India and the Emerging Alliance of Democracies: High Stakes, Hard Choices

Towards an Alliance of Democracies

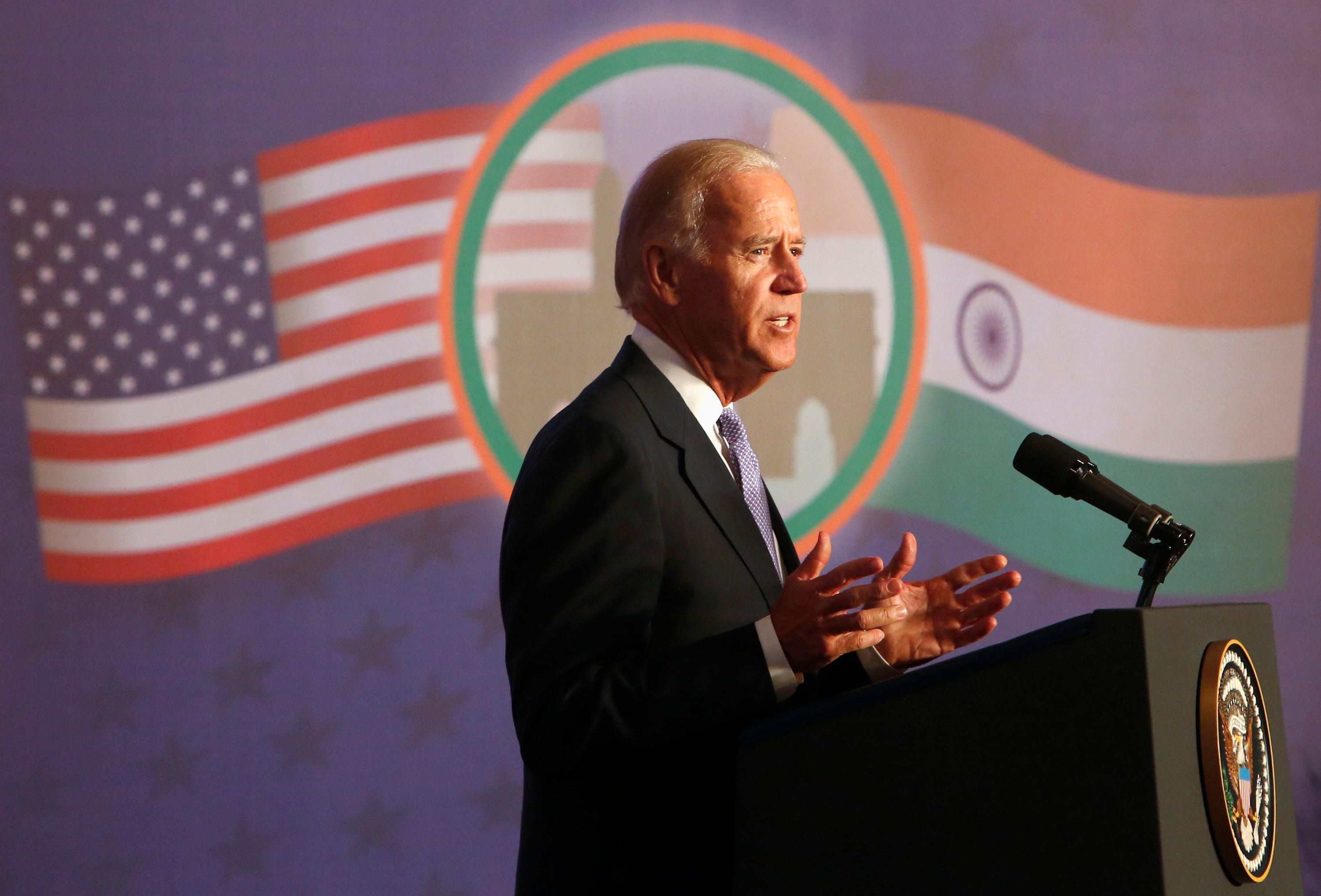

Biden’s victory in the U.S. presidential election raised the prospects that the country will return to its role as standard bearer and a global promoter of democracy and human rights. This would help halt the trend of a decline in democracy worldwide and renew the global liberal order.[1] As presidential candidate, Biden wrote in an article in spring 2020 that, after renewing democracy at home, he will “invite my fellow democratic leaders around the world to put strengthening democracy back on the global agenda.”[2] He further explained that during his first year in office, “the United States will organize and host a global Summit for Democracy to […] strengthen our democratic institutions, honestly confront nations that are backsliding, and forge a common agenda,” adding that it will look for “new country commitments in three areas: fighting corruption, defending against authoritarianism, and advancing human rights in their own nations and abroad.”[3]

| Though it is yet to be seen what form a global Summit for Democracy will take, the call has opened doors to closer cooperation between democracies against authoritarian regimes. |

Though it is yet to be seen what form, character, or specific goals this initiative will take and which countries will be invited to participate, the call has opened doors to closer cooperation between democracies against authoritarian regimes.[4] It resembles the benign Bill Clinton initiative of a Community of Democracies, formed in 2000, the more aggressive idea of a League of Democracies, proposed by presidential candidate John McCain back in 2007,[5] or the Alliance of Democracies championed recently by the former head of NATO, Anders Fogh Rasmussen.[6] Also, now former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who represented the Trump administration, sought to mobilise the “free world” in an ideological competition with authoritarian China, saying: “Maybe it’s time for a new grouping of like-minded nations, a new alliance of democracies.”[7]

Although the new administration will differ substantially from the previous one on many accounts, their approaches to closer cooperation between democracies seem to have a lot in common. Antony Blinken, new Secretary of State, imagined a new organisation: “call it a league of democracies or a democratic cooperative network” bringing together the U.S democratic allies from Europe and Asia “to forge a common strategic, economic and political vision.”