More than Mass Testing: Slovakia and the Fall Wave of COVID-19

Compared to the spring wave of the pandemic when Slovakia had the lowest COVID-19 infection and death rates in the EU for several weeks, the rates in the fall clearly worsened. Since the beginning of the pandemic, more than 168,000 coronavirus infections have been detected in Slovakia, with 1,800 people died as a result of the disease. More than 90% of those infections have been detected since the beginning of October. Between 14 and 28 December, Slovakia registered 635 infections per 100,000 residents and 10.2 deaths per 100,000 residents. That placed Slovakia 9th in the EU in terms of the percentage of cases in the population and 15th in by deaths.

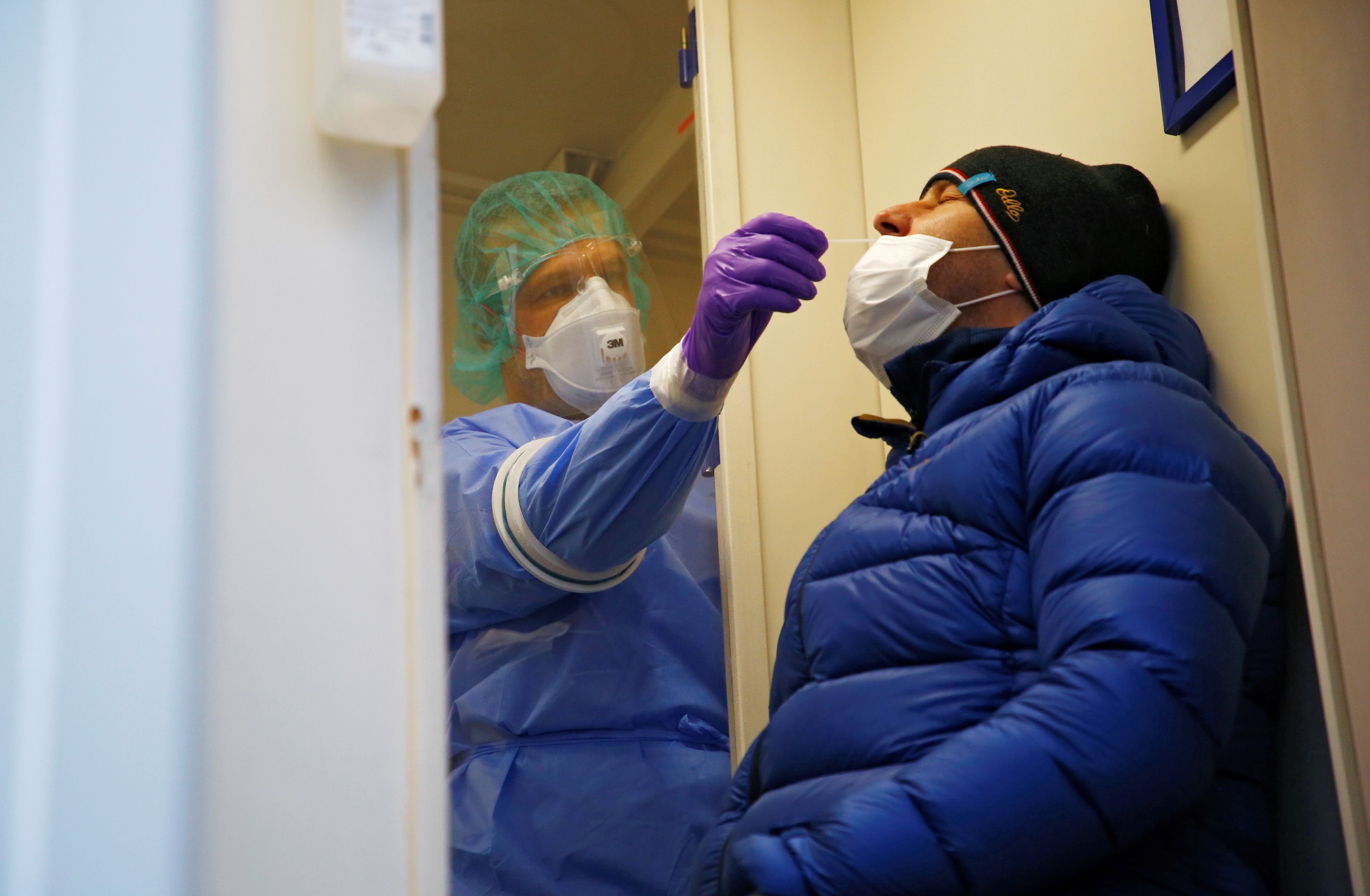

Concept and Results of Mass Testing

Slovakia’s testing for COVID-19 was the largest logistic operation in the country’s history and was made possible by help from the military, volunteers, and others. Slovakia suffers from a deficit of medical staff, so the burden was widened. The pilot phase of the tests was carried out in selected regions where the highest increases in infections were noted. During two rounds—31 October-1 November and 6-8 November—nearly the entire population over the age of 10 was administered an antigen test for COVID-19. In Slovakia, which has a population of less than 5.5 million, about 5.6 million tests were performed, as some people were tested twice. Such high mobilisation was achieved because testing was compulsory—people who refused them were obliged to enter into quarantine—and also because a negative test conferred real benefits, such as more convenient access to stores or an exemption from the ban on leaving the house at night.

