Afghan Refugees in the European Union: Experiences and Perspectives

For years, Afghans have been one of the main nationalities reported as having irregularly crossed the EU’s external border and applied for international protection on a Member State’s territory. Although the risk of mass migration from Afghanistan to Europe after the Taliban seized power is limited for now, it will increase as the humanitarian crisis in that country grows. There may also be increased migration pressure from Afghans living in third countries. Addressing the problem at its roots will require closer cooperation between the EU and the Taliban to stabilise the state, resume development aid, and create a comprehensive offer for countries hosting Afghan refugees. The Afghan crisis will not, however, bring any breakthrough in the European asylum system negotiations.

Fot. Leonid Shcheglov/TASS/Forum

Fot. Leonid Shcheglov/TASS/Forum

Afghan Refugees in Europe

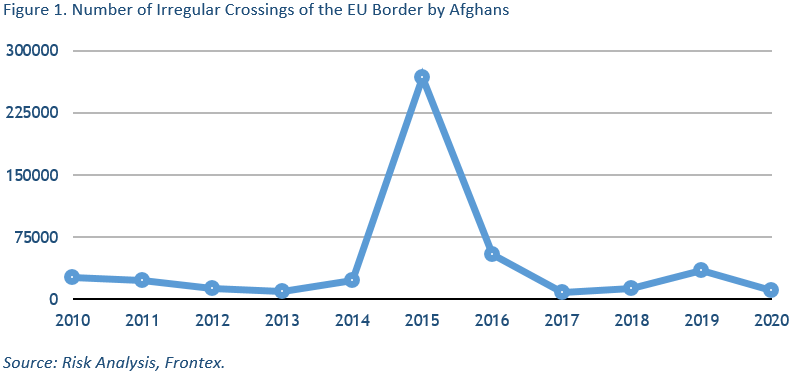

As a result of many years of war, Afghans today constitute the largest group of refugees in Asia and the third-largest in the world, after Syrians and Venezuelans. In recent years, Afghans have frequently been detained after entering the EU irregularly. They most often use the Eastern Mediterranean route, leading through Turkey to Greece. A record increase in the inflow of Afghans was noted during the refugee and migration-management crisis in 2015 when the number of cases exceeded 200,000 (see Fig. 1). In 2020, a total of about 10,000 of irregular migrants from Afghanistan were recorded, which constituted over 8.1% of all attempts to cross borders irregularly. Most of them did not come directly from Afghanistan, but from third countries (mainly Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey) where they had been living for some time. Their migration decisions were mainly influenced by the deteriorating economic and political situations in the host countries.

Afghanistan is also one of the main countries of origin of asylum applicants in the EU. In 2020, applications were submitted by nearly 50,000 Afghans (see Table 1), which made them second after Syrians (70,000 applications) among the largest groups of applicants in the EU. Most applications from Afghan citizens were submitted in Greece (about 11,000), and slightly fewer in France and Germany (about 10,000 each). On average in the EU, half of the applicants from Afghanistan (53% in 2020) have received protection decisions in recent years. The recognition rate of applications varied across the Member States. For example, in 2020 it ranged from 1% in Bulgaria to 93% in Italy in the first instance. At the same time, the large number of people awaiting consideration of their cases should be noted. At the end of June 2021, of the 703,000 asylum applications still pending in EU countries, 82,000 were filed by Afghans (most in Germany and France).[1]

Member States tried to return Afghans who had not been granted protection. In October 2016, at a donors conference for Afghanistan in Brussels, the EU concluded a legally non-binding readmission arrangement with Afghanistan to facilitate the return of Afghans to their homeland, titled the “Joint Way Forward on migration issues” (JWF). A classified document prepared by the Commission and the European External Action Service (EEAS) in March 2016 set two EU migration goals: 1) reduction and control of migration from Afghanistan and Afghan refugees from Pakistan and Iran to Europe; 2) enabling the returns of Afghan migrants and creating a friendly environment for returns in Afghanistan.[2] The EU wanted to return around 80,000 people to Afghanistan, and a package of development aid was supposed to persuade the Afghan government to improve cooperation in this area.[3] As a result, some of the assistance funds were allocated to supporting voluntary returns of Afghans and launching programmes for the reintegration of returnees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). Therefore the case of Afghanistan demonstrated that the EU “narrowly focuses on short-term returns of migrants as a condition for development assistance”.[4] This was seen as an example of the “instrumentalisation of the development aid in the EU’s externalisation of migration policy”.[5]

