually Russian citizens operating under cover as so-called “illegals” under false identities. Russian intelligence recruits as agents foreigners who have access to classified information (e.g. officials, military personnel, journalists or analysts of research institutions). They often recruit these spies on Russian territory from a select group of regular visitors who express a positive or neutral attitude towards the Russian authorities and are able to perform intelligence tasks. Russian services also recruit foreigners to perform operational tasks, including observation of military and critical infrastructure (e.g., sailors to monitor ports).

Challenges for the EU

Some Member States, while pursuing a favourable policy towards Russia, do not take publicly visible actions against its spies. This results, among others, from their assessment of security threats and the scale of economic ties with Russia. Cyprus, Malta, and Hungary have not expelled any Russian diplomats after the invasion of Ukraine, and at least 50 of them remain on Hungarian territory. The Austrian authorities expelled just four diplomats, while about 60 are still accredited in this country. The mere removal of Russian intelligence officers acting as diplomats does not paralyse the activity of Russia’s intelligence services, but it hinders it. It should be kept in mind that the Russian spies remaining in EU countries may operate throughout the Schengen area and develop a network of contacts. In the years 2010-2021, 59 proceedings against EU citizens regarding the provision of information to foreign intelligence took place in Member States, resulting in 42 people convicted (Swedish Defence Research Agency data). Most of the cases concerned espionage for Russian intelligence, and nearly two-thirds of the incidents took place in the Baltic states and Poland. After the Russian invasion, the number of proceedings increased only in some countries. Although initiating legal proceedings is just one method of combating espionage, it is important as it increases public awareness of, among others, potential penalties related to cooperation with third-country intelligence.

Although it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of the Member States’ counterintelligence services due to the secrecy of their functioning, their operations may be limited by insufficient human resources in some countries. While several EU members such as the Netherlands and Belgium plan to increase the budget and staff of counterintelligence services or tighten legislation after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the capabilities of EU members in this area vary. Beside extensive intelligence and counterintelligence services in France (which has about 13,000 personnel, including about 3,800 in counterintelligence) and Germany (about 10,400 at the federal level, including about 1,100 in military counterintelligence), other countries have much smaller human resources—Spain, about 6,500, Sweden, about 2,700, the Netherlands, about 2,300, Belgium, about 1,200 (data from the Fundamental Rights Agency and other sources). Some countries rely on information provided by non-EU allies, including the U.S. and the UK.

The multilateral operational cooperation of Member State services in the EU is limited by the fear of possible infiltration of the intelligence services of one or more countries and the need to protect sources of information. While there is a mechanism at the EU level for Member States to exchange classified information on a voluntary basis under the EU Military Staff Intelligence Directorate and the EU Intelligence and Situation Centre (EU INTCEN), they make limited use of this arrangement. EU countries prefer bilateral cooperation and direct exchange of information with allies. In order to identify Russian spies, Estonia cooperates with other countries, for example, those bordering Russia. Countries with advanced intelligence technologies also prefer to cooperate with counterparts with similar potential.

Conclusions

The cases of Russian espionage detected so far in the EU confirm that Russia manages to place spies in strategically important institutions of the Member States (see table below). Despite the reduction in the number of intelligence officers working under diplomatic cover in 2022, Russia still has great potential to conduct espionage activities due to, among others, the different Member State policies. Given the long-term nature of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the resulting international sanctions, its activity will only intensify. To counteract this, it is necessary to strengthen counterintelligence capabilities in the EU. In order to raise public awareness of the scale of espionage by third countries, including Russia, in the EU, the European External Action Service could consolidate information on such incidents and ongoing investigations, identify foreign intelligence interests and losses suffered by the EU, and make this information available on a regular basis in the form of reports. In cases where further Russian diplomats are identified as spies, Poland could also encourage EU countries to coordinate further expulsion of Russian diplomatic corps from EU territory.