State of the EU-India Trade and Investment Negotiations

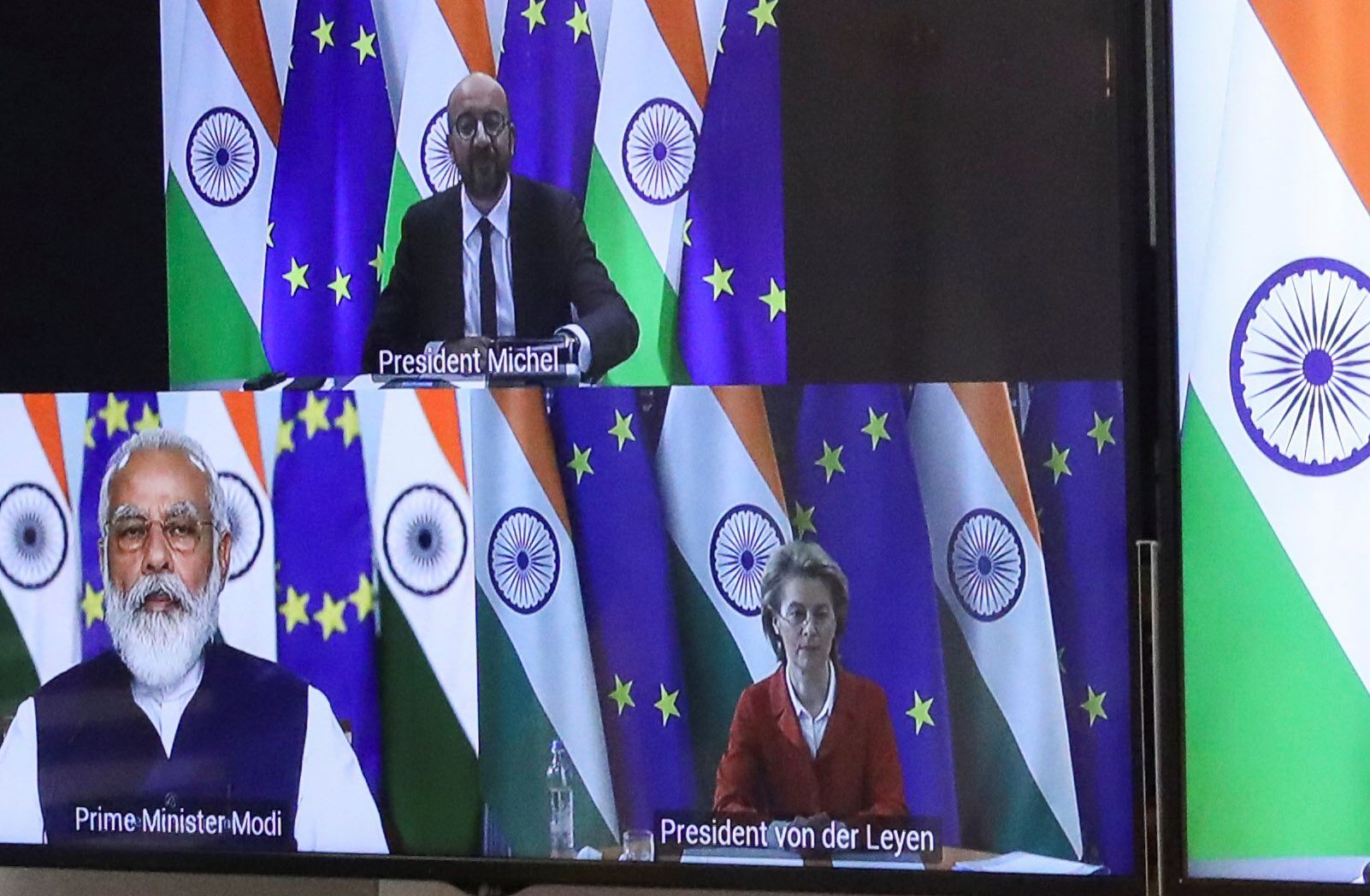

The negotiations of the EU-India Broad-based Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA) started in 2007 but stalled in 2013 over several important disagreements and the level of ambitions regarding, for example, sustainable development. Yet, since 2077 there has been a renewed interest in reopening the negotiations along with an improved atmosphere and regained momentum in bilateral ties, best illustrated at the EU-India Summit on 15 July 2020. Though the parties did not restart the BTIA negotiations, they proposed to establish a regular High Level Dialogue at the ministerial level “to provide guidance to the bilateral trade and investment relations”.

In autumn 2020, Indian and EU officials started pointing towards two separate deals—one on trade and a second on investments—as the most likely option going forward. The first High Level Dialogue on trade took place on 5 February this year when both sides “reiterated their interest in resuming negotiations” of trade and investment agreements. Indian media reported that some mini trade deal was likely to be concluded at the forthcoming India-EU Leaders Meeting planned for 8 May. This, however, is debatable as EEAS officials informed in March that the EU is still looking for a comprehensive and ambitious agreement. It seems that a stand-alone investment agreement would be an easier task, but many things still need to be sorted out before a breakthrough can be announced. Hence, to understand what outcome is possible, a closer look at India’s position on the deal between the EU and China is revealing.