[8] Some experts give more specific proposals of the new coalition of the world’s 10 major developed democracies, calling it the “D10”[9] or an “extended G7,” which would include also major countries from the developing world.[10] Other observers, however, challenge the latter as very difficult to be implemented and not the best to fit into the changed and complex geopolitical realities of 2020.[11] Whatever shape this coalition takes, the Biden administration is more likely to pursue values-based foreign policy and cooperate closer with democratic states.

Why India Matters

The success of any new initiative bringing together the world’s democracies depends to a large extent on including India in this grouping. It seems crucial for a number of reasons. India is not only the world’s largest democracy in terms of population but also the fifth-biggest economy and a major military power with nuclear capabilities. It provides democratic space and freedoms to more than 1.3 billion people (one-fifth of the world’s population) and holds the biggest free and fair elections with around 900 million voters—more than all Western democracies combined. It is a country increasingly critical of authoritarian China and growing ever closer to the U.S. and the EU.

India is one of only a few democracies in Asia functioning almost uninterruptedly since the Second World War. It has a pluralistic multiparty system, free and vibrant press, and an independent judiciary. All this in a developing country with a GDP per capita of less than $2,000, which according to the theory of modernisation should not be possible.[12] Despite serious setbacks and shortcomings, India is regarded by Freedom House as “free.”[13] India’s democratic flaws are not exceptional when looking at the established democracies in North America or Europe. Moreover, India’s experience with democracy holds particular value for other developing countries, where democracy is most lacking.

| Any alliance of democracies without India would only resemble a weaker version of itself from the Cold War days when the U.S. assumed the role of the leader of the “free world” in the ideological confrontation with the USSR. |

Any alliance of democracies without India would only resemble a weaker version of itself from the Cold War days when the U.S. assumed the role of the leader of the “free world” in the ideological confrontation with the USSR. It would lack legitimacy and credibility, seen only as a club of declining powers who simply want once again to use normative tools to protect and preserve their privileges in the international system. Yet, though the value of India in any significant grouping of democracy is self-evident, it is not that clear whether it would be interested in joining.

