The Upcoming Scottish Parliamentary Elections and the Challenges of Brexit and the Pandemic

Scotland’s Status

The country is distinguished as part of the United Kingdom by its historic statehood and the treaty union with England (1706-1707) granting Scotland legal, religious, and educational autonomy within the union. While Scotland’s demographic and economic potential is only around 8% of the UK’s, it is equivalent to the Welsh and Northern Irish combined. The contemporary national movement has been pro-independence. The increase in its popularity resulted in attempts to introduce devolution (decentralisation) since the 1970s, and which materialised in 1998.

The Scottish devolution is based on a national government and parliament with legislative powers. Competences other than those reserved to the UK authorities were transferred to the national level (e.g., education, health, internal affairs policy). The reserved powers concentrate on foreign, security, monetary, trade policies, and the functioning of the UK (e.g., holding an independence referendum). The Scottish authorities’ freedom of action has been limited by the lack of control over monetary and, in part, fiscal policies. Most of the national public expenditure is financed through UK government grants, which allow a subsidy of about 20% at the expense of the wealthiest regions in England (the Barnett formula).

Autonomous Political System

This has enabled the SNP to compete effectively for power with Labour. Despite the nationalists’ defeat (45% to 55% of votes), the 2014 referendum established independence as the most important political cleavage in Scotland and consolidated separatist voters around the SNP. This resulted in the party’s electoral hegemony and its victories in all subsequent elections. In reference to independence, the SNP is supported by the Scottish Greens. The SNP’s electoral base is in the Central Belt between Edinburgh and Glasgow where most of the country’s population lives. The party’s rule since 2007 has resulted in internal centralisation of Scotland, provoking intra-Scottish autonomous movements in turn. For example, last year Shetlanders initiated efforts to separate from Scotland as a British Crown dependency (the Isle of Man model). Due to the breakdown in support for Labour and the Liberal Democrats since 2015, the unionist leadership was taken over by the Tories.

Brexit

Support for the UK’s EU membership in the 2016 referendum by the majority of Scottish voters (62% to 38% of votes) has enabled the SNP government to call for another independence referendum. Although support for the EU does not equal independence, the European question divides the unionists much more than the separatists. The UK’s Brexit policy, created mostly unilaterally by the central authorities, has been severely criticised by the SNP government. They called for Scotland to remain in the customs union and the EU single market, which would have resulted in a customs and regulatory border within the UK (as in the Northern Ireland case). Consequently, first the SNP government and then the party’s MPs in the House of Commons voted to reject the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA).

Scotland’s economy is closely linked to the rest of the UK (65% of its trade is with the rest of the UK and 18% with the EU). However, due to demographic reasons and intra-UK migration, Scotland remains open to EU immigration. EU structural, agricultural, and research funds were important to the national economy, especially for sectors underfinanced by the UK. The narrow scope of the EU-UK agreement dissatisfied many people in Scotland. It has also been negatively assessed by local fishermen, whose interests Johnson was to defend.

The SNP government wanted to automatically take over the competences regarding devolved policies repatriated from the EU. However, the UK Internal Market Act (UKIMA 2020) established uniform rules for UK market access and competition policy, strengthening the British economy and the position of the UK government in negotiations with third countries. SNP was also opposed to the act’s provisions enabling the UK authorities to finance in Scotland economic investments (e.g., infrastructure) and cultural projects (e.g., sports events) aimed at integrating the UK market.