India’s Reactions to the CAI

| The Indian reactions to the CAI must be assessed in the context of the severe deterioration in India's ties with China. |

EU-China relations have been followed with growing attention in India in recent years. Hardening of the EU’s position towards China since 2019 when the European Commission (EC) called it a “systemic rival” and the Union’s stances visible especially during the COVID-19 pandemic were received positively by India. The sudden conclusion of the CAI negotiations then came as an unpleasant shock. The Indian reactions must be assessed in the context of the severe deterioration in India’s ties with China. Following the border crisis in Ladakh in June 2020, India’s Minister of External Affairs characterised India-China relations as being in the “most serious situation since 1962” when the countries fought a war.

The CAI has not been commented publicly by Indian officials. Yet, it attracted some attention and provoked criticism in Indian think tanks, generally following three main arguments.

In the first argument, the EU was seen as stepping back from its hard position on China. It was perceived as a show of “naivete by the EC”, delivering an “unambiguous political victory for Beijing”. The CAI was criticised as a “bilateral deal with an authoritarian power that seems to have a very different understanding of multilateralism” and to which the EU “not only turns a blind eye, but actually rewards its increasingly aggressive behaviour”.

The second was that by concluding the negotiations the EU undermined its normative power. Indian observers saw the CAI as a “sell-out of Europe’s core values” and an act that “glosses over the Chinese Communist Party’s [CCP] human rights abuses in China” and which “marks the move of the Union from ‘values’ to ‘valuations’ and from ideals to trade”.

The third sees Indian commentators worried about the state of EU-U.S. relations and envisioning serious limitations of a wider coalition of Western democratic states that could jointly stand up to China. While the Biden administration in the U.S. has signalled the willingness to move away from Trump’s unilateralism on China, “Brussels has opted for its own form of unilateralism”, and by acting with “regrettable timing”, has “broken ranks with other democracies” and provided China a diplomatic victory.

The more obscure reason for the Indian criticism was that the CAI weakens India's position in the trade and investment negiotiations with the EU. |

While the Indian reactions to the CAI are fully understandable in the context of India’s strained relations with China, what was largely absent in most of the commentary was the agreement’s negative impact on Indian economic interests. In that regard, the less-acknowledged reason for the Indian criticism was that the CAI weakens India’s position in trade and investments negotiations with the EU.

The CAI in the Context of the Indian Trade and Investment Policy

Though many experts question the real economic benefits of the CAI, it must be noted, however, that the EU received some commitments from China that India has traditionally been reluctant to offer. Thus, the CAI could have some important repercussions for EU-India economic relations in several dimensions.

Sustainable Development. As EU chief negotiator Maria Martin-Prat said at an event organised by the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM), the chapter on sustainable development was the hardest to negotiate. Though China’s commitments are rather general and vague, India has been traditionally hesitant to include any non-trade matters in economic agreements. Hence, disagreements over sustainability clauses, including labour rights and climate, were among the main reasons for the impasse in negotiations on the BTIA. China, by giving even loose commitments on working to ratify International Labour Organisation (ILO) conventions or on climate-change issues, makes India’s position much harder to maintain vis-à-vis the EU.

- Market Access. The CAI is believed to make some minor improvements in market access in China in such sectors as financial and health services or electric vehicles. India appears to offer a more open market in general for European FDI than China on many accounts. There has been significant progress in the liberalisation of FDI policies under Prime Minister Narendra Modi and an expansion of the list of sectors allowing for 100% foreign ownership under the automatic route, when the government’s consent is not needed, such as in manufacturing, railways, or healthcare. However, there are still some areas where FDI is prohibited (i.e., real estate, e-commerce) and where prior approval is required through the government route (e.g., defence industry). There are also several sectors with certain foreign caps on FDI (i.e., the automatic route up to 48% in the pension sector or the government route beyond 49% in telecom services). India, like China, limits the access of foreign companies to public procurements, expects investors to work through joint ventures with local partners, and implements technology-transfer requirements on FDI in specific sectors (i.e., defence). Moreover, the “Self-Reliant India” campaign (Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan), launched in May 2020 and aimed at increasing India’s economic self-sufficiency (similar to China’s “dual circulation strategy”), has raised concerns of more protectionism. Foreign diplomats complained that “growing restrictionson market access […] and new limitations on the free flow of data” may become a barrier to more investments. Therefore, the CAI may put extra pressure on the Indian government to further improve market access for foreign companies. Interestingly, it may be noted that only in February 2021—after the conclusion of the talks on the CAI—the Indian government raised the cap for investments in the insurance sector (to 74% from 49%), signalling its willingness to be more attractive than China .

|

Though the CAI offers only an incoherent state-to-state mechanism of dispute settlement, India does not offer even this kind of protection to new EU investments. |

- Dispute Settlement Mechanism. The CAI lacks investment protection provisions and offers only an incoherent state-to-state mechanism of dispute settlement. India has not been ready to offer even this kind of protection to EU companies. Since the introduction of its new model Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) in 2016, on which new deals are to be based, India has cancelled around 80 BITs (including with all EU Member States). Its model BIT is regarded as “protectionist in scope”, “vague, flawed”, and offering “little succour for Indian or foreign investors”. For instance, it mandates a foreign company to exhaust domestic dispute mechanisms for five years before it can initiate the international investment arbitration procedure. Thus far, only four countries have agreed to sign a BIT with India based on its 2016 model (Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Taiwan, and Brazil). As the CAI offers at least minimal protection, it weakens the possibility that the EU will sign a deal with India based on the latter’s model BIT.