Opportunities for India

Any global initiative that highlights the role of democratic form of governance is good news for India. It felt for a long time that it does not get enough credit for maintaining democracy while the West preferred to do business with undemocratic China. One can hear complaints even today that while India struggles to lift millions of people out of poverty and develop the country in conditions of respect for human rights, pluralism and the rule of law, China grew without paying the same due attention to democratic norms.[14] If the situation is to be changed soon, it could bring important benefits to India.

First, it would allow the country to raise its voice on global issues and help it realise its major power aspirations. India has played the democratic card more willingly in the 21st century to win favours from Western democracies and make its arguments better heard on international forums. In the last few years, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Indian diplomats presented India as a “leading power” and a force for good in the world. In the absence of U.S. global leadership under Trump, some influential Indian thinkers claimed even that India is “the only one legitimate heir to the global liberal order of any consequence”[15] and is crucial to uphold the rules-based international order.[16] The global coalition of democracies would further raise India’s international standing and boost its soft power. The country may hope that together with fellow democracies, it may shape international rules and norms in new areas, such as cybersecurity, AI, and data privacy.

| Building partnerships based on shared values would allow India to strengthen ties with Western partners, and the U.S. in particular. |

Second, building partnerships based on shared values would allow India to strengthen ties with Western partners, and the U.S. in particular. Though they are often seen in New Delhi as declining powers, they still have valuable assets that India badly needs—capital, technologies, and influence in global decision-making bodies. Hence, they are crucial for India’s modernisation, socio-economic development, and security interests in Indo-Pacific. Through the “Self-reliant India” campaign, Modi hopes that mutual trust and common values will allow it to attract some Western investments away from China so India can play a larger role in global supply chains. Though this normative and ideological bond played a less important role in U.S.-India relations under Trump, the Biden administration may again put it at the forefront. Most importantly, it would allow India to distinguish itself positively from China, its main geopolitical rival.

Third and probably the most important, its democracy may help India in the geostrategic competition with its biggest neighbour. Though it has long refrained from open criticism of China for the sake of its own economic and strategic interests, the situation changed dramatically in 2020. Growing criticism of China by the Trump administration, China’s reclusiveness in handling COVID-19, and the border skirmishes and standoff in Ladakh in June 2020 made India stand up to its neighbour more openly. Indian strategists became more vocal in recognising China as an “enemy” and a major “threat,” and started highlighting ideological differences more actively.

Some Indian analysts called for India to drop its Cold War “non-alignment” thinking and suggested a new interpretation of “strategic autonomy” that looks for strong security partnerships with like-minded partners in its rivalry with authoritarian China.[17] Shedding old assumptions led India already to reengage in the Quad, a security dialogue of four fellow democracies in Indo-Pacific: the U.S., India, Japan, and Australia, with its second foreign ministers meeting in Tokyo in September 2020 and its first joint naval exercises (Malabar) in November 2020. India also joined the Franco-German initiative Alliance for Multilateralism in 2019. The idea of a coalition of democracies to jointly counter the growing influence of undemocratic China seems to fit well into this more assertive policy of balancing against China and the general trend of changing India’s grand strategy.

India’s Hesitations

Yet, the renewed focus on values in U.S. foreign policy and proposal of a forum of democracies bears several risks for India and may not be that attractive for at least three reasons.

First, India, under the strong leadership of Prime Minister Modi, who champions democracy globally, is actually facing internally the strongest democratic backsliding in decades. More nationalistic rhetoric, harsh treatment of religious minorities, circumscribing media freedom, controversial national citizenship laws, and restrictions on the operations of foreign NGOs invite growing criticism from human rights organisations and international media. Closing of the Amnesty International office in India in Autumn 2020, like Russia did years ago, is just the most recent example of the shrinking freedom in the country.[18] The most recent report by Freedom House (2019) recorded the highest decline in democracy in India among the 25 largest democracies.