Despite the financial incentives, the effects of the EU’s return policy towards Afghans were limited: between 2014 and 2018, on average, only about 4,000 Afghans returned to their country of origin annually. At the same time, the rate of Afghans who did not return was over 25,000 per year (the highest by origin state in the EU, see Fig. 2). The lack of progress on returns prompted the EU to sign another document, the Joint Declaration on Migration Cooperation (JDMC),[6] with Afghanistan in April 2021 to facilitate and accelerate deportations.[7]

Despite the Taliban taking over many regions of the country prior to the foreign forces withdrawal this year, and the growing number of IDPs (and strong criticism from NGOs and human rights organisations), some EU members continued this policy until the fall of the government in Kabul in August. Although on 8 July Afghanistan’s Ministry of Refugees and Repatriation asked the EU to stop returns due to the increasingly difficult situation, on 10 August, six European countries—Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Greece, and the Netherlands—appealed to the Commission not to stop the deportations, as it would send “a bad signal that could encourage even more people to come”.[8]

Deteriorating Security in Afghanistan

The security situation in Afghanistan had been worsening long before the Taliban took over the country this year and had accelerated since the end of the NATO military mission and withdrawal of most international troops in December 2014. The number of enemy attacks almost doubled between 2014 and 2020 (Fig. 3), with the Taliban taking more and more territory. According to the U.S. military, the number of districts under the control or influence of the government in Kabul decreased between 2015 and 2018 by 16% to little more than half of the country (56%). In 2018, the Taliban ruled 12% of districts, and 32% remained contested by both sides. Then, the Pentagon stopped publishing relevant information, so the further increase in Taliban control was not as delineated.

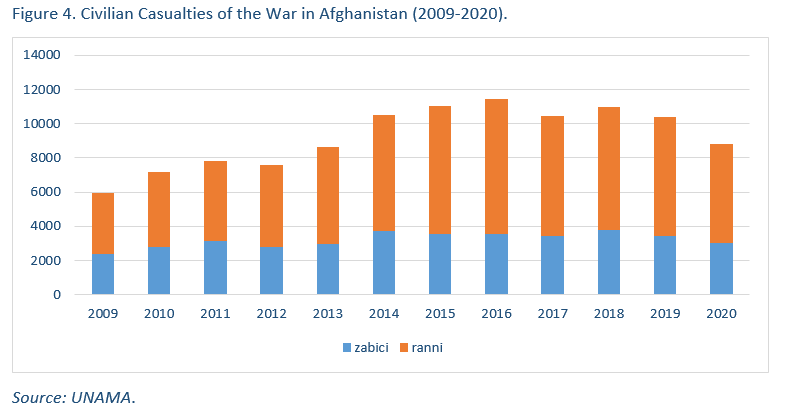

As a result of the intensified fighting, the number of civilian casualties rose significantly from 2009 to 2017, although it decreased slightly in the following years. (Fig. 4). Still, in 2020 more than 3,000 Afghans were killed, mostly related to violence by anti-government forces (62%), but also by pro-government forces (25%).[9] During the first half of 2021, the number of casualties again increased dramatically (47% in comparison to the first half of 2020) as a result of the start of the decisive Taliban offensive. As a result, by just August 2021, more than 550,000 people had fled their homes, bringing the number of Afghan IDPs to 3.5 million.

