Georgia's Parliamentary Elections to be a Check of Direction

The most important political event in Georgia this year will be the parliamentary elections, scheduled for October. The unofficial pre-election campaign is already underway. Both the Georgian Dream party, which has been in power for three terms, and the current opposition are likely to win the most votes. The latter has the prospect of forming a coalition government. It also wants the upcoming elections to be a kind of referendum on the long-standing rule of the Georgian Dream and will try to convince voters that what is at stake is the direction of Georgia’s development—either with Russia or the West.

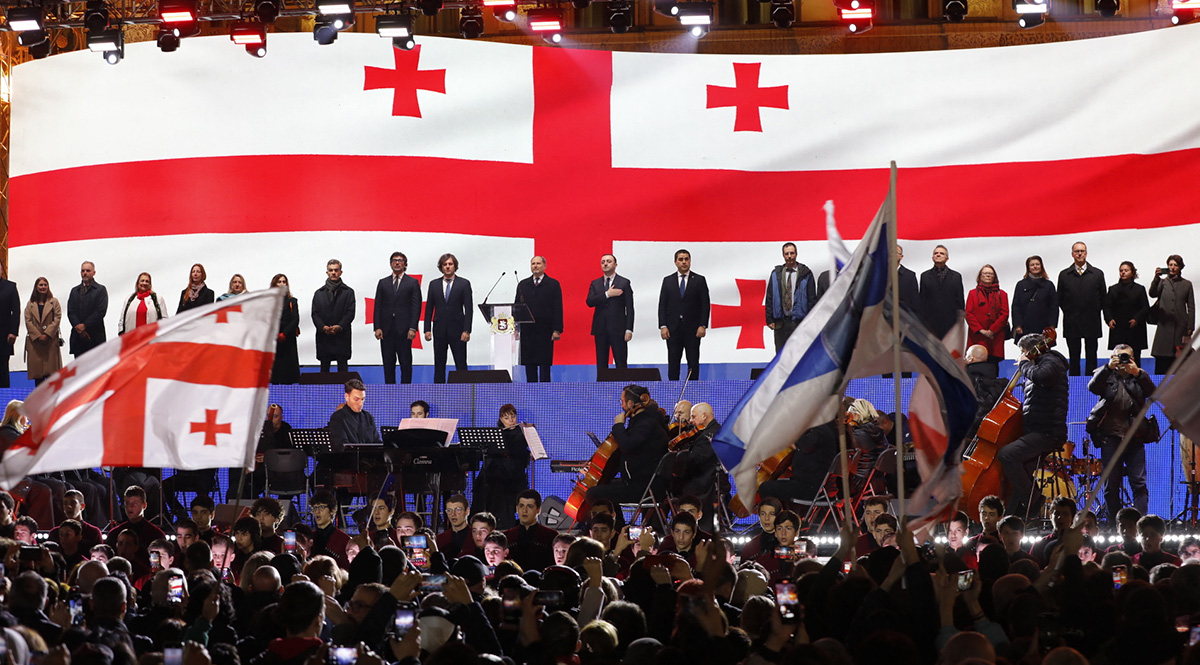

AA/ABACA / Abaca Press / Forum

AA/ABACA / Abaca Press / Forum

The Ruling Party

After 12 years in power, Georgian Dream (GD) has a good chance of winning its fourth consecutive parliamentary election. In polls, the party in power has about 35-55% support. This gives the ruling party the probability of victory in the elections but does not guarantee a parliamentary majority, which will depend on whether smaller opposition parties manage to cross the 5% electoral threshold. If not, the ballots cast for them—so-called wasted votes—will mostly be awarded to the winning party, thus securing it further seats. At the same time, GD’s chance of retaining power may also come from the ruling party's support during the electoral campaign of minor, anti-Western political forces, which, if they cross the electoral threshold, could become coalition partners with the ruling party.

An important factor that may persuade voters to keep power in the hands of the GD will be a programme for the upcoming elections that attracts new voters and mobilises its consistent backers to go to the polls. So far, the ruling party has not presented any new proposals, though. Formally, the election campaign has not yet begun, but part of the GD’s messaging seems to be aimed at frightening voters with the return to power of the main opposition party, the United National Movement (UNM), and to exaggerate its abuses. This task will be taken up by Bidzina Ivanishvili, an oligarch, founder of GD, and former prime minister who recently announced his return to Georgian politics. His re-engagement is indicative of the ruling camp’s level of fear of losing power and linked to the release of former president Mikheil Saakashvili and the holding of GD to account by a possible new government.

The Opposition

Despite GD’s lead in polls, the opposition has a real chance of seizing power. The pro-Western opposition parties enjoy a combined level of support nearly equal to the ruling party. The largest of these, the UNM, should receive about 15-25% of the vote. So far, the UNM has entered into an electoral agreement with the grouping Strategy Agmashenebeli (2-4%) under the name Winning Coalition. However, in order to even think about a good electoral result, these forces must forge a new and capable leader. The current one, Levan Khabeishvili, is a politician lacking charisma and political relevance. Another limiting factor in maximising support for UNM is the constant reports about Saakashvili’s release and the possibility that he could be a candidate for prime minister of a coalition government. Saakashvili, though, has a high unfavourable ratings and is deemed unacceptable as a future prime minister to the other opposition leaders.