India may find itself under more scrutiny on democratic standards from the new U.S. administration, which many observers expect,[19] and more importantly, domestic problems limit the usefulness of the democratic card in its foreign policy. If India wants to join the West in championing human rights in other countries, it invites more interference in its own domestic affairs. A recent diplomatic spat with Canada over comments on farmers’ protests in India reveals that Indian politicians are not ready for that yet.[20] Moreover, it may create problems not only for India but also for its foreign partners. For example, as they become more vocal in criticising China for human rights violations of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang, they may expect more questions about India’s treatment of Kashmiri Muslims.[21] Freedom House warns that while India wants to be a more trusted partner of liberal democracies than China, “the Indian government’s alarming departures from democratic norms under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) could blur the values-based distinction between Beijing and New Delhi.”[22]

| Though India itself did practice some forms of democracy assistance in its foreign policy and was no stranger to foreign interventions for humanitarian reasons, its approach differed substantially from that of the EU or the U.S. |

Second, it is not clear yet whether the ongoing shift in Indian foreign strategy also will bring a change in its position on democracy promotion. India has been traditionally critical of the Western approach and there was no break from the past during Modi’s first term.[23] In general, India used to see this policy as interference in the internal affairs of other countries and a breach of their sovereignty—the core principle of its foreign policy. In fact, India’s views on democracy promotion were more in common with other BRICS nations and many developing countries than with the West. Memories of past abuses of democracy promotion, including by the George W. Bush administration, are still vivid among many. Foreign interventions in the name of human rights or the Responsibility to Protect principle were seen as instruments of “regime change” that stirred chaos in international relations.[24]

Though India itself did practice some forms of democracy assistance in its foreign policy and was no stranger to foreign interventions for humanitarian reasons (i.e., Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971), its approach differed substantially from that of the EU or the U.S.[25] Though it joined the Community of Democracies in 2000 and the UN Democracy Fund in 2005 to please the U.S., it has remained more or less a passive member. Moreover, India sees the “democratic deficit” in international relations somehow differently than most of its Western partners. While they tend to focus on individual human rights and democratic governance at the country level, India elevates it to the international stage, seeking global governance that is more democratic and representative (in practice to give more voice to developing countries, including itself).

Third, India would face a challenge in reconciling the joining of a bloc of democracies with its traditional friendship with several undemocratic states for pragmatic considerations. Though India’s historical ties with Russia have been weakening in recent years, it is still an important source of armaments and military and nuclear technologies. Prime Minister Modi assured Vladimir Putin in July 2014: “every child in India knows that Russia is the best friend of India.”[26] India is thus more vocal in supporting international law and rules-based order in, for example, the South China Sea, while silent regarding Russia’s annexation of Crimea in clear violation of the sovereignty of an independent state—Ukraine.

As India’s ties with Russia are unique for a number of historical and strategic reasons, it is not the only undemocratic state with which India shares strong ties. It did not criticize the military junta in Myanmar before its 2011 transition, nor did it join the West in its recent condemnation of Aung San Suu Kyi for the army’s persecution of Rohingya in 2017. India needs good relations with its eastern neighbour to stabilise its northeast region and boost connectivity to ASEAN. India did not take the moral high ground when dealing with the authoritarian government in Iran, as that country is an important source of energy supplies and a strategic partner in the larger Middle East. Human rights considerations have not stopped the Indian government from developing an even stronger partnership with the hardly democratic Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies in recent years. One can go on with more examples.

This situation shows that strategic calculations and compulsions create inherent tensions in any future Indian strategic approach to democracy promotion. While on the one hand India would like to use the democratic argument against China, it is unlikely to apply it to relations with Russia or other friendly authoritarian regimes. Thus, it would be tempted to use the selective approach to democracy promotion—hypocritical given it used to heavily criticise Western powers for doing just that.