The exit of the majority of foreign troops and foreign contractors in 2014 also meant a substantial decrease in aid and resources flowing into the country, reducing options for work and income for many Afghans. This had a highly negative effect on the Afghan economy and standard of living of its citizens. GDP growth dropped from 13% in 2012 to 1.2% in 2018, and then turned negative to -2% in 2020. The percentage of Afghans living below the national poverty line increased from 38% in 2011 to 56% in 2016.[10] International development assistance as a share of GDP decreased from 49% in 2009 to 21% in 2019.[11] Yet, the Afghan government continued to run the country, but almost exclusively thanks to financial support from abroad. In 2018, $8.2 billion out of $11 billion in total (so nearly 80%) of government expenditures were financed from international aid.[12] At the international donors conference in Geneva in November 2020, the international community pledged to continue to support Afghanistan with $3.3 billion in civilian aid in 2021 and annual commitments thereafter, which were expected to stay at the same level year-on-year (making it $12 billion between 2021 and 2024).

After the Taliban took control of Kabul on 15 August, they issued assurances regarding amnesty for former government officials and members of the security forces, respect for human rights, including the rights of women, “within the framework of Islamic law”, as well as tolerance and reconciliation with other ethnic and religious minorities. Reports from the field in Afghanistan, however, undermine the credibility of those guarantees. The composition of the temporary government announced on 7 September (and expanded on 22 September) is not at all representative and does not include a fair representation of non-Pashtun groups or different political factions.[13] Recently, news has emerged from Afghanistan about extrajudicial and targeted killings of members of the former system, forced displacement of the population, and persecution of certain minorities. The new authorities have restricted the right to protest, freedom of media, and women’s rights, including blocking girls in grades 9-12 from returning to schools (officially only “a temporary restriction”).

In northeastern Afghanistan, in the Panjshir Valley, the Taliban have not completely defeated the National Resistance Forces (NRF) led by Ahmad Massoud and former Vice President Amrullah Saleh (who has claimed the powers of the presidency), and in other provinces, local resistance fighters have emerged (e.g., in Balkh and Nangarhar). Despite this, there is no real and viable alternative opposition to the Taliban; most members of the former regime have fled abroad or joined the Taliban. The more serious challenge to the new rulers at the moment is enforcement of cohesion and discipline among the different Taliban factions and rank and file in the provinces and different levels of the administration.[14]

The main challenge in the security realm is the growing threat posed by ISIS-K, which has increased the intensity of terrorist attacks, such as the one on a Shia mosque in Kunduz on 15 October, as well as targeted killings. With the internal situation deteriorating, more disenfranchised people may be willing to join ISIS-K. A gradual return to the repressive governance of the Taliban-run first Islamic Emirate in Afghanistan in the 1990s will stir growing opposition among Afghans, leading to destabilisation and the prospect of a new civil war.

At the same time, the country’s economy is collapsing in the wake of the rapid, chaotic transition, the breakdown in the administration, and withholding of international aid. The sudden freeze on government-controlled foreign assets ($9 billion) in American banks and suspension of aid by the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, trust funds, and bilateral donors has caused a liquidity crisis and deepened the economic and humanitarian crises. Further, the change in power in Kabul just adds to the list of grave problems in 2021, including severe drought and floods, COVID-19, and the fighting, all of which contribute to dire conditions in the country. Winter will only make the situation worse. The World Food Programme warns that only 5% of Afghan families has access to enough food and that food insecurity is now affecting those living in urban areas, not only villagers.[15] According to the United Nations Development Programme, Afghanistan faces nearly universal poverty by spring 2022 when 97% of the population is likely to be living below the national poverty line (from 72% currently) .

Surprisingly, the difficult economic and political situation has not yet led to massive emigration from the country. Apart from the chaotic evacuation from Kabul airport witnessed in August, there is no mass exodus to neighbouring countries. According to UNHCR, since the beginning of 2021 until 2 October there were 37,800 refugees from Afghanistan registered in the region, including 21,700 in Iran, 10,800 in Pakistan, and 5,300 in Tajikistan.[16] Though the real number is likely much higher, as most Afghans flee the country through irregular routes and are not recoded by the international organisation, this formal figure is still less than expected. Iran’s own estimates show, for instance, that between 100,000 and 300,000 Afghans in total have reached Iran this year.[17]

The relatively low official numbers of Afghan refugees may be the result of policies by Taliban and neighbouring states. During their final offensive, the Taliban took control of all border crossings with neighbouring countries and closed them. Although they promised to allow Afghans to continue to evacuate after 30 August, they also signalled that they are not interested in the exodus of people important for the economy and administration of the country. In reality, legal travel out of Afghanistan is impossible as passport offices have remained closed for many weeks. The closure of most foreign embassies in Kabul also means that in the country it is impossible to get visas to go to Western countries. While flight connections are resuming gradually, it remains up to the Taliban to decide who can get on each plane.