The other pro-Western parties are verging on the electoral threshold. In the upcoming elections, parties will formally not be allowed to form electoral coalitions, a new measure deliberately introduced by the GD to make it more difficult for the fragmented opposition to challenge it. To circumvent this restriction, several parties will run on one list and under the banner of a single grouping. Agreement on the shape of such alliances may be difficult due to the fight for seats on the electoral list or the subsequent distribution of subsidies. However, to take power, the opposition will have to run on not more than three electoral lists to minimise the risk of individual parties failing to cross the 5% electoral threshold.

The President’s Role

Salome Zurabishvili, the president of Georgia who has not ruled out running herself for parliament, could become a key factor in the elections. It would mean she must step down as the head of state a few months before the end of her term (end-2024). She could either form her own party or act as the patron of an alliance of several existing opposition parties, led by the For Georgia grouping (some opposition forces are reluctant to back her, above all the UNM).

An important power at the president’s disposal and one she can use during the campaign is the right to pardon Saakashvili. So far, she has avoided explicit declarations on this issue. Releasing the former president from prison could be a mixed exercise, however, because it would exacerbate the political conflict between the GD and the opposition and cause tensions within the opposition itself.

Contentious Topics

The election campaign is likely to be about improving the living standards of Georgians—fighting unemployment, increasing salaries, and economic development. The second main focus will be on foreign policy, in particular the question of the start of Georgia’s accession talks with the EU and the future of relations with Russia. The opposition will try to portray the elections as a civilisational choice for Georgians, accusing those in power of being pro-Russia and lacking real interest in the country’s integration with the West. The third area will be the state of Georgian democracy and the rule of law. The opposition accuses the GD of authoritarianism and persecution of civil society representatives and media. These topics already resonate in Georgian public opinion and the dispute will only grow as the election date approaches.

Those in power, in turn, will remind Georgians about their initiatives, including the introduction of universal health insurance, actions to allegedly prevent Georgia’s entanglement in a new war with Russia, gaining candidate status for EU membership, and overseeing high economic growth (over 10% in 2022, an estimated 7% last year). In addition, GD announced the continuation of past actions (multi-vector foreign policy, starting accession negotiations with the EU, pragmatic relations with Russia, strengthening relations with China, continuing mediation between Azerbaijan and Armenia, investment in infrastructure, sustaining high economic growth), warning that a possible change of power will bring destabilisation to the country. Opposition parties, on the other hand, will emphasise in their programmes the need to accelerate efforts to integrate Georgia into the EU and NATO, strengthen relations with the U.S., limit Chinese involvement in the development of Georgia’s infrastructure, contain Russian influence (introducing visas for Russians, restrictions on Russians buying property and starting businesses), economic reforms, as well as restoring democracy and the rule of law.

Conclusions and Outlook

Current polls do not give a clear answer to the question of who will win the upcoming elections. The GD is more likely to retain power than the opposition is to take it over. This is supported by the country’s good economic situation, the control of administrative resources by those in power (budget, state apparatus), and the return to politics of the real leader of the power camp, Ivanishvili, who the GD electorate associates with electoral success and effectiveness. The opposition can count on success if it mobilises its existing voters, reaches out to new ones, and forms electoral alliances (several parties running on the list of one of them).

The task facing both those in power and the opposition is to persuade the undecided majority of Georgian society to their side. Georgians have a similar aversion to the GD as to the opposition. A positive electoral programme from both political camps, as well as, in the long term, the emergence on the Georgian political scene of new charismatic politicians able to mobilise the electorate, could change the situation. However, the rise of a new political force is not expected before the elections.

In view of the upcoming elections, the GD will not take real steps to implement the recommendations of the European Commission (EC) regarding accession negotiations with the EU, as this would damage its chances of retaining power. The GD’s cautious policy towards Russia and the Russian invasion of Ukraine also is not expected to change unless the situation on the frontline swings decisively. The opposition will criticise the ruling camp for this and will try to portray itself as the force ensuring a real pro-Western direction for Georgia and future membership in the EU and NATO.

Both Poland and the EU may consider sending a very large group of observers, both for the long and short terms, to Georgia. Among their tasks would be to monitor the course of the election campaign, as well as the vote itself, in terms of meeting democratic standards (one of the EC’s requirements for the opening of Georgia's accession negotiations with the EU). In addition, Poland and the EU may consider the possibility of constantly encouraging the Georgian authorities to implement the reforms included in the list of nine recommendations made by the EC after Georgia was granted membership candidate status in December 2023.

.jpg)

.jpg)