Conclusions: To Lead by Example

| The invitation of Narendra Modi to the Summit of Democracies brings certain risks to the credibility of Biden’s initiative, but any such group without India is even riskier. |

India’s position on democracy is full of nuance, tensions, and ambiguities. And that can be fully understood considering its difficult neighbourhood, low level of development, and magnitude of internal challenges and external threats. It is not very different from other Western countries in this regard. Yet, India is an indispensable element of any global initiative on democracy. Despite its democratic shortcomings, or rather because of them, India has a lot to offer other developing and emerging democracies as it better fits their development challenges. Though the invitation of Narendra Modi to the Summit of Democracies brings certain risks to the credibility of Biden’s initiative,[27] any such group without India is even riskier. Leaving it out could not only hurt U.S.-India relations but more importantly, dent the legitimacy of this global forum.

If India is invited to the new democratic forum, it will most likely agree to join, primarily to maintain the momentum in bilateral relations with the U.S. and balance against China. Joining offers in the end more opportunities to India than risks (e.g., Chinese provocations). Though it may expect tough discussions about its domestic policies, India has much more to gain. Yet, to have the country as a meaningful and active member of the new forum of democracies, some of its concerns about the forum also must be taken into account.

First, it would need to be a rather loose coalition of like-minded countries sharing similar values and concerns than a formal alliance. Hence, it should not be presented as an exclusive club, directed against any particular enemy (China), but rather an inclusive platform open to all respecting international rules and laws and focused on a positive agenda.

Second, the new initiative must not limit itself to discussing democracy at the national level but strive for reforms towards a more democratic and effective international system. The democratic coalition would need to propose new initiatives and revive discussions on reform of global institutions to make them more effective, representative, and fit for the 21st century. Proposing a joint draft text of UN reform, including of the Security Council with a place for major democracies like India, would be proof that democracies can make a difference.

Third, it would need to respect the diversity of democratic systems and different approaches to democracy assistance. The best the U.S. and India could do for the promotion of democracy is to lead by example and prove the resilience of democratic systems, which have inbuilt mechanisms of self-correction. This would require withdrawing from undemocratic policies and attacks on democratic institutions or principles, not only in the U.S. but also in India and elsewhere. It may turn out that the most difficult part of it for Prime Minister Modi is the need to rebuild India’s image as a tolerant and democratic country.

Fourth, India would look for practical deliverables of cooperation—new mechanisms and funds to strengthen the resilience of democratic societies against global threats such as climate change, terrorism, protectionism, or disinformation. It would like to cooperate with other democracies to renew existing institutions (e.g. WHO, WTO) while shaping new norms in ungoverned domains, such as cyber, connectivity, or space.

| For the European Union, the active participation of India in this forum would be an advantage. |

For the European Union, which on the one hand has already signalled its readiness to “play a full part in the Summit for Democracy proposed by President-elect Biden,”[28] and, on the other hand, plans to broaden cooperation with like-minded democracies, the active participation of India in this forum would be an advantage. The EU can work with the U.S. to accommodate some of India’s concerns and plan joint initiatives, e.g., on climate change or development assistance. This would help to strengthen the EU-India partnership and realise the full potential of cooperation between the three biggest democracies.

[1] The liberal international order or rules-based liberal order refers here to the U.S.-led western order, established after 1945 and expanded globally in the post-Cold War period, and which is based on international law, an open economy, multilateral institutions, and organised around liberal principles. See, e.g.: J. Ikenberry, “The Future of the Liberal World Order: Internationalism after America,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2011, pp. 56-68.

[2] J. R. Biden, Jr., “Why America Must Lead Again. Rescuing U.S. Foreign Policy After Trump,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2020.

[3] Ibidem

[4] A. Vindman, “The United States Must Marshal the ‘Free World’. Together, Democracies Can Counter the Authoritarian Threat,” Foreign Affairs, 7 December 2020.