At the same time, Pakistan and Iran, which combined host more than 2.3 million registered Afghan refugees (1.5 million and 800,000, respectively), have closed their borders and seem less likely to receive new arrivals. Small communities of new refugees are being kept in makeshift camps along Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan. Yet, unlike during the previous wars in Afghanistan, neighbouring countries claim they have no capacity to host a mass migration of Afghans because of their current difficult economic situation and concerns about security. In recent years, both Iran and Pakistan intensified campaigns of returns of Afghans to Afghanistan despite the clearly deteriorating security situation. Between January and September 2021, Iran sent back to Afghanistan 858,000 Afghans—and continuing since the Taliban takeover—with Iran citing the economic crisis at home as a result of U.S. sanctions.[18] Also, Turkey has in the last several years constructed a wall on its border with Iran to defend against any new wave of refugees. Double control of the border by Taliban and neighbouring countries means that opportunities for mass migration out of Afghanistan are largely constrained.

However, the lack of legal pathways for emigration will push the most desperate Afghans to try some irregular path. If the internal situation and economic crisis in Afghanistan deteriorate further, more will start going abroad. Some might seek to get to Iran, Pakistan, and Central Asian republics where they may decide to try for Europe next.

For now, the most likely scenario is the emigration to Europe of Afghans who already reside in third countries. It is worth remembering that the total number of Afghans in Iran is estimated at 4 million people (including 780,000 refugees, 58,000 legal passport holders, and 2.6 million undocumented migrants[19]). Besides Iran and Pakistan, large communities of Afghans live in Turkey (including 124,000 refugees)[20] and Russia (estimates are up to 150,000). The increasingly hostile attitude of the authorities and societies of these countries towards migrants, especially newcomers, may push some of them farther towards Europe.[21]

EU Support for Afghanistan

As the Taliban took power, EU Member States began evacuating their Afghan associates. From the beginning of the fall of the government until the end of August, around 22,000 Afghan citizens were evacuated to 24 EU Member States. Subsequently, EU representatives demanded that the Taliban allow foreigners and Afghans to safely leave the country. In August, the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen indicated several groups of particularly vulnerable people who may count on priority evacuation from Afghanistan to Europe: girls, female journalists, human rights defenders, teachers, judges, lawyers.[22] She also announced financial support from the EU budget for countries willing to help with resettlements.

The issue of Afghan resettlement in the EU was one of the topics of the High Level Forum on Afghanistan convened by High Representative Josep Borrell and Home Affairs Commissioner Ylva Johansson on 7 October.[23] During the meeting, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi said that 85,000 Afghan refugees are likely to be in need of resettlement sites somewhere in the world within the next five years and asked the EU to consider offering half of these places. However, the effectiveness of resettlement to the EU to date has been moderate (in 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, “EU+” countries received only 10,640 people in total, or 58% less than in 2019). In the case of Afghanistan, no specific declarations were made by the Member States. The Council conclusions of 15 September stated only the need to create the possibility of “safe departure of Afghans” to the Member States, which “will decide on their own to admit such people on a voluntary basis”.[24]

With the Taliban assuming full power in Afghanistan, the EU suspended the return policy of Afghans already present on its territory. This was in line with the recommendation issued by UNHCR on 16 August calling for a halt to the forced deportations to Afghanistan of people who had not been granted international protection.[25] Moreover, the UN agency expressed the opinion that “it would be inappropriate to forcibly send Afghan citizens and citizens to other countries in the region” (e.g., Iran, Pakistan) where there is already a large concentration of Afghans. Nevertheless, the preliminary EU Action Plan to deal with the events in Afghanistan, released on 10 September, stated that the situation preventing the deportation of Afghans to their country of origin “will not improve in the foreseeable future”, but allowed readmission to third countries “if the legal requirements are met”.[26]

