EU Still Weighing Russian LNG Ban

As part of the next sanctions package, the European Commission (EC) does not envisage a ban on Russian LNG imports, although its sales to the EU since 2022 have been growing steadily. Adoption of a ban is necessary to make it more difficult for Russia to finance its war with Ukraine. It is also advisable in order to implement the RePowerEU plan to move away from Russian energy resources by 2027. The imposition of sanctions is supported by the situation on the global LNG market, the recent U.S. restrictions on the Russian energy sector, and the Trump administration’s announcement to increase American LNG exports to the EU.

.png) Kyodo/MAXPPP / MAXPPP / Forum

Kyodo/MAXPPP / MAXPPP / Forum

Despite the stated ambition to further the RePowerEU plan, the EC did not propose an embargo on Russian LNG in the 16th sanctions package. The reason was said to be the opposition of some countries due to low gas stocks, high consumption in the face of cold weather, and the upcoming elections in Germany. An import ban would reduce the incomes of Russia and its elite, which are financing, among other things, the war against Ukraine and hybrid operations against NATO countries, and in the long term would block the development of the Russian LNG sector.

Russia’s LNG Sector beyond 2022

Russia has been seeking to increase its share of global LNG exports for years and, as part of its 2021 strategy, aspires to increase production to 80-140 million tonnes in 2035 (the global industry leader, the U.S., exported 87 million tonnes in 2024). She sees LNG as a promising source of export revenue, recognising technology developments and global economic trends reinforcing the role of gas as a transition fuel for the energy transition. The authorities’ support for the development of the sector in Russia was also influenced by concerns about overdependence on gas sales to the European market and the risk of a gradual reduction in imports by EU countries, which materialised after 2022 with the collapse of pipeline exports.

Contrary to plans, Russia has failed to reach a production capacity of 45-65 million tonnes of LNG per year by the end of 2024; it has been around 33-35 million tonnes for the past three years. The main reason is Russia’s dependence in the LNG sector on external technologies and contractors and its inability to develop its own solutions. As a result of Western sanctions (mainly the U.S.) adopted since 2022, most Russian investments in LNG infrastructure have been halted or suspended. One example is Gazprom’s Baltic LNG project in Ust-Luga, which has been delayed and will not start until 2028 instead of 2024 at the earliest, with a planned capacity of 13 million tonnes per year instead of 20. Other projects scheduled for completion in the late 2030s such as Arctic LNG-1, LNG-3, Murmansk-LNG, and Obski-LNG have been suspended due to the withdrawal of most foreign partners, including China, caused by sanction risks. Delays in the implementation of the 2021 strategy reduce Russia’s budget revenues (although the exact share is not known for reasons of confidentiality) and raising the cost of projects, which increasingly require, for example, state tax breaks.

Difficulties in developing the logistics—the fleet of icebreakers and ice-class gas carriers (ships capable of transporting LNG in the freezing waters of the Arctic Ocean) necessary for expansion into the Asian market—also remain a challenge. For instance, Novatek’s flagship project Arctic-LNG 2, which partially started exports in spring 2024, currently cannot find buyers, as well as methane carriers, whose sales from South Korea were blocked in 2024 by the U.S. sanctions (South Korea produces 80% of them, China 20%). Until the fleet is expanded, Russia will have to route most of its Arctic exports to Europe, to which transport is possible throughout the season and on average three times cheaper than to Asia. This complicates its efforts to diversify overseas sales destinations and limits future export capacity, making it more difficult to participate in the increasingly important LNG market.

Western Sanctions

A sanctions policy towards the Russian LNG sector has already been in place since 2014 by the U.S., which at the time adopted restrictions on project financing and the export of technical equipment. It aims, among other things, to squeeze Russia out of the competition to increase its share of the LNG market and reduce its budget revenues. The sanctions were extended after the 2022 aggression against Ukraine. The U.S. banned Russian LNG from supplying its territory (such a ban was also imposed by the UK) and then imposed restrictions on entities providing financial, organisational, and technological support to Russian LNG projects (including Chinese and Indian) and a fleet of Arctic icebreakers and gas carriers, among others. These were to block most Russian projects (Arctic LNG-2 was particularly hard hit) and raised the risk of involvement. In January 2025, the outgoing Biden administration dealt a further blow to the Russian industry by including strengthening technological restrictions and extending trade and financial sanctions to more players. This will effectively force Russia to halt LNG exports from its Baltic terminals at the end of February, most of which go to the EU (around 2 million tonnes). There has been little activity on sanctions on Russian LNG from other countries opposed to the aggression against Ukraine; some, such as Japan (to which about 15% of Russian exports go) or South Korea, have not imposed them at all.