- EU-China Decoupling. To many observers, the CAI was a sign that the EU is against decoupling from China. This is bad news for India, which had hoped to attract more FDI from the EU as it is withdrawn from China. It even started its own decoupling through withdrawal from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in November 2019, implementing a ban on investments from China in April 2020 and on Chinese mobile applications last year. So, the fear is that the CAI could further aggravate the imbalance in the EU’s trade and investment relations with India and China. EU trade with the latter is already seven times bigger than with India ($560 billion and $77 billion in 2019, respectively). More worryingly, while EU-India trade in goods decreased in 2020 (exports from the EU dropped by 2.7%, imports by 8.8%), with China it increased (EU exports rose by 2.2%, imports by 5.6%), making it the EU’s top commercial partner. EU FDI stock in India (€68 billion in 2018) is also less than half that in China (€175 billion). The CAI may further undermine Modi’s plans to turn India into a major manufacturing hub, promoted through the “Make in India” campaign since 2014 and reincarnated as “Self-Reliant India” in 2020.

- India’s Economic Policy. The CAI is another example of an economic pact covering multiple countries signed in the world in recent years, along with the RCEP and CPTPP. This trend goes against the traditional stance of Modi’s government on multilateral economic cooperation. There are worries that “India will be the only country to be left out of all such trade and economic blocs or groupings”. In this regard, the CAI might have been the last straw in pushing the government to rethink its own position in this area by showing that staying outside plurilateral arrangements may mean going out of business.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The finalisation of negotiations on the CAI have done some damage to EU-India political relations and undermined India’s trust in the EU as a like-minded partner when it comes to dealing with China. Yet, political ties will remain strong as ratification of the CAI seems less likely after the exchange of sanctions between the EU and China in March and there is a strong willingness in both Europe and India to regain momentum in cooperation. While the CAI’s impact on EU-India economic cooperation seems negative at first glance, it may bring more benefits in the longer term. The Indian reactions allow a look at the deal from a different perspective, allowing for some interesting observations from the points of view of the EU, India, and the prospects of the EU-India negotiations.

| Contrary to the dominant view in Europe, the Indian reactions suggest that the EU's achievements in concluding the CAI are not insignificant. |

First, contrary to the dominant view in Europe, the Indian reactions suggest that the EU’s achievements in concluding the CAI are not insignificant. It appears to have strengthened the EU’s position and given it certain leverage in negotiating the next deals with other major developing countries like India. China declared concessions that no other large, emerging economy has in the past. It seems that the CAI sets a minimum level of expectations that must be met by the EU’s other partners. The Union should use this leverage now and push harder for sustainability clauses and market access in its negotiations with India.

Second, the CAI seems to be read by India as encouragement to rethink its own trade and investment policy in general, and negotiations with the EU in particular. In a world where economics often trump politics, Indian leaders must find ways to address the growing concerns about their protectionist tendencies. As one Indian author concluded, “instead of finding faults with European behaviour, India should make its economy attractive to outsiders, including Europeans”. That requires serious intent of signing an FTA, and changing its position on the model BIT and sustainability clauses.

Third, the CAI should persuade both European and Indian leaders to work more vigorously towards EU-India trade and investment agreements. European business is keen to diversify its supply chains and invest in new promising markets. India as a like-minded democracy and the only country of comparable market size and production capacities as China that can offer such economies of scale, would be a preferred destination. Not surprisingly, just after the conclusion of the CAI talks, German Chancellor Angela Merkel reached out to Modi to explain the nature of the deal with China and press for the BTIA with India.

| A separate EU-India investment deal seems to be the most likely option, and this could help build the momentum for the resumption of negotiations of a comprehensive economic deal.

|

To attract European investments, India must create more business-friendly conditions and offer at least similar commitments as China. The EU can use the CAI to extract more concessions from India; however, India may use the precedence in the CAI to seek similar vague and not very ambitious commitments in a deal with the EU. As a result, at minimum a separate EU-India investment deal seems to be within reach. This could help build the momentum for the resumption of negotiations of a comprehensive economic deal. The speed-up in economic contacts, including the High Level Dialogue in February and resumption of the EU-India Human Rights Dialogue in April suggest that a breakthrough in EU-India talks is more likely.

For Poland, which supports ambitious EU-India trade and investment deals, the prospect of a quick resumption of the talks is good. The state could support work towards the swift finalisation of negotiations on an investment agreement as well as work on an FTA, which would give more market access and strengthen safeguards for Polish enterprises in India.