After the Taliban took over Kabul, the EU suspended its development assistance to Afghanistan, as did the Member States.[27] The EU had been the biggest source of Official Development Assistance (ODA) to that country in recent years, and the European Commission itself was the second-biggest donor after the U.S., distributing some $438 million in aid in 2019. At the donors conference in Geneva in 2020, the Commission pledged support of €1.2 billion in 2021-2024.[28] These funds are now frozen and their release “strictly conditioned on fulfilling political conditions”.[29] At the foreign affairs ministers meeting on 3 September, five benchmarks were agreed towards the Taliban: countering terrorism, respect for human rights, allowing Afghans and foreigners wanting to flee to leave Afghanistan, forming an inclusive and representative government, unrestricted access to humanitarian aid.[30]

The EU’s suspension of support does not include humanitarian aid. On the contrary, in August President von der Leyen pledged an increase in humanitarian assistance from the €50 million planned for 2021 to €200 million.[31] In her State of the Union Speech on 15 September, she announced that the EU will give an additional €100 million to a total of €300 million. During the G20 meeting on Afghanistan on 12 October, the EU promised an aid package of almost €1 billion. This includes the €300 million previously promised, along with €250 million for basic services within the formula of “humanitarian aid plus” and close to a half billion euro for the region.[32] Funds for Afghanistan’s neighbours are meant to help them create the conditions and ease the burden to host Afghan refugees closer to their homes. The package also aims at providing funding for safe channels of migration to the EU for Afghans and the creation of conditions for the reception and integration of people in the region. Third countries, whether regional or transit, are becoming key partners of the EU in steering and controlling the irregular migration of Afghans to Europe. The EU promises close cooperation with these partners in order to strengthen their “resilience to provide shelter [and] decent and secure conditions for living”.[33]

Migration from Afghanistan and EU Asylum Policy

The EU is not prepared for an increase in migration from Afghanistan, not least because of the deadlock in reform of the EU’s asylum system inaugurated after the 2015-2016 crisis. The latest proposal on this matter presented by the Commission in September 2020 was not well-received by the Member States, which viewed it as insignificant progress in negotiating the package.[34]

The large differences in the Member State asylum systems, which are reflected in the level of recognition of Afghan asylum applications, are a rationale for the proposed introduction of extra-border pre-screening and for strengthening the monitoring of national systems to ensure consistency. Moreover, the migration pressure (including Afghans) on the eastern route to Europe, which is increasing this year, as seen in Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland (which are also the countries traditionally sceptical about solidarity mechanisms proposed by the European Commission), could be a factor facilitating agreement on this part of the package.

However, the forced migration by Belarus on the eastern border of the EU obscures the humanitarian dimension of the phenomenon. This limits the EU’s reaction to using the tools of diplomatic and financial pressure on the Belarusian authorities and to countering irregular migration. In her State of the Union, EC President von der Leyen announced changes to the Schengen Border Code to strengthen the protection of the external borders. In response to this announcement, 12 Member State interior ministers called on the Commission to formulate clear rules under the reform regarding actions to be taken in the face of a hybrid attack at the borders. They also indicated that the EU should finance the creation of physical barriers at the external borders from a common budget.[3

The low and deteriorating efficiency of the EU return policy in recent years also poses a challenge to a compromise on the asylum package. The EC proposal gives the Member States a choice of relocation, financing, and/or organisation of migrant returns. According to the European Court of Auditors, despite stronger financial and institutional support, as well as increased EU diplomatic efforts, the effectiveness of the return policy as measured in returns to total migrants with “return decisions” has decreased from around 40% in 2016 to 29% in 2019 (and to only 19% for third-country nationals from outside Europe). As indicated above, it has been the least effective so far in relation to Afghans, and the growing instability of their country does not allow continuation. In this context, it is therefore difficult to treat returns as an alternative to relocation.

Conclusions

The Taliban takeover of Afghanistan has changed the goals of the EU’s migration policy towards Afghans. A new priority has emerged, which is to continue the controlled evacuation of Afghans who cooperated with European countries in the past. The second goal of protecting the EU’s borders and controlling and reducing irregular migration to Europe from Afghanistan itself and from third countries has been strengthened. Under the current conditions, the EU must give up another priority—the deportation of Afghans to their homeland.

