Israel’s Policy in the Eastern Mediterranean

Energy Dimension

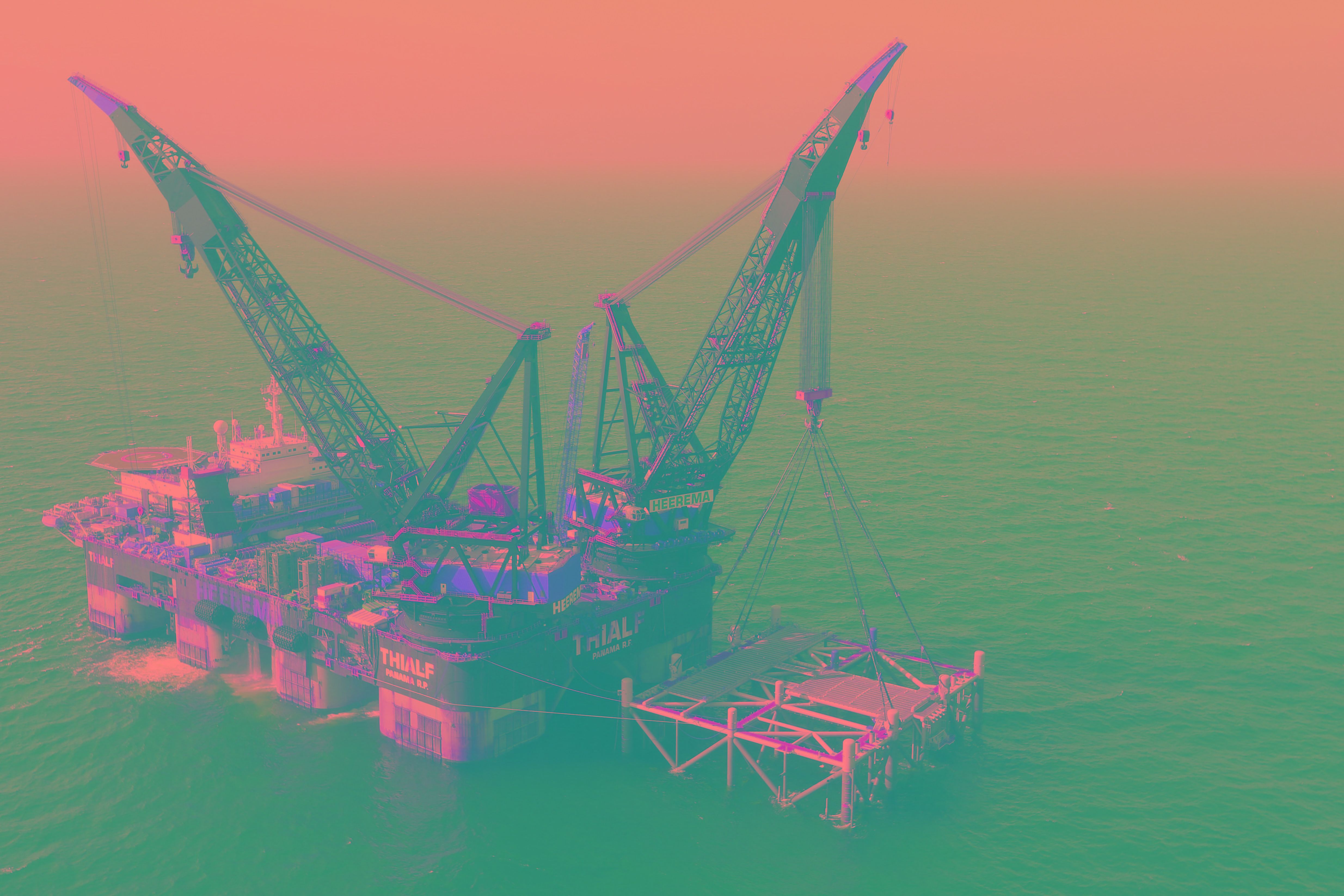

The beginning of extraction from new gas fields (primarily the Tamar and Leviathan fields discovered in 2009–2010, located approx. 80–130 km off Haifa) has opened new perspectives for Israeli foreign and economic policy. Proven reserves in Israeli territorial waters and its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) are about 400 billion m3 (bcm, sufficient to meet domestic consumption for about 40 years). The shareholders of the offshore fields are primarily Israeli companies and U.S. Noble Energy, the main operator.

Although gas consumption in Israel more than doubled in 2009–2017, the profitability of extraction is determined by future export. So far, contracts have been signed with neighbouring Jordan and Egypt while the contract with the Palestinian Authority (PA) hasn’t been finalized. Export to Jordan (with the total quantity of contracts at 48 bcm) began in 2015. Resolution of an arbitration dispute with Egypt (Israel has agreed to reduce compensation from Egypt for cancelling the previous agreement) clears the way for the implementation of a supply contract for 85,3 bcm. Transmission is expected to start at the end of 2019. The Egyptian direction (via the Ashkelon-Arish pipeline) is important because, apart from access to an absorbent market, it enables Israel to use Egyptian LNG infrastructure. The competitiveness of Israeli gas prices remains an open question, especially given high operating costs, the relatively low gas prices on global markets, and the discovery of significant deposits in Egypt itself.