EU sanctions on Russian LNG have so far been very limited. As part of the 14th package, the EU banned its re-export and transhipment in the Union in June 2024, but this will only come into force from 26 March 2025. The sanctions prohibit EU entities from investing in and providing services to the Russian LNG sector. Some Member States have taken steps on their own to ban Russian LNG shipments (e.g., Lithuania, Germany). So far, the introduction of the embargo has been blocked by countries benefiting from its imports (e.g., France) and by Slovakia and Hungary, politically more sympathetic to Russia (which do not import LNG from Russia). Due to the favourable situation on global markets, including the prospect of an oversupply of LNG in 2026-28, existing importers have withdrawn their opposition and Slovakia and Hungary are the only ones to insist on a veto. At the same time, Novatek is actively lobbying against the embargo.

EU Countries’ Dependence

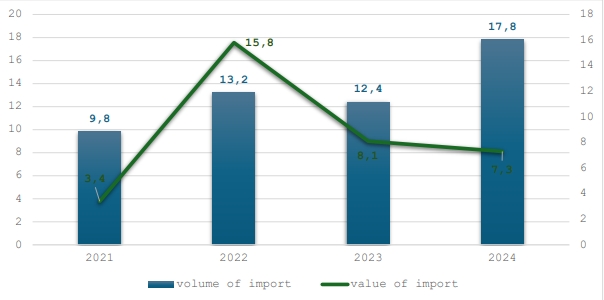

The lack of EU sanctions on LNG imports from Russia, combined with logistical and financial considerations, means that an increasing volume of Russian exports to the Union has been observed since 2022. Between 2021 and 2024, despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, its exports increased from 9.8 million tonnes to around 17.8 million tonnes per year (50% of Russian exports), translating into a share of over 15% of LNG imports to the EU. However, the value, due to the reduction in gas prices, fell from a record €15.8 billion in 2022 to around €7.3 billion in 2024 (Figure 1). The main customers are Spain, Belgium and France, in turn. Up to 25% of the gas is later sent to Germany (where SEFE, formerly Gazprom Germania, is a buyer), part goes to other EU countries (e.g., the Netherlands or Italy), and about 15% is re-exported to China, India and Turkey. Russian LNG supplies to the EU come from the Baltic and Yamal-LNG terminals. They are realised on the basis of long-term contracts, where the most important contractors on the EU side are Spain’s Naturgy and France’s TotalEnergies. Despite the massive exit of EU players from the Russian market after 2022, TotalEnergies still has a 10% stake in the Arctic LNG-2 project and a 20% stake in Yamal-LNG. In addition, some EU entities provide logistics, transhipment, and insurance services for Russian LNG exports.

Conclusions and Recommendations

EU countries should consider imposing an embargo on Russian LNG, leading to the termination of contracts concluded by entities from the Member States. This action could be preceded by sanctions on individual LNG carriers and projects, further reducing Russian export revenues. Reduced LNG imports from Russia could be offset by imports from the U.S. At the same time, this would be an argument in negotiations with the new U.S. administration, which expects an improved trade balance with the EU and announces increased gas exports. The EU could also seek to increase the commitment of other Western countries, including Japan, to reduce cooperation with Russia in the LNG sector.

A success for Poland’s EU presidency would be the adoption of an embargo. In the negotiations within the EU on sanctions, it could be pointed out that they will not lead to an increase in gas prices in the Union and that the current challenges (cold weather and low stocks) are short-term. This is coupled with a favourable outlook for the global gas market, with increasing LNG export capacity in the U.S. and Qatar and relatively low demand in Asia. The unpredictability of Russia as a trading partner and the high carbon intensity of Russian production and its environmental impact are also argued. To change the position of Slovakia and Hungary, it can be argued that the imposition of stronger sanctions on the Russian energy sector will increase the chances of initiating peace talks. It can also be emphasised that there is no economic justification for blocking sanctions in their case because they strengthen Russia’s position and weaken Ukraine’s for political reasons.

Fig. 1. EU Imports of Russian LNG, 2021-2024 (volume in million tonnes and value in EUR billions)

.png)

.jpg)