The third round of mass testing in December was intended to prove the earlier results. Unlike the previous periods, this time it was voluntary, hence many fewer participants—only about 15% of the population. In turn, by the end of the month, companies with more than 500 employees should start regular COVID-19 testing. According to the Ministry of Health, testing will facilitate social contact in the period before vaccination of the population.

The prime minister explained that all stages of the mass testing were assumed to enable more effective, comprehensive examination of Slovakia’s population and, consequently, to avoid tightening the restrictions. However, in enacting further restrictions, though, Matovič admitted to the failure of the mass testing policy as an alternative to tightening the sanitary regime. The action contributed, though, did help determine who was infected, get them into isolation, and reduced the spread of the pandemic. It was not possible to fully validate the results during the voluntary round of testing given the low participation. The public’s attitude may result from the prevalence of conspiracy theories, especially online. According to a study by GLOBSEC published in December this year, 39% of Slovaks say they believe that the coronavirus does not exist—the highest percentage among the countries of the Visegrad Group.

In the political aspect, testing, according to Matovič, was to demonstrate the effectiveness of the state, strengthen citizens’ trust in institutions and, consequently, contribute to the increase of support for his party, Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OĽaNO). These goals have not been achieved. A poll by the AKO institute published on 21 December indicates a further decline in support for OĽaNO to 14.2%, compared to 25% in the parliamentary elections in February. This would mean if elections were held now it would lose not only to the opposition party, the Voice–Social Democracy, of former Prime Minister Peter Pellegrini (22.8%), founded last summer, but also to the coalition party Freedom and Solidarity (SaS), which has about 16.2% support in the poll (compared to 6.2% in the recent elections).

Other Forms of Fighting the Pandemic

To facilitate the management of the crisis, a state of emergency was reinstated in Slovakia on 1 October, deemed necessary to introduce the many restrictions. It also simplifies procedures for purchasing medical equipment, enables the mobilisation of medical students to work in hospitals, and changes the rules for deploying medical personnel. In summer, Slovakia, unlike Czechia, maintained the obligation to cover the mouth and nose in confined spaces, including on public transport. In view of the worsening infection rates in the country, the Matovič government re-introduced some restrictions, for example, from 7 December strict conditions for crossing the state border apply. The internal movement of people was also restricted—from 19 December it is forbidden to leave the house, except in exceptional circumstances.

The government allows entry to Slovakia without the need for quarantine in the case of a valid negative coronavirus test. The authorities also aim to obtain recognition of antigen tests in other EU countries, which would enable more efficient movement of EU citizens under a more stringent sanitary regime. This mutual recognition was first consulted within the Slavkov Triangle with Czechia and Austria, which also carried out extensive testing. Although Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz cites the Slovak experience, in Austria, participation in mass antigen tests was voluntary: between 4 and 15 December, around 25% of the population was screened.

Dispute over the Restrictions

Despite the slowdown in the infection rate this summer, Slovakia maintained a relatively restrictive sanitary regime. This aroused opposition, among others, from the SaS coalition. Its leader, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Economy Richard Sulík, criticized, among others, the increased restrictions on hotels and ski resorts as the fall wave worsened. In turn, Prime Minister Matovič criticised Sulík for a lack of COVID-19 tests after the first rounds of mass testing and called on him to resign. The inconsistencies in crisis-management also drew criticism from, among others, President Zuzana Čaputová, who called for a more transparent implementation plan for the restrictions. Earlier, she had suggested to the government that the mass testing be voluntary.

To limit increased intra-coalition friction, the Chief Hygienist (appointed and dismissed at the request of the Minister of Health) decides how to manage the restrictions. The legitimacy of the removal of broad restrictions depends on the number of infections and dynamics. On 21 December, Slovakia recorded 1,219 new infections, but four days later, set a record of 4,046.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The case of Slovakia shows that mass testing for COVID-19 should not be seen as an alternative to tightening restrictions. However, it played a role in limiting the spread of the pandemic, especially in regions with high infection rates. Mass testing has further highlighted the friction between the president and the head of government, and even more clearly, the animosities within the government coalition. The deepening conflict between Matovič and Sulík has a negative impact on the effectiveness of the state’s crisis-management. If it continues to build, it cannot be ruled out that the government coalition will collapse.

Foreign activities regarding the use of coronavirus tests confirm the increasing use of regional cooperation by the Matovič government through the Slavkov Triangle. After managing the border regime during the spring wave, this forum proved practical from the Slovak perspective in counteracting the effects of the pandemic. To better coordinate regional activities in this area, the states of the Slavkov Triangle, as well as Hungary and Slovenia established in June this year a group called the Central Five (C5). Slovakia’s experience with mass testing has become a reference point for, among others, its regional partners, including Austria.