[5] J. McCain, “An Enduring Peace Built on Freedom. Securing America's Future,” Foreign Affairs, November/December 2007.

[6] Rasmussen formed the Alliance of Democracies Foundation in 2017 as a non-profit organisation dedicated to the advancement of democracy and free markets across the globe, and with the Copenhagen Democracy Summit as its flagship initiative. https://www.allianceofdemocracies.org/.

[7] M. R. Pompeo, “Communist China and the Free World’s Future,” Speech at The Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, Yorba Linda, California, 23 July 2020.

[8] A. Blinken, R. Kagan, “America First is only making the world worse. Here’s a better approach,” Washington Post, 1 January 2019.

[9] The Atlantic Council initiated the D10 Strategy Forum in 2014 to bring together top policy-planning officials and strategy experts from 10 leading democracies: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States, plus the European Union. See: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/programs/scowcroft-center-for-strategy-and-security/global-strategy-initiative/democratic-order-initiative/d-10-strategy-forum/.

[10] M.H. Fuchs, “How To Bring the World’s Democracies Together. A Global Summit of Democracies,” Centre for American Progress, November 2020.

[11] A.D. Miller, R. Sokolsky, “An ‘alliance of democracies’ sounds good. It won’t solve the world’s problems,” Washington Post, 13 August 2020; J. Goldgeier, B. W. Jentleson, “A Democracy Summit Is Not What the Doctor Ordered. America, Heal Thyself,” Foreign Affairs, 14 December 2020; S. Islam, “Biden’s ‘summit of democracies’ won’t work,” Politico, 8 December 2020.

[12] For instance, Adam Przeworski shows that democracies are at high risk of collapsing until they reach an income level above $6,000 per capita. See: A. Przeworski, “Democracy as an Equilibrium,” Choice 123, no. 3/4, 2005, pp. 253–273.

[13] “Freedom in the World 2020. A Leaderless Struggle for Democracy,” Freedom House, Washington 2020.

[14] “We are too much of a democracy … though reform hard: Niti Aayog Chief Amitabh Kant’s wisdom,” The Indian Express, 9 December 2020.

[15] S. Saran, “India’s Role in a Liberal Post-Western World,” The International Spectator, vol. 53, no. 1, 2018, pp. 92–108.

[16] S. Tharoor, S. Saran, The New World Disorder and the Indian Imperative, Aleph Book Company, New Delhi, 2020.

[17] R.C. Mohan, “India’s strategic autonomy is about coping with Beijing’s challenge to its territorial integrity, sovereignty,” The Indian Express, 25 August 2020.

[18] H. Ellis-Petersen, B. Doherty, “Amnesty to halt work in India due to government ‘witch-hunt’,” The Guardian, 29 September 2020.

[19] M. Kugelman, “What a President Biden would mean for India and world,” India Today, 7 November 2020.

[20] “India formally protests to Canada over Trudeau remarks on farm protests,” Reuters, 4 December 2020.

[21] R. McGregor, “Fareed Zakaria on Australia’s ‘opportunity’ between the U.S. and China,” The Interpreter, 27 November 2020.

[22] “Freedom in the World 2020 …,” op. cit., p. 2.

[23] I. Hall, “Not Promoting, Not Exporting: India’s Democracy Assistance,” Rising Powers Quarterly, vol. 2, iss. 3, 2017, pp. 81–97

[24] See: H. Singh Puri, Perilous Interventions: The Security Council and the Politics of Chaos, HarperCollins, 2016.

[25] P. Kugiel, “The European Union and India: Partners in Democracy Promotion?,” PISM Policy Paper, no. 25, February 2012.

[26] R.C. Mohan, “India, Russia, here and now,” The Indian Express, 10 December 2014.

[27] E. Luce, “Biden’s dilemma on global democracy,” Financial Times, 19 November 2020.

[28] European Commission, “EU-U.S.: A new transatlantic agenda for global change,” press release, Brussels, 2 December 2020.