The Pandemic’s Impact

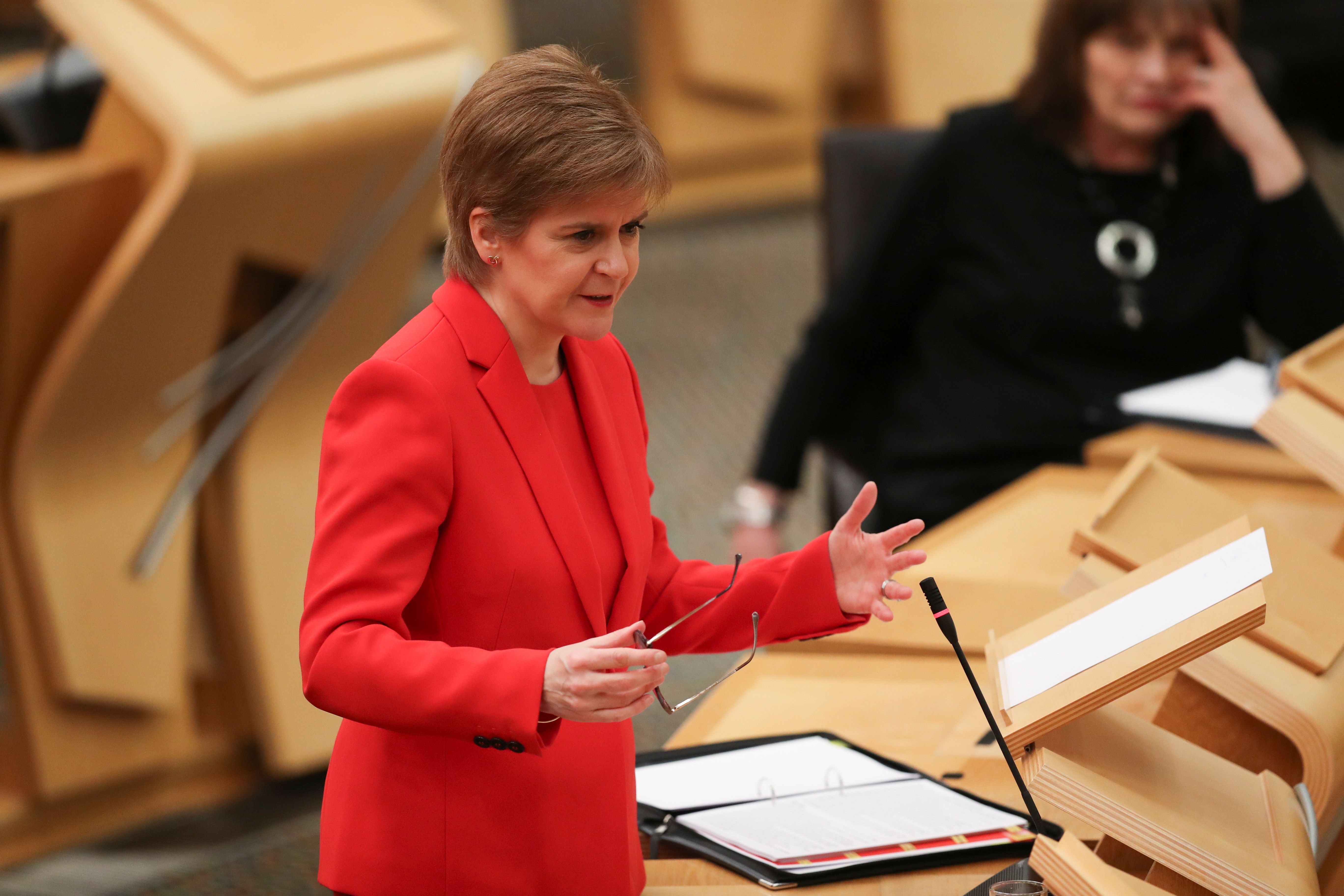

Scotland’s policy to combat COVID-19 has consistently been based on relatively strict social distancing implemented at the earliest possible stage. The high support for the SNP government seems to result not so much from the lack of defeats as from efficient communication. For example, Johnson has often changed the levels of restrictions in England, in many cases with minimal notice. Meanwhile, the Sturgeon government has been maintaining a protracted lockdown and has kept defending it in daily press conferences. In proportion to the population, the number of infections in Scotland is 40% lower than the UK average and the second wave of the pandemic was relatively mild. However, organisational errors in the care of seniors have resulted in Scots being overrepresented among Britons who died from COVID-19 (8.4%), while the country’s vaccination rate is 40% lower than in England.

In addition, the pandemic has highlighted the structural problems of SNP policies implemented since 2007, such as the relocation of medical and other services from distant parts of the country to the Central Belt. Moreover, problems with distance learning have exposed the systematic deterioration of education (e.g., PISA rankings). Finally, the SNP’s pandemic policy has been overly restrictive from the perspective of sparsely populated regions and strengthened intra-Scottish separatisms.

Mass vaccinations launched last December are key to Johnson’s rebuilding of the UK’s image in Scotland. The efficiency of UK institutions in registering two vaccines, financing development of one of them (Oxford-AstraZeneca), and their distribution in England and to central warehouses in other parts of the UK has particularly been emphasised, as has the financing of economic relief from low-interest UK public debt, which would not be accessible to independent Scotland.

Perspectives

The Scottish parliamentary election scheduled for 6 May will be a plebiscite on the politics of Brexit, pandemic, and independence. The declared support for the parties has been stable since early 2020. At present, they poll as follows: SNP, around 50%; Tories, 20%; Labour, 15%; and the Greens, 12%. Consequently, a nationalist majority is very likely.

The SNP’s and Greens’ main election goal is to confirm public support for the roadmap to independence announced on 24 January. If they win the referendum, both parties want Scotland’s re-accession to the EU. The split unionist camp (Tories, Labour, Liberal Democrats) is deprived of effective leadership due to the resignation of Conservative Ruth Davidson in August 2019 in response to Johnson’s Tory leadership. The most important challenge to the SNP’s domination is the infighting between the Sturgeon faction and her predecessor, Alex Salmond. While grounded in reciprocal allegations of abuse of power, the struggle will affect the referendum timing (after or during the pandemic) and constitutional strategy (with or without the UK government’s consent and conditions, as in Catalonia).

From the EU’s short- and medium-term perspective, the TCA will help preserve the current economic exchange with Scotland, under the caveat of significant increase in transaction and transportation costs. While the free movement of people expired on 31 December, it is likely that EU citizens wishing to work in Scotland will obtain visas relatively easily.

In the long run, separatism will be a key challenge for both the British authorities and the EU. It has already provoked heated debates in the UK. For example, the Johnson government has been considering how to use the repatriated competences to empower the Shetland and Orkney regional authorities over the Scottish ones. The disarmament and neutrality aims, strongly supported in the ranks of the SNP and the Greens, would significantly impact the security of Poland and other European NATO countries. This is due to the possibility of the UK losing its critical infrastructure located in Scotland. Importantly, there are no UK alternatives for relocating infrastructure from the Clyde, servicing the UK nuclear submarine fleet, without losing some capabilities, while air bases at Lossiemouth and Leuchars are key to controlling Russian activities in the North Atlantic.