Israel aims for EU countries to be the main gas recipients, so it has established cooperation with Cyprus and Greece under the so-called “Energy Triangle” (since 2011, six summits of the group have been held with the participation of prime ministers). The key project for this format is the construction of the Eastern Mediterranean pipeline (EastMed), which would allow gas transmission to Greece and further to Italy. The cost of the pipeline, which was labelled as a Project of Common Interest by the European Commission (EC), is estimated at about $7 billion and construction is expected to start in 2020 and take seven years. In addition, a gas route from Israel via Cyprus and Greece would connect with EU electricity infrastructure through the planned EuroAsia Interconnector. Complementing the tripartite format are strengthening relationships on other levels, primarily in security (e.g., training exercises, cybersecurity).

Israel has engaged in the institutionalisation of regional cooperation via the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), which was inaugurated in January and includes (besides Israel) Egypt, Greece, Cyprus, Jordan, Italy, and the PA. The EMGF, the goal of which is to build a regional gas market and coordinate policies in this area, is part of Israel’s aim to deepen relations with its immediate neighbourhood. The forum received clear support from the current U.S. administration (as well as for the “Energy Triangle”) and from EU institutions. It is also one of a few regional cooperation formats in which both Israel and the PA participate.

Regional conflicts remain an obstacle to the exploitation and use of this gas potential (including the lack of recognition of Israel by Lebanon and Syria). The Israeli-Egyptian blockade of the Gaza Strip remains a flashpoint. In May, escalation of the conflict with Hamas forced Israel to temporarily halt the work of gas rigs. In addition to the blockade, the ongoing conflict between Fatah and Hamas and the stagnation of the peace process are preventing the exploitation of Palestinian offshore gas resources. The investment announcements in this area were mentioned in the economic part of the U.S.-proposed peace plan, announced in June. The discovery of the deposits has also complicated the issue of the delimitation of the Israeli-Lebanese sea border. The disputed area is about 850 km2, which both sides consider to be part of their EEZ, while the U.S. serves as a mediator.

Security and the Turkish Factor

The war in Syria intensified the importance of the Eastern Mediterranean for Israeli security policy, in particular the participation of its major regional opponents—Iran and Hezbollah—and since 2015, also Russia. The Eastern Mediterranean is an operational area for the Israeli military (mainly the air force) against Iranian and pro-Iranian targets in Lebanon and Syria. The airstrikes are intended to prevent the transfer of advanced weaponry to Hezbollah and the strengthening of Iran’s military presence in the region. Although this conflict has not escalated, despite cyclical exacerbations, such as the exchange of fire on the Israeli-Lebanese border in September, it remains a major threat to the stability of the Eastern Mediterranean. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah has repeatedly threatened Israel (including in the context of the sea border dispute), pointing out that its gas rigs could be subject to attack. In turn, Israeli decision-makers made clear that the integration of Hezbollah into the Lebanese state apparatus exposes Lebanese infrastructure to counterattack. Russia’s military presence in Syria, primarily airspace control, further limits Israel’s operational freedom. Despite developed consultation mechanisms, the risk of incidents is high, such as the diplomatic crisis triggered in September 2018 by the downing of a Russian transport carrier by a Syrian anti-aircraft system after an Israeli air raid.

Persistent tensions in relations with Turkey remains a particular factor in regional Israeli. Their historically close relations collapsed in 2010 after Israel prevented an attempt to break the Gaza blockade by The Freedom Flotilla, a sea-based operation in which 10 Turkish citizens were killed. Official re-normalisation (which included Israeli compensation and the return of ambassadors) took place in 2016, yet relations have not improved. The main cause is the sharp criticism of Israeli policy towards the Palestinians by the Turkish authorities, especially by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Turkey provides diplomatic and financial support to both the PA and Hamas. In turn, Israel, striving to maintain a military qualitative advantage in the region, has lobbied for excluding Turkey from the F-35 programme. Although both countries still have strong economic ties and limited intelligence cooperation, Israel now perceives Turkey as a rival, not a partner. This influenced the change in gas transmission strategy for Israel. Although it would be cheaper for Israel to use the Turkish infrastructure and improve relations through energy cooperation, the current state of political hostility undermines such a scenario.

Conclusions

The permanent objectives of Israeli foreign policy—ensuring national security and deepening economic and political relations with the region—overlap in the Eastern Mediterranean. This makes Israel’s strategy independent from the changes in domestic policy, which contributes to the state’s credibility with potential partners. The main regional challenge for Israel remains the escalation in the conflict with Iran, especially if combined with Hezbollah’s involvement and military operations in Lebanon. At the same time, to secure its interests, primarily in gas exploitation, Israel requires support from foreign partners. This increases the role of not only the EU and the U.S. but also Russia (whose influence in the region has grown significantly) as mediators in de-escalating disputes with Turkey.

Cooperation on energy issues can serve as an impetus for improving Israel-EU relations, the deepening of which has mostly been dependent on progress in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. It is also in the EU’s interest (alongside the diversification of gas supplies) to further support the institutionalisation of regional cooperation because it is beneficial to the stability of the Union’s southern neighbourhood. However, attempts by Israel to use cooperation with European partners under the EMGF to soften EU positions cannot be ruled out, as was the case with relations with the Visegrad Group.

A new source of gas supply may be important for European projects such as the North-South Gas Corridor, supported by Central European countries and the EC. This is beneficial from the Polish point of view, as it provides an area of cooperation with Israel, even in the event of tensions at the bilateral level.