The implementation of the first task will depend on intra-EU arrangements, talks with the Taliban, and the preparation of a system enabling legal travel to Europe, both from Afghanistan and through third countries. The resettlement of selected people to the EU will require the will of the Member States to accept the refugees.

The achievement of the second goal will be a derivative of Taliban policy and the development of the internal (political and economic) situation, as well as the EU’s relations with third countries, mainly Afghanistan’s neighbours. A boost in humanitarian aid is seen now as a major tool to counteract an emerging migration crisis.

Thus, development aid is becoming the main instrument for implementing the EU’s migration interests, both in Afghanistan and in third countries. Additional funding to cover the costs of hosting refugees is expected to help persuade Afghanistan’s neighbours to open borders to fleeing Afghans and to cooperate more on migration control. However, the countries of the region may expect additional economic or political benefits in return for such cooperation, which exposes the EU to a kind of blackmail. In addition to increasing financial assistance some countries, for example, Iran, can expect EU support for lifting international sanctions that worsen the country’s economic situation. In other cases, there may be other options, such as with Pakistan, which seeks an extension of trade preferences with the EU under the GSP+ system, or with Turkey on implementation of visa facilitation.

While mass migration from Afghanistan to Europe is currently unlikely, the situation may change rapidly, especially if the internal situation, particularly the economy and security, deteriorate quickly over the winter. For the moment, however, the more serious problem for the EU may be increased migration pressure from Afghans already outside their homeland. In addition to an influx of additional asylum applications from Afghans already residing in the EU, more migration from the multi-million Afghan diaspora in Asia can be expected. The difficult internal situation in Afghanistan and the reluctance to accept refugees in neighbouring countries will prevent deportations of Afghans. Moreover, Europe coordinating evacuations from Afghanistan while deporting asylum seekers back to the country would undermine the international refugee regime and jeopardise the EU’s global credibility. The situation of the Afghans may therefore lead to political problems in European countries and new tensions in the field of asylum policy, return policy, or the qualification of “safe third countries”.

Solving the current crisis requires tackling the root causes of migration in Afghanistan, which goes well beyond humanitarian aid and requires making difficult political decisions. One of this is whether to establish meaningful cooperation with the Taliban. The restoration of promised development aid would play a key role in stabilising Afghanistan’s economy. Without a resumption of full financial support, the economic and political situation will worsen, leading to a severe humanitarian and refugee crisis. It is therefore in the EU’s interests to be pragmatic about the conditions for resuming aid and to find a way to channel bilateral aid and support the mobilisation of major trust funds supported by international organisations. This is all the more important since EU members were involved in the NATO mission in Afghanistan and therefore may be accused of being responsible for the current humanitarian and political crisis.

The publication is prepared in the framework of initiative: Migration and Development: Sharing knowledge between Poland and Norway (MiDeShare). The Initiative is funded by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through the EEA Grants and Norway Grants.

Working together for a green, competitive and inclusive Europe.

[1] Persons as the subject of asylum applications pending at the end of the month by citizenship, age, and sex—monthly data (rounded) (online data code: MIGR_ASYPENCTZM ). Source: Eurostat.

[2] European Commission, “Joint Commission-EEAS non-paper on enhancing cooperation on migration, mobility and readmission with Afghanistan,” Brussels, 2 March 2016.

[3] S. E. Rasmussen, “EU's secret ultimatum to Afghanistan: accept 80,000 deportees or lose aid,” The Guardian, 28 September 2016.

[4] M. Quie, H. Hakimi, “The EU and the Politics of Migration Management in Afghanistan, How can coordination be improved to address competing policy priorities and migration pressures?”, research paper, Chatham House, 13 November 2020, p. 4.

[5] M. R. Atal, “The Asymmetrical EU-Afghanistan Cooperation on Migration”, The Diplomat, 12 May 2021.

[6] Joint Declaration on Migration Cooperation between Afghanistan and the EU (JDMC), European Commission, Brussels, 13 January 2021.

[7] “The JDMC: Deporting People To The World’s Least Peaceful Country”, ECRE Policy Note #35, European Council on Refugees and Exiles, 2021

[8] “Six countries urge EU to continue Afghan deportations,” Deutsche Welle, 10 August 2021.

[9] “Afghanistan Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict Annual Report 2020,” UNAMA, Kabul, Afghanistan, February 2021, p. 17.

[10] World Bank Development Indicators, “GDP growth (annual %) – Afghanistan” and “Poverty headcount ratio below national poverty line (%) – Afghanistan,” https://data.worldbank.org (accessed 13.10.2021).

[11] World Bank Development Indicators, “Net ODA received (% of GNI) – Afghanistan,” https://data.worldbank.org (accessed 13.10.2021).

[12] T. Haque, N. Roberts, “Afghanistan’s Aid Requirements: How much aid is required to maintain a stable state?”, Expert note hosted by the Overseas Development Institute (UK) Lessons for Peace project, 10/2020, p. 4.

[13] I. Bahiss, “Afghanistan’s Taliban Expand Their Interim Government,” International Crisis Group, 28 September 2021.

[14] PISM, Confereence: “Thomas Rutting na konferencji Afghanistan, Taliban and Migration” 7 October 2021.

[15] WFP, “In the grip of hunger: only 5 percent of Afghan families have enough to eat,” 23 September 2021.

[16] UNHCR, “Reported newly arrived Afghans in need of international protection to neighbouring countries since 1 January 2021,” https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/afghanistan#_ga=2.164591551.1436408364.1633444753-1548293199.1630422186 (accessed 05.10.2021).

[17] Conversations with UN officials, Iranian experts in Tehran, 06-07 November 2021.

[18] IOM, “Return of Undocumented Afghans,” Weekly Situation Report, 03-09 September 2021.

[19] UNHCR, “Iran at glance,” Tehran, October 2021.

[20] UNHCR, “Turkey Fact Sheet,” September 2021. This number includes only registered refugees. The total estimates of Afghans living in Turkey by UNHCR are close to 300,000.

[21] S. Sanderson, “Turkey turns against migrants as fears of Afghan refugee crisis grow,” Info-migrants, 7 September 2021.

[22] European Commission, “Statement by President von der Leyen at the joint press conference with President Michel following the G7 leaders’ meeting on Afghanistan via videoconference,” STATEMENT/21/4381, Brussels, 24 August 2021.

[23] The forum was attended by the ministers of foreign affairs and ministers of internal affairs of the EU Member States, as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, representatives of the European Parliament, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and the Director General of the International Organisation for Migration.

[24] Council of the European Union, Council conclusions on Afghanistan, Brussels, 15 September 2021.

[25] UNHCR, “UNHCR Position on Returns to Afghanistan,” August 2021.

[26] “NOTE from: Commission Services to: Delegations: Operationalisation of the Pact – Action plans for strengthening comprehensive migration partnerships with priority countries of origin and transit - Draft Action Plan responding to the events in Afghanistan” (Council doc. 10472/1/21 REV 1, LIMITE), 10 September 2021.

[27] “EU suspends development aid to Afghanistan, must enter dialogue with Taliban, Borrell says,” Euronews, 18 August 2021.

[28] European Commission, “EU reconfirms support for Afghanistan at 2020 Geneva Conference,” Press release, 24 November 2020.

[29] European Commission, “Statement by President von der Leyen …,” op. cit.

[30] EEAS, “Afghanistan: Press statement by High Representative Josep Borrell at the informal meeting of Foreign Affairs Ministers (Gymnich), Brdo pri Kranju, Slovenia,” 03 September 2021.

[31] European Commission, “Statement by President von der Leyen …,” op. cit.

[32] European Commission, “Afghanistan: Commission announces €1 billion Afghan support package,” Press release, Brussels, 12 October 2021.

[33] “NOTE from: Commission Services to: Delegations …,” op. cit.

[34] J. Szymańska, “New Pact on Migration and Asylum: Linking Asylum with Returns,” PISM Spotlight, No 70/2020, 25 September 2020.

[35] N. Nielsen, “Dozen ministers want EU to finance border walls,” EU Observer, 8 October 2021.